25 Years After Tiananmen – Same, Same But Different

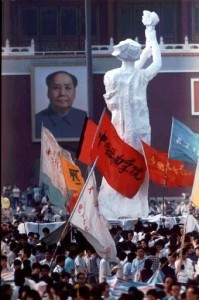

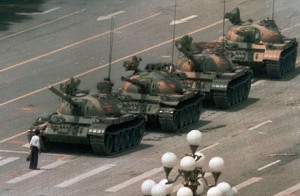

Twenty-five years ago, on the night of June 3 and into the early morning hours of June 4, 1989, tanks rolled in to the streets of Beijing and the Chinese government did the unthinkable: it opened fire on its own people, killing hundreds if not thousands of unarmed civilians in the streets surrounding Tiananmen Square. That violent crackdown marked the end of seven weeks of student-led, peaceful protests in the Square itself, protests that were supported by much of the rest of Beijing, protests that would amass hundreds of thousands of people a day, protests that people wistfully thought would change China.

Twenty-five years later the students who participated in the protests are no longer fresh-faced, wide-eyed college kids, the workers who supported them are retired, and many of the bicycle rickshaw drivers who ferried dying students to hospitals on that bloody Sunday morning are long gone. Along Chang’An Avenue, glitzy buildings have replaced the blood and bullet holes. Starbucks stand near where students once went on hunger strikes. Tiananmen is different; China is different. But yet there are some things that remain the same.

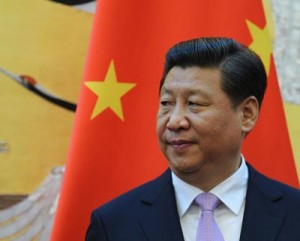

The government that ordered the crackdown 25 years ago – the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) – is still in power and many of the gripes that initiated the student protests – corruption and nepotism among political elites, lack of personal freedoms, and government censorship – have only gotten worse and continue to be the impetuous for activists. And, like the students in 1989, these activists are still willing to risk their lives to promote the values enshrined in the Chinese Constitution and guide China to become a better place for its people.

But make no mistake, while these factors might be the same, there are important aspects of China that have changed. In

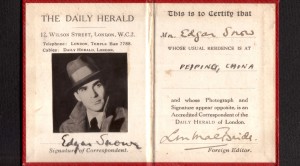

Hundreds of thousands of Beijing residents – students, workers, ordinary people – supported the protests.

particular, China’s rise as a global power. Criticizing China for human rights violations and its failure to live up to its own laws is not as easy as it was in 1989 when President George H.W. Bush cut off government ties, military relations, and the sale of U.S. government goods the day after the Chinese government’s crackdown. Imagine denying U.S. businesses the opportunity to sell products to the world’s second largest economy? That would never happen today. And to severe relations with China – would the American public want to so easily give up its cheap Walmart goods or be denied the ability to obtain the newest iPhone? Probably not. The Chinese government understands the soothing and influential comforts of our material desires.

But perhaps the most troublesome change is how the CCP now deals with dissent. If the last few months are any guide, excessive violence continues to be the modus operandi of the CCP. Cao Shunli (pronounced Ts-ow Shoon-lee), an activist who organized small, peaceful protests that called for citizen participation in China’s United Nations human rights review, was detained for “picking quarrels and causing trouble,” was denied medical treatment for months, and died in police custody. Tang Jitian (pronounced Tang Jee tee-an), a disbarred-lawyer-now-activist that sought to assist Falun Gong practitioners, has recounted the physical torture he suffered while in police custody in March. Since coming out of detention with 16 broken ribs, Tang has all but effectively been denied appropriate medical care for his tuberculosis which has gotten significantly worse.

But the CCP has learned from its mistakes. No longer is its violence against dissent as public as it was the morning of June 4, 1989. And no longer does the CCP come off as a lawless regime. Instead, its cloaks its crackdowns with a veneer of legality. Since April 2014, in preparation for the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, the Chinese government has detained – either criminally or through unofficial house arrest – over 84 individuals. But these individuals are not detained under the guise of being counter revolutionaries like the students of the 1989 movement. That would be too obvious. Instead, the Chinese government has slapped the vague and overly broad crime of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles.” After 20 years of Western rule of law programs, the CCP has come to realize that the easiest way to deflect global criticism is to follow legal procedure, no matter how abusive, vague or entrapping that legal procedure might be.

If the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen means anything, China’s new strategy – the use of law to suppress dissent – must be

examined and criticized. China’s activists are being violently detained and imprisoned in record numbers “in accordance with the law.” But that suppression of dissent is no different than what happened in 1989. It is another method of killing the chicken to scare the monkeys – ensuring that the violence against a few “troublemakers” teaches the rest of society not to rock the boat. This time though the rest of the world is increasingly complacent.

As the world marks the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre on Wednesday, China will be the lone nation that will not. Since 1989, its people have been forbidden to commemorate the event; they are not permitted to remember; they are not allowed to note those fateful days that changed their lives more than anything in China’s recent past. And that is why the events that other nations hold in honor of the many brave Chinese people who lost their lives on that night are so important. Because while the Chinese government has found new strategies to more effectively deal with international criticism of its treatment of its people, the one thing that the outside world still has is the truth. But that truth must not be limited to just what happened 25 years ago; it must also be used to call on China today stop its suppression of dissent today. To do otherwise is a disservice the victims of that night.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email