China’s Peaceful Rise? The Fate of Lawyer Liu Yao

Since 2004, it has been illegal to build golf courses in China. Not only do they suck up a tremendous amount of water, but all too often local officials unlawfully appropriate farmers’ land for these golf courses. In 2015, President Xi Jinping focused his anti-corruption campaign on the sport, forbidding Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials from playing the game. But even with these prohibitions, golf still reins. Since 2004, over 400 new golf courses have been illegally built.

Since 2004, it has been illegal to build golf courses in China. Not only do they suck up a tremendous amount of water, but all too often local officials unlawfully appropriate farmers’ land for these golf courses. In 2015, President Xi Jinping focused his anti-corruption campaign on the sport, forbidding Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials from playing the game. But even with these prohibitions, golf still reins. Since 2004, over 400 new golf courses have been illegally built.

Thus, one would think that the Chinese government would welcome a local tip that an official was appropriating village land to sell to a developer to build a golf course. But that is not how the Chinese government responded when, in August 2015, Guangdong attorney Liu Yao reported precisely that. Instead, Liu Yao now sits in a jail cell, serving a 20 year sentence on what most believe are trumped-up charges in retaliation for his whistle-blowing.

Like many Chinese human rights lawyers, Liu Yao is not a stranger to the inside of a Chinese prison. In 2008, Liu was given a four year sentence for leading a demonstration of farmers who had not been properly compensated when government officials took their land. His sentence was decreased to 18 months after the Shenzhen Lawyers Association began a campaign to expose the sham that was his conviction.

But as in every society, land has value and the powerful will seek to unlawfully strip the poor of their land rights, enriching themselves in the process. For China, that struggle is happening in the rural villages. And that is what makes Liu, an effective advocate for these rural poor, a danger to the powerful.

Liu Yao awaiting his verdict

But Liu is more than just an advocate. He is one also of them, deepening his clients’ faith and trust in him. As Tom Mitchell reported back in 2009, Liu himself is the son of farmers, teaching himself the law after witnessing injustices against his family and feeling powerless to do anything about it. He knows the value of land to farmers and since passing the bar exam in 2003, has successfully helped farmers in his home province of Guangdong to fight to keep their land or, at the very least, for the market value of what they are forced to give up.

So when He Zhongyou, the Party Secretary of Heyuan City in rural Guangdong, appropriated thousands of farming fields to sell to a company to build an “ecotourist site”, Liu, whose 2008 conviction resulted in his disbarment, did what he could: he filed a complaint about He Zhongyou to the CCP’s Commission for Discipline Inspection in Guangdong. Make no mistake, He Zhongyou’s ecotourism development was not a secret to the central government; the local state-run media had already celebrated He Zhongyou’s development. But what Liu highlighted was the fact that the ecotourist site was to also include an illegal golf course, something not reported by the press. And Liu did not just submit the complaint. A few days later, on August 22, 2015, he also published it on his blog for all to read.

On December 26, 2015, while meeting with a colleague, Liu Yao was grabbed by a number of men, thrown into an unmarked minivan and taken away according to an article that appeared in the Southern Metropolis Daily.

For over six months, Liu was held incommunicado, under the now infamous and well-abused legal procedure of “residential surveillance at a designated location” (RSDL). Under Article 73 of the Criminal Procedure Law (CPL), RSDL is permitted when the individual is being investigated for national security crimes; national security also permits the police to deny access to lawyers and family members (CPL, Art. 37; see also RSDL Monitor for more on the abuse of RSDL on human rights defenders). The “evidence” the police used to claim that it was investigating Liu Yao for national security crimes, was a picture of Liu with two well-known Western China law experts, Professors Jerome Cohen and Eva Pils. Because of that picture, the police claimed that they were investigating Liu for “providing state secrets to foreigners.”

Liu Yao and his wife, Lai Wei’E

Ultimately, the police’s national security investigation went nowhere except for the very useful fact that it provided a fig leaf of legality to deny Liu access to his own lawyer. On June 23, 2016, Liu was officially charged with extortion (Art. 274 of the Criminal Law (CL)), fraud (CL, Art.192,) , and trafficking in children (CL, Art. 240). The extortion and fraud claims related to Liu’s work in achieving beneficial settlements from some of the local industries for their illegal appropriation of his clients’ land. The trafficking charge was a result of his and his wife’s adoption of a baby from an unwed mother who already had three other children. But in addition to Liu, four local farmers were also charged as well as Liu’s own son. Liu’s wife, Lai Wei’E was also held for a year, allegedly while the police were investigating the legality of the adoption.

With a closed door trial, lack of access to a lawyer, and the fact that Liu was exposing the local government’s most important revenue-generating strategy – illegal land grabs – a judgment of guilty on all charges was all but certain. And on April 24, 2017, the Heyuan City Intermediate People’s Court found Liu Yao guilty, sentencing him to 20 years and a fine of 1.4 million RMB ($221,000). Liu’s son was given four years and three months for helping his father post materials online with the three farmers receiving sentences ranging from four years to nine and half years.

