French journalist Ursula Gauthier

In recent years, the Chinese government has taken a passive-aggressive approach with the foreign press, keeping many foreign journalists on pins and needles during the annual accreditation renewal process. But with the impending expulsion of French journalist Ursula Gauthier, the Chinese government has opted for a different approach: downright aggressive.

On December 26, 2015, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) confirmed that it denied Gauthier’s application to renew her press card (official English version here), effectively resulting in her expulsion from China since her journalist visa – set to expire on December 31 – cannot be renewed without a valid press card. MOFA found Gauthier “no longer suitable to continue working in China” because her November 18, 2015 article in the French newsmagazine, L’Obs, “championed acts of terrorism and the slaughter of innocent civilians . . .”

In response, Western social media is ablaze with criticism of the Chinese government, calling its accusations against Gauthier unfounded and an attempt to censor the foreign press. And while these critiques may be true, the question still remains: are MOFA’s acts legal under Chinese law. Unfortunately, with laws and regulations that are increasingly vague and broad, the answer is yes.

Gauthier’s Article: Why the Chinese Government’s Panties Are All in a Bunch

Shanghai’s skyline lit up in memory of the lives lost in Paris in the Nov. 13, 2015 attacks. (Photo courtesy of CNN)

As L’Obs‘ Beijing correspondent, Gauthier witnessed the Chinese government and people’s outpouring of sympathy for the French people as a result of the November 13, 2015 terror attacks in Paris. Chinese students left bouquets of flowers at the French Embassy; President Xi Jinping expressed his condemnation of such “barbarous actions;” and Shanghai lit up its Oriental Pearl TV Tower in the French tri-colors of blue, white and red.

But at the November 15, 2015 G20 Summit in Antalya, Turkey, the Chinese government sought to transform its feelings of sympathy into ones of action. Stating that there can be “no double standards,” MOFA spokesperson, Wang Yi, called on the global community to support China’s anti-terrorism efforts in its far-western province of Xinjiang (pronounced Sin Gee-ang).

In the past few years, hundreds of innocent Chinese citizens have been violently killed in Xinjiang in mass attacks, usually perpetrated by members of the Uighur minority, a Muslim, Turkic-speaking population that dominates the province. Some of that violence has spilled to other parts of China most notably the 2013 suicide attack at Tiananmen Square and a 2014 rampage in a Yunnan bus station.

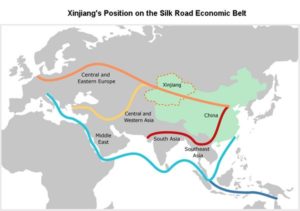

While this violence cannot be denied, there is significant doubt as to how many of these attacks are attributable to international terrorist organizations – as the Chinese government claims – or are merely the natural result of a Muslim population increasingly frustrated at the Chinese government’s restrictive policies concerning the practice of their religion.[1] The Chinese government references the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, an international separatist movement, as the perpetrators of these domestic attacks. But some Western scholars debate the group’s existence. Although the Islamic State (ISIS) has issued a call for recruits in Mandarin, it is unclear the extent of ISIS’s impact in Xinjiang. And by essentially sealing off independent foreign reporting from Xinjiang, the Chinese government does nothing to ensure that there is greater understanding as to what is really happening in the region.

2013 car bomb at Tiananmen Square (courtesy of the Daily Mail)

With this backdrop, on November 18, Gauthier published an essay in L’Obs highlighting that the Chinese government’s call for the international community to join its fight against terrorism was misplaced (rough English translation here). In “After the Paris Attacks, China’s Solidarity is Not Without Ulterior Motives,” Gauthier rejects the Chinese government’s claim that the current wave of violence in Xinjiang is the result of global terrorism. Instead, Gauthier maintains that much of the violence is likely the result of the Chinese government’s repressive policies toward Uighurs.

