Do Human Rights Restrictions At Home Undermine China’s Role At the UN?

By Sara L.M. Davis*

This post is co-published on Meg Davis Consulting

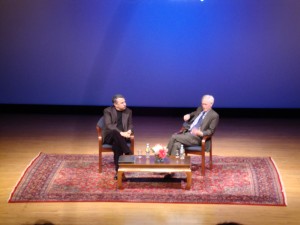

A few weeks ago – it feels like longer, given the COVID-19 crisis – I sat in a studio at the UN in Geneva with BBC journalist Imogen Foulkes, Sarah Brooks (ISHR) and Daniel Warner for a great chat about China at the United Nations. You can hear the conversation here .

Foulkes asked the panel: After years of marginalization, China is exercising growing influence at the UN, increasing its UN spending and heading five UN agencies. But what does China’s commitment to multilateralism mean in practice?

The panelists disagreed about some things, but we agreed overall that China still seems to be finding its way at the UN. In speaking with friends inside UN agencies and serving on governance boards, China’s presence at the UN appears hesitant; Chinese representatives are formal, careful with protocol, and reluctant to speak off the script without authorization from Beijing. This impedes their ability to cut deals, influence others and build relationships in the UN that are key to exercising power. Such hesitancy may link to China’s restrictive human rights climate at home.

In 2017, Chinese leader Xi Jinping gave a series of major speeches in defense of global governance, such as this one at the World Economic Forum. In line with his report to the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi pledged that China would show greater leadership in world affairs, and spoke of a shared destiny for humanity. Since then, Chinese directors have taken the helm at four UN agencies, and a Chinese delegation also chairs the Programme Coordinating Board of UNAIDS.

However, in my experience working in global health, in contrast to some other countries – such as India, France, the US or UK, for example – there are still relatively few Chinese technical experts working in the international organizations, academic institutes, private foundations and think-tanks that develop and advise on UN policy. China is rich in experts on development, social science, health, environment, law and economics. The fact that few of them staff technical roles at global health institutions means those policies rarely draw on research or policy experience from the world’s largest country.

Similarly, while NGOs play an important role in the UN – they share policy expertise and real-life experience, advocate for women and marginalized groups, and work together across national borders to promote accountability – there are very few Chinese NGOs engaged in UN policy discussions in Geneva. They are not to be seen organizing or speaking on side events, signing onto international coalitions, or speaking up in media discussions – and the one I participated in was an unfortunate case in point. Foulkes said she made an effort to recruit a Chinese panelist (I also suggested a couple of names), but everyone politely declined. Our podcast discussion would have been enriched by a Chinese perspective – we might not have agreed about everything, but it would have been a richer conversation.

The end result of these absences is that no one is sure what China’s agenda is at the UN, and everyone is walking on eggshells: UN agencies are afraid to say the wrong thing and risk angering a famously thin-skinned government; WHO has lavished praise on China’s COVID19 response, in part because it needs to win China’s cooperation in the global response. Similarly, Chinese representatives and academics are probably also afraid of getting into trouble at home, and are sticking closely to the approved script, or choosing to stay silent.

