What is Up with Chen Guangcheng?

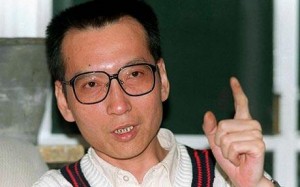

Chen Guangcheng, entering a Beijing Hospital with US Ambassaor Gary Locke and State Dep't Legal Advisor Harold Koh

More often than not, I am my friends’ go-to China person; something in the news pops up with China, I get the questions. So I wasn’t surprised on Saturday when over some carrot cake at the Chelsea Market a friend of mine had questions about Chen Guangcheng: if he cared so much about human rights in China, why would he leave? What is up with the Chinese government, keeping a blind man trapped in his own home? How did things get so messy between the U.S. government and Chen?

It’s been almost a month since Chen fled the home that illegally became his prison. So what exactly is up with Chen’s escape and to answer some questions – what does it all mean?

Chen’s Escape Has Propelled Human Rights to the Top of the US-China Agenda

My friend’s question on Saturday caught me off guard – does Chen really care about human rights in China if he fled to the protection of the U.S. Embassy, ostensibly to seek asylum and leave China.

To ask a man with a wife and two children to be a martyr for his cause is asking too much. As this blog has recounted previously, since Chen’s release from prison (oddly convicted of a traffic disturbance) did not result in freedom. Instead, for the past year and a half, Chen and his family have been subjected to illegal house arrest and at times, physical torture by his captures.

It is true that by departing China, Chen’s ability to change China’s current system will be much reduced if not extinguished. But his heroic flight has perhaps done more to highlight the Chinese government’s recent illegal oppression of dissent than anything else. Over the past year and a half, this blog has increasingly written about the Chinese government’s crackdown on China’s nascent rights defending (weiquan) lawyers. Aside from people already interested in the issues, these posts – and the acts of repression which they have focused on – have received little attention.

Chen’s escape and his subsequent stay at the U.S. Embassy altered this focus. With Hillary Clinton arriving for the Strategic and Economic

Dialogue (S&ED), the focus of U.S.-China relations shifted to human rights. For one week, as the world watched, the U.S. and China’s relationship was thrown back to a 1980s-Cold War paradigm, when ideology played a more governing role. For one week, the Western media’s attention finally focused on the repression of rights defending lawyers, and the lip service the Chinese government gives “rule of law” when it comes to civil rights and civil liberties.

It is amazing that a single man’s act, that one blind man’s heroic act, can still change the dialogue in U.S.-China relations. It is a hopeful reminder that in this globalized world, individuals still matter; that one man’s quest for freedom is still “news.” And don’t think Chen’s act was not a heroic one. Not only was a blind man able to find his way to Beijing, but imagine if he wasn’t; imagine if he was caught. Likely his fate would match that of Gao Zhisheng, a rights defending lawyer who, while in government custody, remains missing.

The U.S. Government’s Actions Supported Human Rights

Some have criticized the U.S. government – or more aptly, the Obama Administration – for its dealings with the Chinese government over Chen. Initially, the U.S. Embassy worked out a deal with the Chinese government whereby Chen would stay in China, study law at a university in a coastal city away from the thugs of his hometown, and be left alone with his family. This was what Chen initially wanted.

But once he left the safety of the embassy for a Beijing hospital, Chen began to reconsider his options. As Prof. Jerome A. Cohen recounted to CNN, the promised U.S. Embassy official was unable to stay with Chen at the hospital and once he began speaking other rights defending lawyers – friends he hadn’t been able to speak to for a year – he began to more clearly understand the increased oppression of rights defending lawyers in China. Chen was scared; Chen realized that without full information, he misjudged the situation. That’s when he vocally requested that he be able to leave China for the United States.

Were some in the U.S. Embassy a touch too naive to rely on the Chinese government’s promises? Most likely. But being naive is not the same as turning one’s back to human rights. It was Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s decision to allow Chen into the U.S. Embassy in the first place. Chinese citizens cannot just willy-nilly enter the U.S. Embassy; even American citizens are allowed limited access to their embassy (which resembles a high-security prison). As the N.Y. Times has recounted, embassy officials were notified of Chen’s flight to Beijing and on April 25, Secretary Clinton gave the authorization to sneak Chen into the embassy compound. Secretary Clinton knew full well that by providing that approval, a throw-down with the Chinese government on the issue of human rights was certain and the ultimate outcome unclear. It is unfortunate – although not all together shocking given the current acrimonious status of politics – that Washington D.C. cannot view this moment as a proud one for America and its ideals; that the web of support that both parties have built for a human rights network in China over the years enabled Chen to come to our door. Instead, it appears that what could otherwise be a proud moment for Americans, is becoming a political tug-of-war.

Who is Driving the Bus? The Chinese Central Government’s Lack of Control

What is perhaps the most shocking of all from this whole situation is the Chinese central government’s lack of control of local governments. Chen’s persecution has largely been conducted by the local government in his hometown, with local government officials still seething after his attempt to bring a lawsuit against them for forced abortions. But even when Chen fled to Beijing, his safety could not be guaranteed, hence his changed desire to leave for the United States. Many of his relatives left in their villages are being persecuted by local officials. It makes one wonder – who really drives the bus in China?

Imagine a United States where Governor George Wallace could ignore federal law, have his way and continue segregation in his home state of Alabama. Likely you can’t. It’s unfathomable to think that a national government is unable to enforce its own laws, and in the case of China, that a supposed authoritarian dictatorship cannot control lower level party members.

Chen’s case reflects a center weaker than anyone previously thought. And that is what is most frightening and should give people pause. Does China really have the power to become a rising superpower or will it revert to its warlord past, where each city is governed by its own power broker and the central government remains impotent?

While China’s weakness appears to manifest itself often in human rights issues, it should not be just a concern for human rights advocates. Anyone working in or with China – business people, government officials – should be troubled. A weak center, especially as China undergoes an important leadership transition this year, does not bode well for China.

Prof. Jerome Cohen – The Fixer

On a final note, I want to focus on Prof. Jerome Cohen and his role in all of this. As a research fellow for two years, I had the privilege of working

with Prof. Cohen at NYU’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute. In that time, I got to know a kind, brilliant man who never ceased to amaze me. It was Prof. Cohen who first identified the ingenuity and necessity of Chen’s unschooled, “barefoot lawyer” approach in 2003 and deservedly catapulted him to the world stage.

While my two years with Prof. Cohen were filled with inspiring moments, I have never been more proud of him than I was with his handling of the Chen Guangcheng situation. While this is all purely based on hearsay, it appears that it was Prof. Cohen who got the U.S. and China out of what was becoming a crisis situation. Prof. Cohen’s lifetime of experience with China, including high-level delegations soon after Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, allowed him to realize that all that was needed was a practical solution where everyone could save face: a scholarship for Chen to study law at NYU’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute and invitation for his wife and children to join him.

Now we wait and see. The United States has approved Chen’s visa application and just yesterday he applied for his Chinese passport. Although the Chinese government could renege on the deal, that looks increasingly less likely and ultimately not in their best interest. It’s never a satisfying moment when one of your citizens essentially seeks protection from a foreign government for human rights abuses, but on some level, the Chinese government is likely happy that Chen, who has long been a rabble rouser and a cause célèbre for other Chinese rights defenders and foreign friends, is leaving the country. Unfortunately for Chen and his family, he will likely never be able to return to his home country.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email