A Thorn in the Government’s Side – China’s Human Rights Advocates

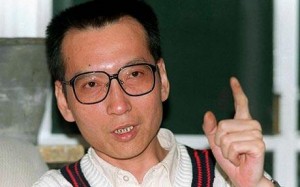

Since the fall, not a month has gone by where there isn’t some Chinese human rights advocate being prosecuted. The charge is usually the vague and broad claim of “disturbing public order.” Activist Xu Zhiyong (pronounced Sue Zhi young) was given four years in January under that charge, one year shy of the maximum. Cao Shunli (pronounced Ts-ow Shun lee), another human rights, died in police custody while being investigated for the same charge.

Who are these human rights advocates and lawyers? And why has the Chinese government become increasingly harsh? To put this all in is Prof. Eva Pils, an associate professor of law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and research fellow at NYU’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute. In 2006, Prof. Pils wrote the seminal article on human rights lawyers in China, Asking the Tiger for His Skin: Rights Activism in China. This summer, Prof. Pils will continue her work with a book on rights activism entitled China’s Human Rights Lawyers: Advocacy and Resistance. Last month, as more human rights advocates and lawyers were being detained, Prof. Pils sat down with China Law & Policy.

Read the transcript below of Part 1 of this three-part interview or click on the media player below to listen:

Length: 14:49 minutes

***************************************************************************************************************

EL: Thank you for joining us today Prof. Pils. Let’s start with a little bit of background. These human rights lawyers, who are most frequently referred to as “rights defense” or “rights defending” lawyers, when did they first start to emerge and why?

EP: Thank you. I think that they used to call themselves ‘rights defense – weiquan [维权] lawyers’ – but I think that actually over

the past one or two years, they’ve started preferring the term renquan lushi [人权律师] which means ‘human rights lawyers.’ That’s in a way related to how they emerged. They emerged because in the post-Mao era, especially from the 1990s onward, it became possible to use the law to defend rights, for one thing of course because there [now] was law — it was only under the Deng Xiaoping reform and opening policies that law became an accepted tool of government of the Party-State, after it had been completely denounced in essence as a counter-revolutionary idea in the last decade under Mao Zedong

Then the other thing is that there was a period, [from the beginning of the post-Mao era until] the 1990s when the Party-State authorities were essentially encouraging the use of law to address certain kinds of dispute, certain kinds of conflict in society. During that time, weiquan – rights defense – was actually an officially propagated term. As background, one would have to say that rule by law – yifa zhiguo [依法治国] – was an idea that the authorities were making use of in the Deng Xiaoping era in order to claim political legitimacy. That in a way replaced the political legitimacy coming from the idea of a communist revolution that was what political legitimacy was based on in the Mao Zedong era.

I think that this argument [about law as a tool of governance] is quite right, this is how Deng Xiaoping wanted to develop China in the post-Mao era, but also I think that the authorities, perhaps including Deng Xiaoping, didn’t fully realize what they were letting themselves in for when they promoted the idea of [rule by law and] weiquan. Perhaps this was because they were quite good Marxist-Leninists and believed sincerely that law was nothing other than a tool of governance to be used by the ruling power. Whereas of course, from the weiquan or rights defense perspective, [law] is connected to justice and it’s connected also, potentially at least, to political resistance, to the idea of rights, of human rights. I think that it’s a step toward a more explicitly political agenda that the lawyers who used to be referred to as weiquan lawyers have now chosen to call themselves human rights lawyers.

EL: In terms of the political agenda, the agenda of the human rights lawyers in China, in terms of their issues – is there something that unifies them as a single issue or are there different issues? In general, are they located in one area or do you find them throughout the country.

EP: I think in terms of area, definitely there is a huge concentration in Beijing and also in a couple of other cities, in particular Guangzhou and of course also Shanghai. But when you look at how they work and where they work, it is very important to see that they really work all across the country. In the Jiansanjiang case you mentioned just before [the interview] you have a couple of human rights lawyers going to this extremely remote location in Heilongjiang with the purpose of freeing, or in any case providing legal support to, a couple of people who are extra-legally detained there. That’s an example of what human rights lawyers do regardless of where they are based.

Is there something that unifies them? My impression in having done so many hundreds of interviews over the past couple of years with, I suppose, a few dozen human rights lawyers, [is that] they are very diverse, they are very different in terms of their personalities, their approach to their work, and in some of their convictions. But there are things that do unite them. I think that for one thing, they see themselves as adopting different methods from what many other lawyers are prepared to do. For instance, they reject the idea of wining and dining the officials concerned in their clients case to get results. In that, they’re not different from a group of lawyers called sikepai [死磕派] lawyers, lawyers who are very uncompromising. But what sets them apart from the sikepai lawyers is that they are willing to take on cases that nobody else will want to touch. I suppose one good example for that is the cases of people who practice Falun Gong. And thirdly, they [human rights lawyers] have recently started identifying more clearly around political ideas. They want democracy.

