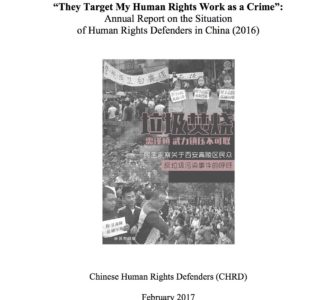

China Attempts Economic Globalization Without Human Rights

In July 2015, the Chinese government detained close to 250 lawyers, paralegals and activist in a nationwide crackdown on China’s nascent civil rights movement. The crackdown was unprecedented in its scope, with lawyers and activists simultaneously abducted from their homes and often in the dead of night. It seemed to signal the nadir for China’s rights activists but, as China Human Rights Defenders‘ (“CHRD”) Annual Report reflects, it was far from rock bottom. In 2016, the world witnessed the fallout from these arrests and a regime even more intent than ever on stamping out China’s civil rights movement. But while that fallout continues domestically, internationally, China is seeking to play a more important role and reshape the current global order. But the United States and western Europe – intent on pursuing more isolationist policies – ignores China’s domestic turmoil at its peril.

In July 2015, the Chinese government detained close to 250 lawyers, paralegals and activist in a nationwide crackdown on China’s nascent civil rights movement. The crackdown was unprecedented in its scope, with lawyers and activists simultaneously abducted from their homes and often in the dead of night. It seemed to signal the nadir for China’s rights activists but, as China Human Rights Defenders‘ (“CHRD”) Annual Report reflects, it was far from rock bottom. In 2016, the world witnessed the fallout from these arrests and a regime even more intent than ever on stamping out China’s civil rights movement. But while that fallout continues domestically, internationally, China is seeking to play a more important role and reshape the current global order. But the United States and western Europe – intent on pursuing more isolationist policies – ignores China’s domestic turmoil at its peril.

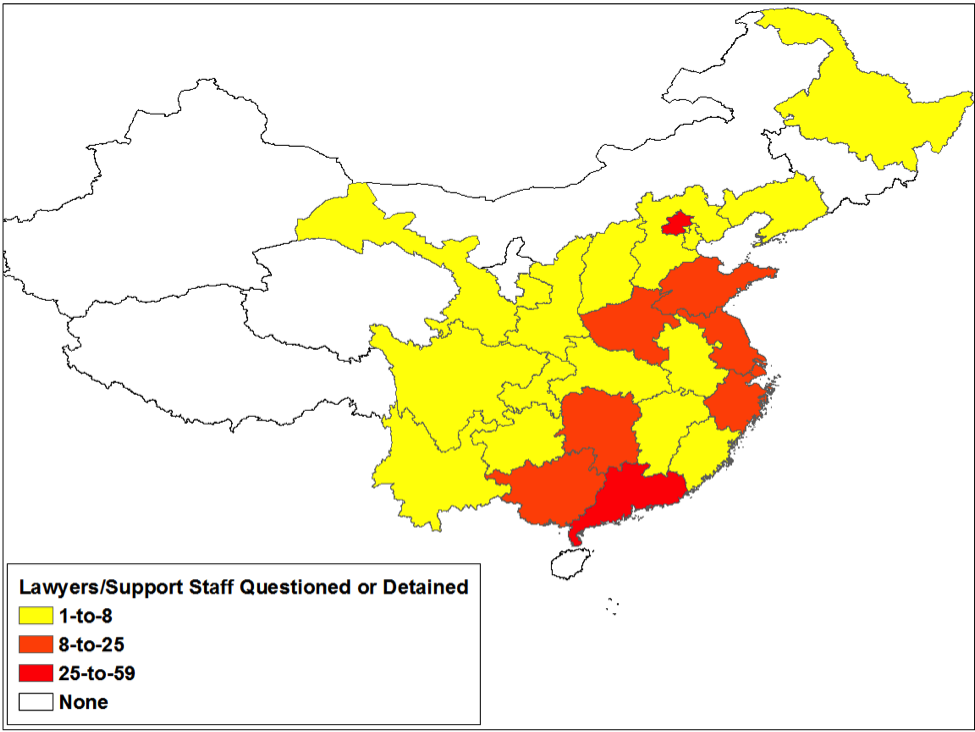

Map reflecting the national crackdown of Lawyers and support staff, July 2015 – October 2015 (courtesy of China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group)

2016: Things Just Got More Serious – Rights Lawyers & Activists Charged with National Security Crimes

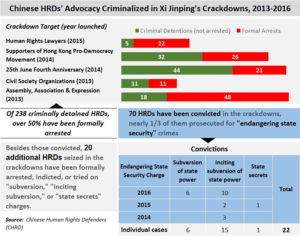

As CHRD’s 2016 Annual Report demonstrates, the Chinese government views these civil rights activists’ work – even activities as seemingly innocuous as bringing a lawsuit to test China’s commitment to its own laws – as a threat to its power. In 2016, these activists were not detained nor charged with the relatively minor crimes such as disturbing public order or unlawfully organizing a protest; instead, these arrested activist were charged with the more serious crimes that implicate national security issues and carry much heavier sentences. Look at what happened two years prior. In January 2014, Xu Zhiyong, an influential civil rights lawyer and activist, was convicted of “gathering crowds to disturb public order” (Criminal Law (“CL”), Art. 296)and sentenced to a prison term that was considered extreme at the time: four years. Fast forward to 2016 and Zhou Shifeng, one of the alleged “ringleaders” of the lawyers detained in July 2015, was convicted of subversion of state power (CL, Art. 105) and sentenced to seven years in prison.

