The Mentally Ill & Criminal Justice in China: An Interview with Prof. GUO Zhiyuan

A true test of any criminal justice system is how it treats its most vulnerable and perhaps one of the most vulnerable groups in any society is the mentally ill. Shunned by many in the world and often incapable of asserting their rights when questioned by police, the mentally ill are often left unprotected. In its almost 250-year existence, the United States has come a long way in protecting the rights of the mentally ill but not without a struggle. While the insanity defense and competency to stand trial have long been a part of Anglo-American jurisprudence, the requisite procedures to evaluate mental illness are of more recent provenance.

A true test of any criminal justice system is how it treats its most vulnerable and perhaps one of the most vulnerable groups in any society is the mentally ill. Shunned by many in the world and often incapable of asserting their rights when questioned by police, the mentally ill are often left unprotected. In its almost 250-year existence, the United States has come a long way in protecting the rights of the mentally ill but not without a struggle. While the insanity defense and competency to stand trial have long been a part of Anglo-American jurisprudence, the requisite procedures to evaluate mental illness are of more recent provenance.

Given our difficulty, how does country like China, with a criminal justice system that has only been around for 32 years, handle mentally ill suspects and defendants? Prof. GUO Zhiyuan (pronounced Gwo Zhir-yooan), Associate Professor of Law at the China University of Political Science and Law, has answered that question in her recent article “Approaching Visible Justice: Procedural Safeguards for Mental Examinations in China’s Capital Cases (Hastings Int’l. and Comp. L. Rev., Winter 2009).

With the first candid examination (at least in English) of the interplay between the Chinese Criminal Law and the Chinese Criminal Procedure Law, Prof. Guo shows us that while the law ostensibly protects the mentally ill, there is a lack of procedural protections. If the defense attorney doesn’t have the right to call for a mental examination of his or her client, what good is an insanity defense? Prof. Guo examines these issues and offers potential reforms in Approaching Visible Justice. From our own experience, protecting the mentally ill is not an easy task, but with scholars like Prof. Guo working on this issue, there is the possibility that China is not far from offering similar protections. Below is an interview with Prof. Guo discussing her recent article and the plight of the mentally ill in the Chinese criminal justice system

*********************************************************************************************************

EL: Does the Chinese criminal law have special protections for the mentally ill? Is there an insanity defense like there is in the U.S.? In what other ways does mental illness come into play under China’s criminal law?

GZY: Yes, Chinese criminal law does have special protections for the mentally ill. Article 18 of the Criminal Law of the PRC [People’s Republic of China]states:

“If a mental patient causes harmful consequences at a time when he is unable to recognize or control his own conduct, upon verification and confirmation through legal procedure, he shall not bear criminal responsibility. . . . If a mental patient who has not completely lost the ability of recognizing or controlling his own conduct commits a crime, he shall bear criminal responsibility; however, he may be given a lighter or mitigated punishment.”

Although defendants with mental illness do not bear criminal responsibility, Article 18 of the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China stipulates that:

“his family members or guardian shall be ordered to keep him under strict watch and control and arrange for his medical treatment. When necessary, the government may compel him to receive medical treatment.”

Article 18 also emphasizes:

“[a]ny person whose mental illness is of an intermittent nature shall bear criminal responsibility if he commits a crime when he is in a normal mental state.”

This is the same as in the American model, where the mental status at the time of crime is relevant in determining criminal responsibility.

EL: How does a defendant or his lawyer, make a claim that he is mentally ill and thus subject to the laws protections? Does the defendant or his lawyer call for a mental examination? Who pays for the mental examination?

EL: How does a defendant or his lawyer, make a claim that he is mentally ill and thus subject to the laws protections? Does the defendant or his lawyer call for a mental examination? Who pays for the mental examination?

GZY: In China, only the police, the prosecution or the court can decide to conduct a mental examination. Neither the defendant nor his lawyer can initiate an evaluation; they also cannot apply to the judicial agencies for one; they can only apply for supplementary evaluations or re-evaluations after an officially-initiated examination has produced results. To my knowledge, both the officially-initiated mental examinations and the supplementary evaluations are conducted at the State’s expense, but when the defendant or his lawyer successfully initiates a re-evaluation, they retain mental health experts at their own expense.