He Zhongyou

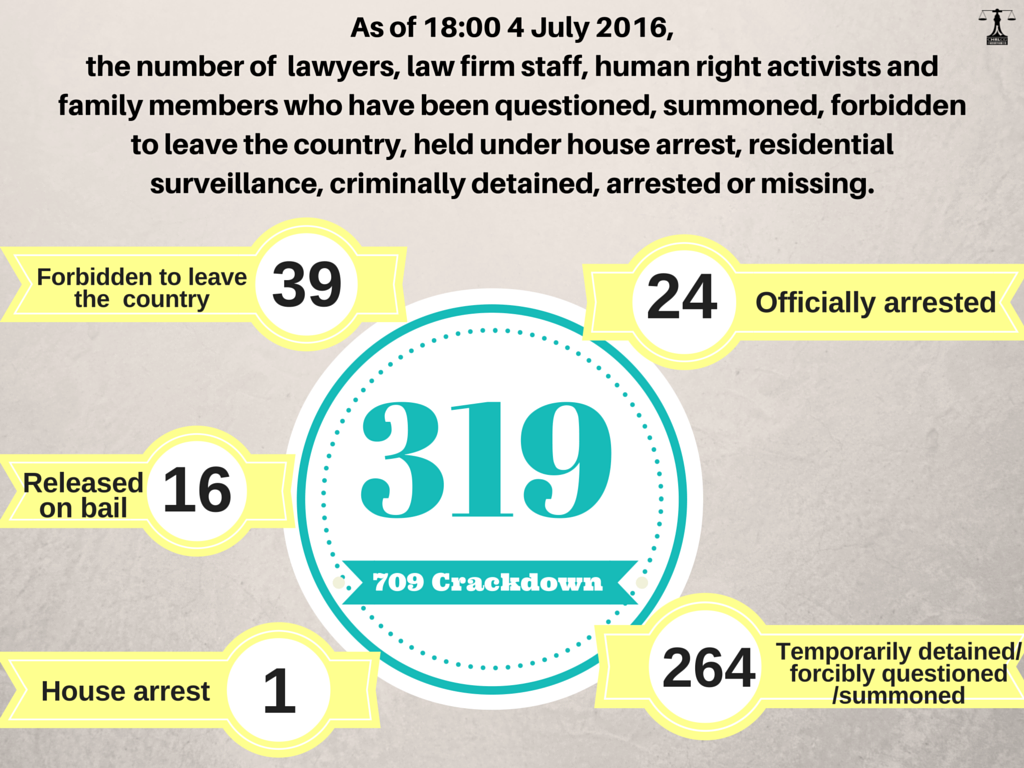

Even with the Chinese government crackdown on human rights lawyers that began in earnest in July 2015, Liu’s 20 year sentence is harsh. It is almost triple that which was given to the “ringleaders” of China’s human rights lawyers. Such a harsh sentence likely shows the continued importance to the Chinese government of being able to take farmers’ land without proper compensation. Even representing Falun Gong participants, petitioners, other rights activists is not as threatening to the government as representing those who challenge an important revenue source to local officials.

And what happened to He Zhongyou after Liu Yao exposed his land grab to build a golf course? He has had a series of promotions. In January 2016, as Liu languished in detention, He Zhongyou became the vice-governor of Guangdong Province, an influential position in one of China’s wealthiest provinces. In May 2017, after Liu Yao received his 20 year sentence, He Zhongyou was again promoted to the powerful position of Secretary of the CPP’s Political and Legal Affairs Commission for Guangdong.

From the website for the resort that shows the golf course

And the illegal golf course? It’s been built along with a resort of luxury RVs, personal saunas and a Disney-like castle to serve as the golf club. For this playground of the wealthy, Liu Yao got 20 years, pretty much a life sentence for this 56-year-old.

Since taking over the leadership in 2012, Xi Jinping has attempted to reassure foreign powers that China’s rise is peaceful. But all evidence points otherwise. In the summer, it was the unnecessary death of Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo while he was serving an 11 year prison sentence; last week it was the mysterious death of human rights lawyer Li Baiguang after being admitted to a state-run hospital for stomach pains; a few days ago it was Xi’s moves to eliminate term limits; and then there is Liu Yao’s 20 year sentence for exposing the corruption and injustice that Xi’s government has publicly stated it wants to eradicate. Increasingly, China’s rise – or more apt, Xi’s consolidation of power – has not been peaceful. It is time foreign government recognize that what is happening to China’s human rights defenders is not an outlier but is instead a reflection of the governing philosophy of Xi’s regime, both domestically and internationally. And it’s time they start to care and raise these issues publicly.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

While alarming, on some level Shi Fulong is lucky that the op-ed does not cite more although he is certainly bordering on the danger zone. Likely in an attempt to contain China’s civil rights lawyers, in the past couple of years, the Chinese’s government has sought to penalize and contain the zealous advocacy that is required of lawyers, especially civil rights lawyers. In the Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) recent

While alarming, on some level Shi Fulong is lucky that the op-ed does not cite more although he is certainly bordering on the danger zone. Likely in an attempt to contain China’s civil rights lawyers, in the past couple of years, the Chinese’s government has sought to penalize and contain the zealous advocacy that is required of lawyers, especially civil rights lawyers. In the Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) recent