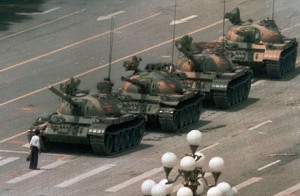

The more things change, the more they remain the same – 25 years after Tiananmen, still cracking down on dissent

EL: Just in terms of the crackdowns that we are seeing and I think you talk a little bit about this in your previous answer. There has always been a crackdown on dissent in the People’s Republic of China, even in the post-Mao era. You see the 1978 Democracy Wall movement, there is a crackdown. You see the Tiananmen protests of 1989, there is a crackdown. Should we be surprised that the same Chinese Communist Party is looking to crackdown on these rights defense lawyers and activists?

EP: No. No, we should not be surprised. I don’t think that the lawyers are surprised either. And I say this, although I just said that initially, in the 1990s, there was this official promotion of and use of the idea of rights defense. There was, I think, for a couple of years, especially around 2003 when you had the famous Sun Zhigang incident, this notion that perhaps rights defense could mean a bold group of courageous lawyers, legal professionals, and legal academics sympathizing with them, persuading the State to introduce incremental reforms. One of [these reforms], for instance, could have been to introduce some sort of meaningful constitutional adjudication — whichever mechanism one would have used — this would have made a potentially very great contribution towards making constitutional rights guarantees more effective in actual people’s lives and actual legal practice in China.

So, [until around 2003] you had that hope — and of course along with that an expectation — that the State would tolerate weiquan. But actually very early on, from the moment almost when they started being successful, these weiquan lawyers also encountered repression. I think we now understand better than perhaps a couple of years ago, that that was really based in a high-level perception that weiquan presented a political challenge and that consequently, it had to be controlled.

So, what has been happening from about 2004 and especially over the past couple of years, has been a tightening of control, and the use of ways of trying to stop lawyers from engaging in weiquan. I don’t think that anyone I have spoken to has been surprised by what has happened.

EL: So in terms of the tightening of control, you mention that the Sun Zhigang case in 2003 is kind of a high point. But then by

2009, we see a government crackdown with Gao Zhisheng basically being abducted and being held incommunicado. Also in 2009, you see the disbarment of activist lawyers like Tang Jitian and Liu Wei; you see Xu Zhiyong being investigated. Then in 2011, with the Arab Spring, we see another crackdown. Now, 2013, 2014, we are seeing perhaps the worst treatment of advocates. So you were talking about how some of the responses [to weiquan lawyers] is coming from high-level. I think a lot of people see these different crackdowns as separate incidents, just a knee-jerk reaction by the Chinese Communist Party. But should we see it that way or should we see it as part of a larger trend?

EP: I think that it is based in a decision that as I just said was essentially made in 2004 that they would have to be controlled and I think that basic attitude and policy has remained the same also before and after the recent changes in leadership. So I definitely think this is part of a larger trend, yes. I think that also the situation at the moment is worsening.

EL: I think we can guess what it that the Chinese government is so afraid of. But what precisely is it? Is it the issues themselves or is it another power base that could take away power from the Party? What is it that they are so afraid of?

EP: Well, I think from the perspective of the Chinese authorities, or at least from [the perspective of] that part of the Chinese government that is entrusted with the task of stability preservation – of weiwen [维稳], it’s quite clear (and perhaps it is clearer to them than to lots of people outside and inside China) that the human rights movement of which human rights lawyers are of course an important part, stands for political ideas that challenge the Party’s political existence.

There is a perception also amongst the establishment that the current system isn’t viable unless it’s somehow changed. But I think what leads to this attitude of having to crack down on human rights lawyers is that the establishment, the authorities, are completely reluctant to allow any civil society forces to take control of the changes that need to be introduced. So, yes, there may have to be changes; but certainly we, the Party-State, want to stay in control of changes. Another way of putting the same thing, I suppose, is to say that the tizhinei [体制内]forces, the system, the establishment, can’t accept the idea of accountability to people outside of the system; and in a way, it is not institutionally set up to accept that idea. That of course means that the notion, the idea of political opposition, the idea of a free open political discussion of popular grievances, of the forces of social unrest, of the various contentious issues which you have in Chinese society right now is even less acceptable.

***************************************************************************************************************

For Part 2 of this three-part interview series with Prof. Pils, please click here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email