The Human Cost of China’s One Child Policy – A Must See Documentary

To say that co-directors Wang Nanfu and Zhang Jialing’s One Child Nation is a tour de force is a ridiculous understatement; it is a scathing critique of the Chinese government’s continued willingness to sacrifice the souls of its people for its unilateral desire for economic development. Last week, the world remembered that trade-off when it commemorated the 30th anniversary of the Chinese government’s killing of peaceful protesters around Tiananmen Square, all in the name of stability and economic success. In One Child Nation, Wang and Zhang expose yet another of the Chinese government’s one-sided bargains: its violent enforcement of the one child policy.

In an effort to curb its rapidly growing population, between 1979 and 2015, the Chinese government instituted a one child policy. In a society that prizes children, and male children especially, restricting married couples to one child was never going to be a hit. And that’s how Wang and Zhang begin their film, showing the intense propaganda that was necessary to get the people’s buy-in. Reaching every city, town and village, the government indoctrinated the people into believing that having one child was their patriotic duty; those who had more than one were to be socially shunned. Even that propaganda took its toll. Wang, who was the first of two children during that era, admitted that growing up, she was embarrassed that she had a sibling, internalizing the propaganda that her family was using up the state’s resources and hindering China’s progress, all for their selfish interest of having a second child.

But as One Child Nation shows, propaganda was only the start. Quickly, the movie descends into the more horrific aspects of the Chinese government’s one child policy: the forced sterilizations, abortions and killing of babies.

By merely reading about these acts in the pages of the New York Times and other western newspapers over the years, it has been easy to shrug them off as isolated incidents. But One Child Nation makes clear that these were not one-off acts. And in showing the pictures of women being dragged, kicking and screaming, to be sterilized, or the almost full born fetuses that an artist collected after finding them in the trash, wrapped in a yellow plastic bag labeled “medical waste,” or the almost catatonic expressions on the everyday people who experienced the policy firsthand, either because they had to implement it or because it was their baby that had to be killed, One Child Nation ensures that you never forget.

And this is what makes One Child Nation so powerful and so successful in its condemnation of the one child policy and the Chinese government’s insistence on economic development no matter the human cost. Like nothing before it, One Child Nation visualizes the pain and suffering of the Chinese people, both the perpetrators of the policy and its victims. And the prevalence of these forced abortions and sterilizations become readily apparent when Wang interviews the village midwife. In the 20 years that she practiced, she preformed between 10,000 to 20,000 abortions and sterilizations. Quickly your mind does the math – if this is just one midwife in one rural village, the number of force abortions and sterilizations country-wide must be staggering.

But to truly understand the human and societal toll of China’s one child policy, Wang centers the film on her family in rural Jiangxi province, a brave choice that is a testament to Wang’s commitment to letting the world know what happened as opposed to protecting the privacy of her family. While Wang is very much aware of the cruelty of the one child policy, her family do not appear to be. There are moments in some of Wang’s interviews with her relatives – where they can speak so nonchalantly about the abandonment of a baby – that makes one cringe. But then it is easy for us in the Western world to cringe; we never had to experience a policy that required such a choice.

Propaganda poster from the time period

One example is Wang’s interview with her mother, when she admits that she helped her uncle abandon the uncle’s newborn daughter, in a market, hoping someone would pick her up. For Wang’s relatives, the logic was clear: abandon the girl and try for a son. But no one else wanted a baby girl, and by the second day, with a body covered in mosquito bites, Wang’s cousin died.

Another of Wang’s female cousins was sold to a trafficker. Luckily, this cousin was born later than the first one, when the market for international adoptions began to flourish with the Chinese government lifting of its ban on foreign adoptions in 1992. Instead of leaving girls to die, mothers could sell them to traffickers for placement in an orphanage. Unfortunately, as One Child Nation demonstrates, the market for these adoptions became so profitable that traffickers and government officials began stealing girls from rural families that had more than one child, even if these families had paid the fine.

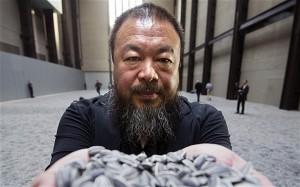

For almost 40 years, the Chinese people – especially women in the rural areas – have had to undergo tremendous suffering under China’s one child policy. In a particularly moving montage, Wang and Zhang splice together each of their interviewees’ response to one question: why. And each says the same thing: there was nothing they could do. Only one person was able to express the pain of the one child policy – the 16 year-old whose identical twin sister was stolen from her family, sold to traffickers and now lives in the United States.

As One Child Nation makes clear, the question “why” needs to be asked of the Chinese government: why must the Chinese people continue to suffer because of its unilateral decision to seek economic gain at all costs, including trampling on people’s basic human rights. After the government-made famine of the Great Leap Forward, the shattering of traditional bonds in the Cultural Revolution, the murder of unarmed civilians near Tiananmen Square, and now the societal toll of the one child policy, when will the Chinese people be able to have a say as to whether their sacrifice is worth it?

The human toll of China’s one child policy; this girl’s identical twin sister is in America

Masterfully directed and powerfully curated, One Child Nation finally gives the Chinese people their voice. And what they are saying – that denying them their dignity could never be worth it – is not something the Chinese government wants to hear, especially as it peddles abroad its model of economic development above all other human rights. Unfortunately, the United Nations has become a receptive audience. In an April speech in Beijing, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres’ sole focus was on economic development and how Beijing’s current international economic platform of the Belt and Road Initiative was perfectly aligned with the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. There was no mention of the danger to other human rights that could arise if the singular focus is economic development or the need to ensure that those human rights are also allowed to flourish on an equal footing with economic development. But One Child Nation makes clear that those other rights desperately need to be protected; if they are not, then governments will be able to inflict any human rights violations they want all in the name of economic development. While this is a movie everyone must see, Antonio Guterres in particular would be well-advised to see this movie before he once again applauds the Chinese government for its economic development. It’s time he – and the world asks – at what cost?

Rating:

Next Showings: Nantucket, MA – June 19 – 24, 2019 at the Nantucket Film Festival; and Washington, D.C. – June 19 – 23, 2019 at the AFI Docs Film Festival. One Child Nation is supposed to have a nation-wide release on August 9, 2019. To stay up to date on One Child Nation, check out the film’s website here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email