U.S. President-elect Donald Trump (left) and Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen

Every four years, leaders from around the world call the newly-elected president of the United States, congratulating him on winning his country’s election. Although a quaint custom, there is a lot of backroom dealing that goes on before the two leaders talk: staff has to ensure that it isn’t a prank, that translators are on hand if necessary, and that an agenda and time is appropriately set.

But one thing that never happens is a congratulatory phone call between a U.S. president-elect and the President of Taiwan. That is because for the past 40 years, the U.S. has not recognized Taiwan as a separate country; to take an official phone call from the President of Taiwan signals a possible change in the United States’ “one-China policy,” potentially inciting the anger of the People’s Republic of China (“Mainland China,” “China” or “PRC”), and potentially undermining the tense status quo between Mainland China and Taiwan.

Hotline Bling! President-elect Trump on the phone (photo courtesy of CNN.com)

And that is why President-elect Donald Trump’s decision, on December 2, to accept a phone call from Tsai Ing-wen, the current president of Taiwan, was such a shock and front page news across the globe. Although originally downplayed by his transition team, Trump doubled-down only a few days later where, in an interview with Fox News, he stated that he doesn’t “know why we have to be bound by a One-China policy unless we make a deal with China having to do with other things. . . .”

But if Trump is sincerely thinking that such a policy shift would benefit Taiwan or thinking that this is a good way to strong arm Mainland China on other issues, he will likely be proven dead wrong. Toying with China about Taiwan is not going to give the U.S. the upper hand in its relations with China. For almost 70 years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has tied its legitimacy to the eventual reunification of Taiwan with the Mainland. For the U.S. to make overtures that it might abandon the one-China policy goes to the heart of the CCP’s rule. Because of this, the CCP will not respond lightly – nor necessarily in accordance with what we think might be rational – to President-elect Trump’s public insinuations of a shift in the one-China policy.

The Creation and Evolution of the One-China Policy

1971 PRC Propaganda Poster: “We will definitely liberate Taiwan!”

The one-China policy is not the brain child of the United States. Rather, it is a concept created in 1949, after the Chinese Civil War, by the leaderships of both Mainland China and Taiwan. Up until 1949, Mainland China, of which Taiwan was a part, was called the Republic of China (“ROC”) and was ruled by the Kuo Mintang party (“KMT”), under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek. But on October 1, 1949, the CCP gained control of Mainland China, establishing the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”) and the KMT and its supporters fled to the island of Taiwan.

On Taiwan, Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT re-established the Republic of China. Both the CCP and the KMT agreed there was only one China, a China that includes the Mainland and Taiwan; both agreed that eventually the Mainland and Taiwan would be re-united. Where the two states differed was to which was the legitimate leader of this phantom one-China. For the KMT, the ROC in Taiwan was the legitimate China with the mainland consisting of renegade provinces that would eventually be re-united under KMT rule. For the CCP, the opposite held true: it was the PRC that was the legitimate government, Taiwan was a wayward province that would eventually be re-united with the mainland under CCP rule.

U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Chinese President Deng Xiaoping sign the accords where the US switches recognition to the PRC

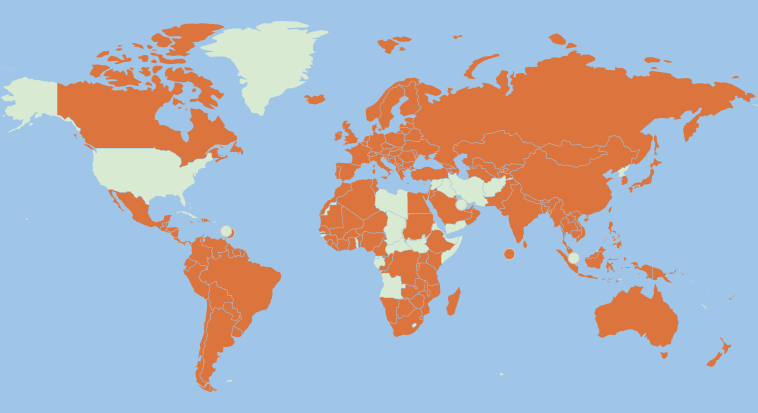

Because of the CCP and KMT’s one-China concept, the rest of the world had to choose “one China” to recognize and establish diplomatic ties. Neither Taiwan nor the Mainland would allow a country to recognize both Chinas. Like most things during the Cold War, the choice was political. Between 1949 and the early 1970s, almost all western, democratic countries recognized the ROC on Taiwan as China and most communist countries recognized the PRC on the mainland as legitimate China.

