The Sentencing of Jiang Tianyong: What it Means for China & the World

Civil rights activist, Jiang Tianyong, sitting in the courtroom awaiting his sentence on Nov. 21, 2017

Last month, and three months after civil rights activist Jiang Tianyong pled guilty to “inciting subversion of state power,” the Changsha Intermediate Court finally issued its sentence: two years in prison (much of it already served) and the deprivation of Jiang’s political rights for three years.

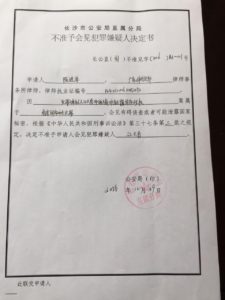

As far as the crime of subverting state power goes, a crime the Chinese government has increasingly used to silence its civil rights activists, things could have been worse. Jiang is seen as a leader in China’s civil rights circles, a lawyer who has daringly taken on some of China’s most politically sensitive cases, such as representing Falun Gong practitioners as well as ethnic Tibetans in the aftermath of the 2008 Tibetan riots. As a result of his zealous advocacy in these cases, in 2009, the Chinese government denied the renewal of his law license. But lack of a law license did not stopped Jiang from continuing his work. Ironically, much of his advocacy began to focus on a new vulnerable group: China’s civil rights lawyers. In 2011, Jiang played an active role in ensuring that blind activist Chen Guangcheng’s cruel house arrest remained in the public eye. More recently, Jiang was important in supporting many of his colleagues who were caught up in the Chinese government’s July 9, 2015 nationwide crackdown on over 200 civil rights lawyers and activists (“709 Crackdown”). Through blog posts, tweets, calls for protests and interviews with foreign media as well as with Philip Alston, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Jiang effectively kept the 709 Crackdown visible. It is this type of ardent support for his colleagues that has made him the him the soul of the movement.

Civil rights lawyer Zhou Shifeng at his sentencing. August 4, 2016

And in a legal system where the Chinese government essentially determines the crime and sentence of any activist regardless of evidence, such a leadership role would result in a charge that could lead to a substantial prison term. But Jiang was only charged with – and pled guilty to – the lowest level of subversion under Article 105 of China’s Criminal Law: inciting subversion of state power; a crime that carries a prison term of three years maximum. Some of Jiang’s colleagues – those caught up in the 709 Crackdown – received harsher sentences for actually subverting state power under Article 105, not just inciting it: Zhou Shifeng received seven years, Hu Shigen seven and a half years. And more recently, two other activists, Lee Ming-che and Peng Yuhua, both arrested after the 709 Crackdown but still part of the Chinese government’s attack on free speech, were each charged with – and pled guilty – to Article 105’s subversion of state power and were sentenced to five years and seven years, respectively.

Jiang Tianyong, second from left, and proudly standing with other activists outside of a detention center.

But make no mistake, Jiang has suffered just as much as these other activists while in detention. According to the China Human Rights Lawyer Concern Group, Jiang was repeatedly denied access to his own lawyers and allegations of torture have emerged. He was demonized in the state-run press and social media outlets, and, although his own lawyers could never gain access to Jiang, the state-run CCTV was able to interview him in which he “admitted” to fabricating allegations of torture of his colleague Xie Yang. After being held incommunicado for over nine months and under who knows what kinds of conditions, on August 22, 2017, Jiang pled guilty to the crime of inciting subversion. In his televised, in-court confession, Jiang called upon his fellow rights defenders and rights lawyers to learn from his experiences. A shockingly far cry from Jiang’s Twitter description – “A lawyer who was born at just the right time; a lawyer who’s willing to take any case; a lawyer hated by a small political clique; a lawyer who wants to win the respect of regular folk; a lawyer who kept going even after being stripped of his law license.” (translation courtesy of China Change) – causing many, including his wife, to strongly believe that his confession was forced.

Cultural Revolution Poster: “Imperialists and reactionaries are all paper tigers”

Although much of Jiang’s ordeal calls into question the Chinese government’s commitment to the rule of law, respect for human rights and why it must continue to abuse its own people, another deeply troubling trend has emerged: the Chinese government’s anti-foreign rhetoric. In reporting on the Jiang’s sentencing last month, the state-run Legal Daily blamed the “foreign, anti-China” forces influencing Jiang for much of his behavior. It is that paranoia of anything foreign that is the most dangerous to the current world order. With the U.S. retreating from its position of global, moral leader, China is seeking to rise and promote its type of leadership. From the trial of Jiang Tianyong, that moral leadership model seeks to create societies that are not just unresponsive to its own people, but shut off from connections with the rest of the world. But it is those connections between cultures and people that have long been a driving force of the post-WWII model and have helped to maintain the peace in much of the world these last 75 years.

But in blaming these elusive, foreign, anti-China forces, the Chinese government ignores the real reason why these civil rights activists exist: the injustices in Chinese society. It is Jiang’s own life that is a testament as to why the Chinese government’s efforts to suppress these civil rights activists will ultimately fail. For a long time Jiang was just an ordinary guy; after graduating from college, Jiang was a teacher for almost 10 years. But in 2004, wanting to pursue greater justice for others, he gave up teaching to become a civil rights lawyer, passing the bar exam in 2005. People like Jiang are not motivated by foreign forces or other entities; they are motivated to correct the injustices and sufferings of others to make their society better. The Chinese government cannot stop people from feeling that way and the real question is – why would they want to.

But in blaming these elusive, foreign, anti-China forces, the Chinese government ignores the real reason why these civil rights activists exist: the injustices in Chinese society. It is Jiang’s own life that is a testament as to why the Chinese government’s efforts to suppress these civil rights activists will ultimately fail. For a long time Jiang was just an ordinary guy; after graduating from college, Jiang was a teacher for almost 10 years. But in 2004, wanting to pursue greater justice for others, he gave up teaching to become a civil rights lawyer, passing the bar exam in 2005. People like Jiang are not motivated by foreign forces or other entities; they are motivated to correct the injustices and sufferings of others to make their society better. The Chinese government cannot stop people from feeling that way and the real question is – why would they want to.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

But, starting with the

But, starting with the