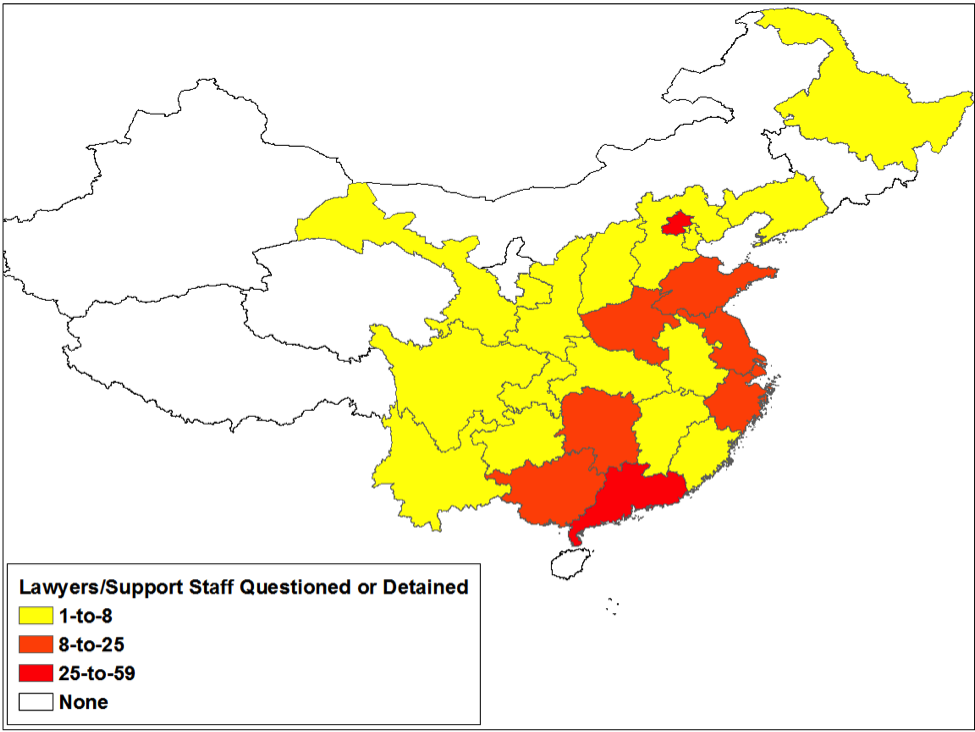

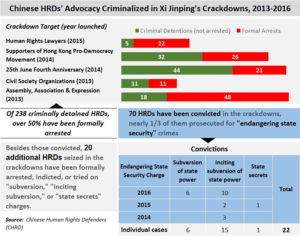

The reticence of China’s representatives in Geneva is likely a reflection of the chilling effect created at home by sweeping attacks on human rights groups, civil society groups, public interest lawyers, civil society leaders, other critics, and even family members of those critics under Xi Jingping’s regime. Fear of making a misstep may actually inhibit the kind of warm, informal personal relationships, off-the-cuff media remarks, deal-making, and intel-swapping over dinners, at bars and around the coffee urn that are usually – in normal days, when we can speak from closer than six feet apart – the currency in a political town like Geneva.

Weak and restricted civil society at home also deprives Chinese authorities of a crucial stream of intelligence and insight that would only advance their multilateral strategy. Civil society activists from many other prominent countries, including global North and global South, are actively engaged in UN advisory groups, civil society forums, coalitions and workshops in Geneva. As a result, these activists develop personal relationships with technical experts and managers of international organizations, as well as with diplomats from other countries, and get insights into how those agencies work in practice and what everyone’s agendas are. Activists then use that intel to inform and advise their own governments, pushing for policies while creating a feedback loop. But Chinese civil society leaders aren’t in those coalitions and advisory groups, for the most part, because they are not allowed to come to Geneva to speak critically about their own countries’ policies, and hobknob freely with their peers, the way an activist from Africa, Europe, Southeast Asia or Latin America might do. Chinese activists who speak up in Geneva, like Cao Shunli (who tried to come to Geneva for a human rights meeting, and later died in detention) face the risk of serious repercussions.

In other words, human rights restrictions at home are undermining the multilateralism China has promoted as a national policy. Leadership at the UN is not just about having the title at the head of international organizations: leadership is also exercised through academics, NGOs, lawyers and others who are part of the UN community, who feel confident and free to express their opinions, and make experience- and evidence-based policy recommendations. Until China has a strong and free civil society, the country may have a difficult time fulfilling its ambitions of global leadership.

*Sara L.M. Davis (known as Meg) is an anthropologist and human rights advocate. She is Special Advisor on Strategy and Partnerships at the Graduate Institute’s Global Health Centre and teaches at the Geneva Centre for Education and Research in Humanitarian Action (CERAH). A former China researcher for Human Rights Watch and founding Executive director of Asia Catalyst, Davis is fluent in Mandarin. Her forthcoming book, The Uncounted: Politics of Data in Global Health, is set to be published in June 2020

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email