By the early 1970s, things began to change and in 1979, the United States switched its formal diplomatic recognition to the PRC. As a result, the United States cut off all official diplomatic relations with Taiwan, closing its embassy in Taipei.

But only official diplomatic ties were severed. The United States continued to maintain strong economic and military ties with Taiwan. In fact, to show that the United States was not completely abandoning Taiwan, in 1979, Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act. The Act didn’t just create the American Institute in Taiwan (“AIT”), a non-profit organization, funded by the U.S. government and serving as a de facto embassy in Taipei, it also, by committing the U.S. to make available “defense articles and defense services,” tied U.S. military support to the island. Since the passage of the Act, the United States has sold over $30 billion in defensive military arms to Taiwan; $14 billion of that has been under the Obama Administration.

For Mainland China, the One-China Policy Is Not A Joke

For Mainland China, the belief that Taiwan is an indispensable part of China and will eventually be re-united is sacrosanct. It is the line the CCP has been propagating to its people since 1949 and which the majority of the Chinese people believe. Enshrined in preamble to the PRC Constitution is the notion that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the PRC and will be re-united with the Mainland. Every time relations between Taiwan and another country gets too cozy, the CCP, through the state-run media, vehemently criticizes the offending nation for interfering in their internal affairs.

For Mainland China, the belief that Taiwan is an indispensable part of China and will eventually be re-united is sacrosanct. It is the line the CCP has been propagating to its people since 1949 and which the majority of the Chinese people believe. Enshrined in preamble to the PRC Constitution is the notion that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the PRC and will be re-united with the Mainland. Every time relations between Taiwan and another country gets too cozy, the CCP, through the state-run media, vehemently criticizes the offending nation for interfering in their internal affairs.

As China’s economy continues to lag, the CCP’s promise of constant economic property for its people is undermined, making its nationalist promises of a one-China even more necessary to fulfill. For the CCP, failure to fulfill that promise threatens its rule. And the CCP has no interest in relinquishing its rule.

But for the Taiwanese people, the concept of one China has evolved especially as the KMT has lost its complete control of the island’s political system. From 1949 to the early 1990s, Taiwan was a one-party country, with the KMT and its allegiance to the one-China policy, in control. However, starting in the mid 1990s, a new political party emerged on Taiwan, the Democratic Progressive Party (“DPP”). The DPP rejects the idea of a one-China. It even rejects the idea of a two-China. Instead, it maintains that Taiwan has become a separate country and culture, distinct from Mainland China. For the DPP, there is only one China, the Mainland, and then there is Taiwan.

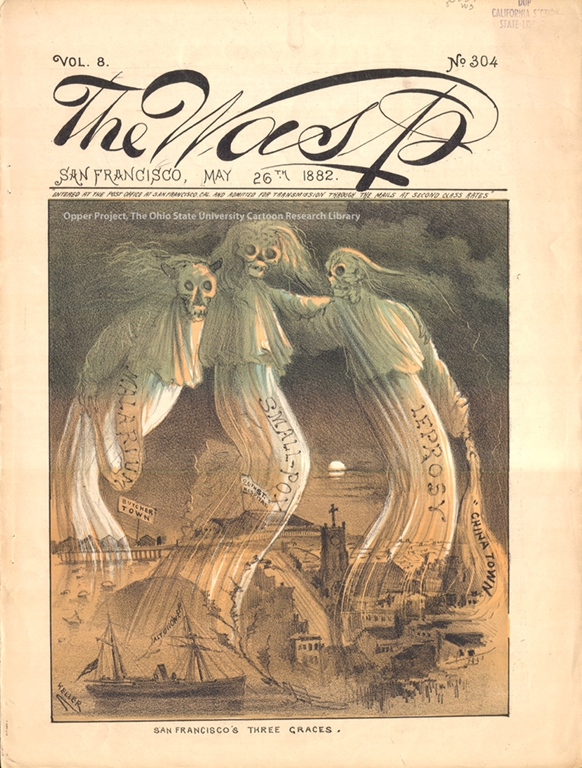

Taiwanese protesters who oppose the One China Policy

In 2000, when DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian won the presidency, the CCP grew fearful. With the increased stature of the DPP in Taiwan and the fact that it can win national elections, China has built up its military to be capable of dealing with Taiwan if the country should ever publicly repudiate the one-China policy and change its laws to establish the independent country of Taiwan. After Chen won a second term in 2004, the CCP decided to make its intentions more clear. In 2005, the CCP passed a new law – the Anti-Secession Law – exclusively about the Taiwan situation. While it continues to call for the peaceful reunification of the Mainland with Taiwan, Article 8 of the Anti-Secession Law makes it clear that China will use force if Taiwan declares its independence. In 2015, the CCP passed the National Security Law, a sweeping law that seeks to expand and reinforce China’s international reach. Article 11 mentions sovereignty over Taiwan.