And Zhou is not the only one. As CHRD portrays in a powerful chart in its Annual Report, in 2016, 16 rights activist were convicted of crimes relating to national security. Compare this to only three in 2015.

These more drastic charges of national security means that the police and prosecutors can all but abandon most due process rights enshrined in the amended Chinese Criminal Procedure Law. As the CHRD Annual Report notes, a national security investigation allows the police to unilaterally hold a suspect under “residential surveillance in a designated location.” With residential surveillance in a designated location, a location that is often unknown to the person’s family and lawyers, the police can legally hold a suspect for six months and, because the person is being investigated for a national security crime, the police can also lawfully deny access to an attorney. (For a case analysis of the laws surrounding residential surveillance in a designated location, see Codifying Illegality? The Case of Jiang Tianyong). Without access to a lawyer, contact with the outside world and likely subject to torture, CHRD’s 2016 Annual Report notes an uptick in a disturbing trend: televised forced “confessions” of rights activists before any trial.

2016: The Passage of Laws that Specifically Target Civil Society

China’s Foreign NGO Law is no lighthearted 1940s Hollywood movie.

But if these long prison sentences are not enough to squelch future rights activists, the Chinese government has adopted a series of laws to further restrict civil society. China’s Foreign NGO Law, passed in 2016 and went into effect on January 1, 2017, is an attempt to cut civil rights activists from contact with international civil rights organizations, especially those that provide financial support. In fact, as CHRD notes, in many of the recent prosecutions of rights activists, accepting foreign funding has been used as evidence of the activists’ subversion of state power. Foreign NGOs that the police believe engage in behavior that “endangers national security” are blacklisted. Presumably any Chinese person who interacts with these blacklisted foreign NGOs will likely be suspected of national security violations.

Similarly, the Charity Law makes it near impossible for many Chinese civil rights organizations to raise money domestically if they are not officially registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. Most likely those organic civil society groups that have been most effective but also have been viewed by the Chinese government – or more aptly the Chinese Communist Party – as a threat to its rule, will not receive permission to register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. As the stakes get higher, these organizations will likely cease to exist, eliminating an important channel that exposes societal discontent in an authoritarian regime.

(image courtesy of WCCF Tech)

But if those laws prove insufficient to completely eradicate any form of civil society not controlled by the government, in November 2016, the Chinese government passed its National Cyber Security Law which will provide for unprecedented surveillance of its citizens. Under the Cyber Security Law, the government has the right to restrict the internet to protect national security and social public order (Art. 58). Although implementation of the law has yet to be seen, presumably it can be used to shut down any online communication the Chinese government deems a security or public order threat. And as its recent prosecution on national security charges show, the Chinese government will likely view any efforts for civil rights activists to organize over social media to be a national security threat.

China’s Domestic Human Rights Conflicts With its Idea of “Economic Globalization”

President Xi at the 2017 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland (photo courtesy of Forbes)

While CHRD’s Annual Report reflects a deteriorating human rights situation, China’s star on the global stage has only risen, especially as the United States has elected an isolationist president. China’s most recent zenith came on January 17, 2017, when President Xi Jinping was granted the honor of delivering opening remarks at the Davos World Economic Forum, the world’s orgy to capitalism and globalization. In his speech, Xi called on the world to maintain its longstanding policies of “economic globalization,” implicitly distinguishing this concept from the liberal world order that created it.

For sure, Xi’s speech, calling on continued free trade, a policy that allowed China to quickly develop as an economic power, was a success at Davos. Especially as the United States and some parts of Europe retreat in their commitment to the world order they helped to put in place after World War II. But what Xi misses in his exclusive focus on “economic globalization” is that it does not exist in a vacuum. Economic globalization is only one aspect of the current liberal world order. Liberal political systems, liberal economics, more inter-connectedness among people of different countries cannot be eliminated from the post-World War II world order that brought the free trade Xi celebrates. All of these elements together is what has brought peace to much of the Western World and East Asia for close to 65 years, a peace that has been essential to China’s economic rise.

Setting up the post World War II order at Yalta in 1945

But Xi’s assault on Chinese civil society undermines these other essential elements of the world order. With the Chinese government’s constant attack on civil rights activists, this aspect of Chinese society lose the ability to impact China’s policy. Some of the issue Xi raised in his Davos speech – environmental protection and income inequality – are issues that the Chinese government was forced to confront because of pressure from its domestic civil society. But the Chinese government now seeks to cut off that important channel of protest.

But perhaps most dangerous is the Chinese government’s current vilification of anything foreign and its intent to keep its people separate from the rest of the world. The peace that much of the West and East Asia has experienced can be traced to the interconnectedness among people. But the Foreign NGO Law and the Chinese government’s persecution of activist who are connected to foreign organizations destroys that vital connection. The National Cyber Security Law only further exacerbates the internationally-isolated internet that already exists in China, keeping Chinese netizens separate from their compatriots in other countries.

Captain America, time to go back in your box! (image courtesy of Marvel Comics)

As the United States and some of Western Europe recede from the liberal world order to deal with their own domestic political turmoil, there will be space for other countries to step into positions of greater leadership on the global stage. China has demonstrated that it wants to. But with its continued assault on civil society and its increased xenophobia, are we sure this is what we really want?

************************************************************************************

China Human Rights Defenders’ 2016 Annual Report, entitled “They Target My Human Rights Work as a Crime,” can be found on their website here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email