For Western readers, Gauthier’s sentiment is neither shocking nor new. Arguably, it has become par for the course. After almost every terrorist attack in the West, articles appear questioning the impact of the government’s policy toward the ethnic minority. After the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks, plenty of articles questioned whether the attacks were also the result of France’s harsh policies toward its Muslim population and difficulty integrating into French society (see here, here and here). After the 2004 murder of Dutch film director Theo Van Gogh, Ian Buruma wrote an entire book analyzing the impact of Dutch immigration and assimilation policies on the murderer’s mindset. Gauthier’s article, while a bit more stinging, was in a similar vein.

But in series of op-eds in the Global Times and the English language version of the China Daily, the state-controlled press criticized Gauthier for having a “double standard” and, by not focusing on the death of innocent Chinese victims in the Xinjiang attacks, devaluing the lives of Chinese people vis-a-vis the French. If the Chinese government left its criticism of Gauthier’s piece at this, it would not necessarily be out of the ordinary or irrational. It wasn’t until after the non-stop press coverage of the Paris attacks and the outpouring of sympathy on social media did it come out that a mere day earlier dozens had been killed by an ISIS-inspired attack in Lebanon. In the U.S., part of the Black Lives Matters movement is to highlight the double standard by the U.S media in covering stories that impact the white population over the black population.

But the state-run media did not leave it at that. Instead, it ratcheted up its rhetoric. On December 2, 2015, at a MOFA press conference, spokesperson, Hua Chunying, publicly criticized Gauthier. Over the next few weeks, MOFA met with Gauthier at least three times, demanding that she apologize for her essay. In addition, Gauthier’s address was leaked online even though in some of the responses to the Global Times op-ed, people were threatening her life. On December 26, MOFA denied her application to renew her press card, maintaining that she advocated terrorism and violence, an accusation no where evident in a reading of her November 18 piece.

China’s Recent Attempts to Use the Press Accreditation Process to Censor Foreign Journalists

Regardless of the validity of the Chinese government’s accusations against Gauthier, by denying her press card and thus her ability to report from China, the Chinese government has effectively silenced her. This is not the first time the Chinese government has used the press accreditation process as a form of retribution or an attempt to censor foreign journalists. But even in light of this fact, Gauthier’s case is shockingly different, with the Chinese government, after a ruthless campaign against her, publicly admitting that its decision to effectively expel Gauthier was a direct result of her reporting.

For resident journalists in China, the journalist visa (“J-1 visa”) and the press card are only good for a year, expiring every December. Beginning in November, every resident foreign journalist begins the renewal process, first re-applying with MOFA for a new press card and then, once obtaining the press card, renewing her J-1 visa with the Public Security Bureau’s (PSB) Exit/Entry Department. For those who change employers in the middle of the year, the process to renew the press card with the name of a new employer, begins earlier in the year when the employment change occurs.

For resident journalists in China, the journalist visa (“J-1 visa”) and the press card are only good for a year, expiring every December. Beginning in November, every resident foreign journalist begins the renewal process, first re-applying with MOFA for a new press card and then, once obtaining the press card, renewing her J-1 visa with the Public Security Bureau’s (PSB) Exit/Entry Department. For those who change employers in the middle of the year, the process to renew the press card with the name of a new employer, begins earlier in the year when the employment change occurs.

Aside from the 2012 expulsion of Al Jazeera English’s Melissa Chan, who, unlike Gauthier, did not receive any public condemnation, all of the foreign reporters forced to leave China in the past three years have departed due to an alleged paperwork snafu.[2] These reporters were not denied their press credentials. Instead, MOFA ignored their applications due to irregular or improper paperwork. Conveniently, MOFA did not discover these paperwork issues until the eve of – or in some cases, after the expiration of the reporter’s visa.

Philip Pan, New York Times Asia Editor now based out of Hong Kong

All three of these reporters, Philip Pan, Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, were with the New York Times causing most in the West to speculate that these departures were not a simple paperwork issue.[3] Instead, the commonly held belief is that each departure was the Chinese government’s retaliation against the New York Times for its Pulitzer Prize-winning series that exposed the depth of former Premier Wen Jiabao’s finances and the profits his family has acquired over the years.