While the Taiwanese people have elected a DPP president in 2000, 2004 and then again with current President Tsai in 2015, the Taiwanese repeatedly prefer to maintain the status quo in their relationship to the Mainland.

The Trump Call Is More Than A Phone Call

Taiwanese protesters supporting the One China Policy

It is within this powder keg – two entities armed to the teeth, one voting in an “independence party” and the other feeling insecure with its economic slowdown – that President-elect Trump decided to accept Taiwan President Tsai’s call, feigning ignorance that the call was somehow not monumental. Not surprisingly, China’s reaction was quick and angry. But in ways, less so toward the U.S. than to Taiwan. In an op-ed in the state-run Global Times, the CCP reminded Taiwan that it would not hesitate to “punish” Taiwan and that Taiwan must pay the price if it breaks the status quo.

True the one-China policy is increasingly a rotten deal for Taiwan, especially as China seeks to use its might to squeeze Taiwan out of important international organizations and meetings, including meetings held recently by the U.N. and Interpol. And there might be reasons to re-calibrate some of the customs surrounding the one-China policy. Currently, the Taiwan Travel Act, which would permit officials from the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office (Taiwan’s de facto embassy in the U.S.) to conduct official business with the U.S. government, is pending before Congress. Additionally, last year Congress passed, and President Obama signed into law, a bill requiring the U.S. State Department to develop a strategy to obtain observer status for Taiwan at Interpol. When President Tsai travels to Latin America this month, the Obama Administration has agreed, regardless of China’s protests, to grant her a “transit visa”, allowing her to meet with people while on U.S. soil. The U.S.’ continued advocacy to ensure Taiwan’s inclusion as an important international entity is not only a benefit to Taiwan but also a benefit to the rest of world as it permits an East Asian state with an democratically-elect government and vibrant civil society to serve as a counter-example to China.

But President-elect Trump’s December 2 call with President Tsai does not come off as a well thought out and effective means to bolster Taiwan’s place in the world. Based on his follow-up interview with Fox News, the call appears to have been solely a strategy to anger Beijing in an attempt to work out a better trade deal for the U.S. But Taiwan – and the one-China policy – is too essential of an issue for the CCP to simply bargain for as if this is a mere business deal.

But President-elect Trump’s December 2 call with President Tsai does not come off as a well thought out and effective means to bolster Taiwan’s place in the world. Based on his follow-up interview with Fox News, the call appears to have been solely a strategy to anger Beijing in an attempt to work out a better trade deal for the U.S. But Taiwan – and the one-China policy – is too essential of an issue for the CCP to simply bargain for as if this is a mere business deal.

If Trump continues to carelessly trifle with the one-China policy, it will be Taiwan and its people that will bear China’s initial wrath. But with the U.S.’ ostensible obligation under the Taiwan Relations Act to support Taiwan defensively, it could very well be American lives that are also at stake.

For a thoughtful rebuke of President-elect’s phone call with President Tsai, please read former American Institute in Taiwan senior official and China expert Richard Bush’s “Open Letter to Donald Trump on the One-China Policy”: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2016/12/13/an-open-letter-to-donald-trump-on-the-one-china-policy/

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

For Mainland China, the belief that Taiwan is an indispensable part of China and will eventually be re-united is sacrosanct. It is the line the CCP has been propagating to its people since 1949 and which the majority of the Chinese people believe. Enshrined in preamble to the PRC Constitution is the notion that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the PRC and will be re-united with the Mainland. Every time relations between Taiwan and another country gets too cozy, the CCP, through the state-run media, vehemently criticizes the offending nation for interfering in their internal affairs.

For Mainland China, the belief that Taiwan is an indispensable part of China and will eventually be re-united is sacrosanct. It is the line the CCP has been propagating to its people since 1949 and which the majority of the Chinese people believe. Enshrined in preamble to the PRC Constitution is the notion that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the PRC and will be re-united with the Mainland. Every time relations between Taiwan and another country gets too cozy, the CCP, through the state-run media, vehemently criticizes the offending nation for interfering in their internal affairs.

But President-elect Trump’s December 2 call with President Tsai does not come off as a well thought out and effective means to bolster Taiwan’s place in the world. Based on his

But President-elect Trump’s December 2 call with President Tsai does not come off as a well thought out and effective means to bolster Taiwan’s place in the world. Based on his