EL: If you could redesign China’s criminal law and criminal procedure law, what would you change so that China best protects the mentally ill when they interact with the criminal justice system? In other words, what would the ideal system look like?

GZY: I don’t see anything inappropriate in the provision in China’s Criminal Law, but it’s necessary to reform the Criminal Procedure Law of China. To be exact, procedural safeguards should be added to the current Criminal Procedure Law in order to put Article 18 of China’s Criminal Law into practice. It seems to me that the ideal system should, at the very least, adopt the following seven proposed reforms: First, for all capital cases, a mandatory pretrial examination of defendants’ mental status should be required at the State’s expense. Second, the defense should be entitled to retain its own mental heath professionals who are allowed to witness and participate in this proposed mandatory mental examination or any other mental examinations initiated by the prosecution. Third, the defense’s right to initiate its own examination should be granted and respected. This would be the most important change if it does occur. Fourth, both parties should have a right — not just the defense — to confront the opposing side’s psychiatrist or other mental health examiner; this right should be guaranteed. Fifth, the indigent defendant should be entitled to psychiatric assistance at the State expense; this would ensure equal treatment among defendants with different financial means. Sixth, to address the problem of conflicting expert testimony, an additional impartial psychiatrist should be appointed by the court to perform another independent assessment. This would aid the court in determining the mental condition of the defendant. Finally, effective assistance of counsel should be emphasized in those capital cases involving mentally disabled defendants.

EL: In China, sometimes a lawyer is held liable for the acts of his client (e.g. when a client perjures himself his attorney could be held liable). Does a defense lawyer get into trouble if his client pleads “not guilty for reasons of insanity” and is found not to be insane? Will the lawyer be censured?

GZY: Although it’s very easy for a defense lawyer to get into trouble if his client withdraws a confession he made to the police, cases are very rare in which a lawyer gets into trouble because his client was found sane after pleading “not guilty for reasons of insanity.”

EL: In the U.S., mentally ill defendants don’t often receive the public’s sympathy. But in your article, you discuss the

case of Yang Jia, a man who stormed a Shanghai police station and killed six police officers after he had been harassed by the police. The Chinese public was largely sympathetic toward him – do you think this was because people felt sorry for him because he was mentally ill?

GZY: No. Although many thought that Yang Jia was insane, whether he was actually mentally ill or not would have depended upon further serious assessment by qualified and impartial professionals. In Yang Jia’s case, the Chinese public was largely sympathetic towards him for the following reasons. First, with the public’s increasing awareness of their legal rights, police misconduct – which, of course, is not a uniquely Chinese problem – has met with unprecedented condemnation, and the call for judicial fairness has become more and more intense in these cases. The motive behind Yang Jia’s attack –avenging past police misconduct – played directly to this sentiment. Second, there were a number of procedural flaws in Yang Jia’s case, such as lack of transparency, conflict of interest, and serious problems regarding the mental examinations. The general public just seized on Yang Jia’s case as an opportunity to express their anger at police violence and to voice their demands for a more fair criminal justice system.

EL: Do you think there is increasing sympathy toward mentally ill defendants in China? Are attitudes changing? How are attitudes changing?

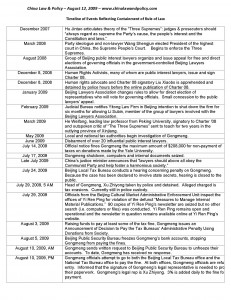

GZY: Yes, more and more attention is paid to mentally ill defendants in China, especially after a series of relevant high-profile cases such as Qiu Xinghua’s, Yang Jia’s, and Akmal Shaikh’s cases. The general public has being changing their indifferent attitudes towards mentally ill offenders; more and more people have realized it’s essential to establish a fair judicial system to prevent the state from punishing the mentally ill. For this transformation, open information has played an important role.

EL: Thank you Prof. Guo for your time and your insights on a very important issue in every criminal justice system.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email