But it appeared that the Chinese government’s abuse of the foreign journalist accreditation process reached its peak in January 2014, with New York Times reporter Ramzy’s departure. In fact, in its 2015 survey, the Foreign Correspondents Club of China (FCCC) noted that there was a decrease in complaints from its membership regarding the visa and press card renewal process, with 93% of respondents stating that they were issued their J-1 visa within the stipulated time period.[4]

By the middle of 2015, it appeared that the Chinese government was mellowing in its attempt to censor the foreign press through the accreditation process. After Xi’s visit to the United States in September 2015, Chris Buckley, after a three year wait, was finally able to obtain a J-1 visa and return to China. Similarly, also after Xi’s visit, new New York Times China correspondent, Javier Hernandez was able to obtain his J-1 visa after waiting since at least early 2015.

Chris Buckley, New York Times reporter now based in Beijing after a three year wait in Hong Kong.

But the situation with Gauthier isn’t just a step back – it’s a whole new approach. In the past, the Chinese government was coy with its reasons to deny a press card or a J-1 visa. With Chan in 2012, it merely stated that its decision was in accordance with law. With Pan, Buckley and Ramzy, MOFA used the excuse of a paperwork error that it was unaware of for months even though it’s in the business of processing such applications. But with Gauthier, the Chinese government is not attempting to hide its reasons for denying her a press card. It has explicitly tied its decision to her November 18 essay.

Can MOFA Deny a Press Card for Reporting it Does Not Like?

While MOFA itself has not explained the basis in the law for tying press accreditation to a specific article, an interesting piece published by Beijing Youth Daily heavily hints at the source. The Beijing Youth Daily piece notes that Gauthier, like all foreign journalists, is subject to MOFA’s “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on News Coverage by Permanent Offices of Foreign Media Organizations and Foreign Journalists” (Foreign Media Regs) (official English translation here). Article 21 of the Foreign Media Regs gives MOFA the power, in serious circumstances, to revoke a foreign journalist’s press card when the journalist violates the Foreign Media Regs.

The Foreign Media Regs, which is more about the process of setting up a foreign media office and obtaining a press card, do not delineate which topics are off limits for foreign journalists. There is no mention about reporting on Xinjiang, Uighurs or even terrorism. But, as the Beijing Youth Daily post notes, Article 4 requires foreign journalists to “abide by the laws, regulations and rules of China, observe the professional ethics of journalism, conduct news coverage and reporting activities on an objective and impartial basis,” and “not engage in activities which are incompatible with the nature of the organizations or the capacity as journalists.”

It is this provision, which if necessary, MOFA will likely cite to for its authority to deny Gauthier her press card as a result of her November 18 article. By “championing terrorism,” MOFA has essentially stated that Gauthier has not reported “on an objective and impartial basis,” thus violating Article 4 of the Foreign Media Regs and granting MOFA the authority – through Article 21 – to deny her press card application.

Under Article 4 of the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA does not have to criminally prosecute Gauthier for a crime or even give her any form of due process (such as appealing the decision). Under the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA is the judge and jury of violations of the Regulations and with Article 4’s broad strokes, it is easy to find a foreign journalist in contempt of the Regulations. So for those foreign journalists who thought the worst was over in terms of the annual visa renewal process, think again. While Article 4 has been on the books for a while, China is now not afraid to use it. Welcome to Foreign Press Accreditation Process Version 2.0.

Under Article 4 of the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA does not have to criminally prosecute Gauthier for a crime or even give her any form of due process (such as appealing the decision). Under the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA is the judge and jury of violations of the Regulations and with Article 4’s broad strokes, it is easy to find a foreign journalist in contempt of the Regulations. So for those foreign journalists who thought the worst was over in terms of the annual visa renewal process, think again. While Article 4 has been on the books for a while, China is now not afraid to use it. Welcome to Foreign Press Accreditation Process Version 2.0.

********************************************************************************************************************

[1] For example, in 2015, certain cities in Xinjiang forbade fasting during Ramadan for civil servants, teachers and students. In 2014, Shaya County in Xinjiang forbade men from wearing beards in public and called on the public to report them. In 2015, taking a cue from the French laws, the capital of Xinjiang forbade women from wearing burqas in public.

[2] While not expelled from China, in November 2013, after waiting over eight months for his journalist visa, former South China Morning Post reporter Paul Mooney was denied accreditation. MOFA merely stated that its decision was in accordance with the law. Because Mooney was applying for accreditation from the United States for his new employer Reuters, this is not an expulsion from China. However, it was a denial and thus, does not fit into the category of “paperwork snafu.” Many in the Western press speculate that Mooney’s press card denial was the result of his hard-hitting reporting on China’s human rights violations.

[3] Pan’s departure from China is the least reported on and thus the least understood. However, if Pan had been denied a press card or J-1 visa, this fact would have been reported in the press. As a result, it is highly likely that Pan’s application was simply not processed due to some other reason such as a paperwork issue.

[4] The FCCC’s “2015 Annual Working Conditions Report” is on file with China Law & Policy. To obtain a copy, please email fcccadmin@gmail.com.

When I started seeing the Grayzone, a website that describes itself as “dedicated to original investigative journalism,” touted in various Chinese media reports (see here and here) for a study that allegedly debunked the estimate of one million Uighurs detained in internment camps in Xinjiang, I felt like I had to read it. But to call the Grayzone piece an analysis – or even objective journalism – would be a serious overstatement. Instead, Ajit Singh and Max Blumenthal, the authors of “China detaining millions of Uyghurs? Serious problems with claims by US-backed NGO and far-right researcher ‘led by God’ against Beijing,” largely dedicate their piece to the character assassination of the two organizations/people who first estimated the one million figure: the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) and Adrian Zenz, a social scientist at the European School of Culture & Theology and now a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

When I started seeing the Grayzone, a website that describes itself as “dedicated to original investigative journalism,” touted in various Chinese media reports (see here and here) for a study that allegedly debunked the estimate of one million Uighurs detained in internment camps in Xinjiang, I felt like I had to read it. But to call the Grayzone piece an analysis – or even objective journalism – would be a serious overstatement. Instead, Ajit Singh and Max Blumenthal, the authors of “China detaining millions of Uyghurs? Serious problems with claims by US-backed NGO and far-right researcher ‘led by God’ against Beijing,” largely dedicate their piece to the character assassination of the two organizations/people who first estimated the one million figure: the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) and Adrian Zenz, a social scientist at the European School of Culture & Theology and now a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

Rajagopalan’s Reporting on Xinjiang – Why Is the Chinese Government So Sensitive About This?

Rajagopalan’s Reporting on Xinjiang – Why Is the Chinese Government So Sensitive About This?

Unlike the United States, where there is only one type of journalist visa, Chinese law distinguishes between two types of journalist visas, the J-1 and the J-2. The J-1 visa can only be issued to journalists whose news agency has a permanent office in China (See

Unlike the United States, where there is only one type of journalist visa, Chinese law distinguishes between two types of journalist visas, the J-1 and the J-2. The J-1 visa can only be issued to journalists whose news agency has a permanent office in China (See

Under Article 4 of the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA does not have to criminally prosecute Gauthier for a crime or even give her any form of due process (such as appealing the decision). Under the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA is the judge and jury of violations of the Regulations and with Article 4’s broad strokes, it is easy to find a foreign journalist in contempt of the Regulations. So for those foreign journalists who thought the worst was over in terms of the annual visa renewal process, think again. While

Under Article 4 of the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA does not have to criminally prosecute Gauthier for a crime or even give her any form of due process (such as appealing the decision). Under the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA is the judge and jury of violations of the Regulations and with Article 4’s broad strokes, it is easy to find a foreign journalist in contempt of the Regulations. So for those foreign journalists who thought the worst was over in terms of the annual visa renewal process, think again. While