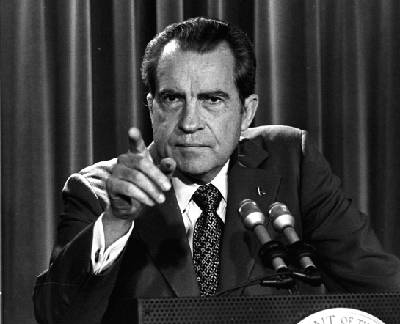

President Donald J. Trump (courtesy of whitehouse.gov)

For years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was in denial about the extent of its air pollution problem, often referring to smog-infested days as perfect “blue sky” ones. Then, in July 2008, @BeijingAir, a U.S. Embassy-created twitter account, began tweeting accurate pollution data throughout the day. Beijing was furious, claiming sole legal authority to monitor and publish air quality numbers. But the U.S. Embassy stood its ground, and slowly, the CCP began to acknowledge that pollution levels were dangerously high. By January 2013, the Beijing government began reporting accurate, hourly data and by the end of 2013, climate change, pollution levels, and green technology had become important parts of the CCP’s platform.

Fast forward four years, and it is now the United States that is censoring tweets about climate change. Instead of the transparency that has long been a bedrock of the United States’ political system and that we encourage in other, less democratic nations, President Donald Trump appeared to take a page from the CCP’s playbook: he ordered that the Badlands National Parks remove tweets about increased CO2 omissions and climate change, statements he disagrees with.

In fact, in much of the first week of Donald Trump’s presidency, the parallels to authoritarian regimes, specifically the CCP, have become all too real. It has become clear that Trump is not going to be the rational businessman that people had hoped for; he is not going to surround himself with advisers who temper his rash decisions. That is not how authoritarian leaders behave.

Upending Society – Trump, America’s Mao Zedong?

Chairman Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong came to power as a revolutionary, a populist and as a man intent on turning over the old world order. Those tendencies – among other things – help to explain why China was enveloped in disarray for most of Mao’s 27-year reign. Similarly, these are the same impulses found in Trump, his campaign and thus far his presidency, as noted China scholar Orville Schell pointed out two weeks ago at an Asia Society event. Trump’s preeminent goal is not necessarily to advance the United States economically or even to advocate a coherent, ideological policy platform; rather his motivating impulse is to upset the current world order: “I think there is a bit of an outsider, troublemaker, turner-over of old orders, putting fingers in the eyes of the establishment in Donald Trump” Schell noted.

It is the disarray and the upending of society that appeals to Trump. “If you don’t destroy, you can’t construct” was a favorite saying of Mao as he took China on the pointless path of a continuous revolution. Understanding that aspect of Trump is important in figuring out how to deal with his presidency. Appealing to economic logic when he calls for a 20% tariff on Mexican goods and calling on American values when he institutes a ban on Muslim immigration is not going to resonate with Trump.

Projects That Are Ideological, Not Beneficial

Rural residents and victims of China’s Great Leap Forward

Part of an authoritarian regime is the dedication to ideological-based projects, even at the expense of economic or social progress. For Mao, the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) stands out. In order to prove that China had made the “great leap” to an industrialized, rich, communist society, Mao ordered the complete collectivization of farms, factories, and most of society. Harebrained ideas of digging crops deeper, smelting steel in backyard furnaces, and building useless irrigation projects, resulted in one of the greatest man-made famines in history. Within a year, the leadership knew that the program was a failure. But the CCP ignored this fact and continued the campaign, committed to the ideological line.

In his first week, Trump has already called for an ideological project that most agree will hurt America more than it will help: building a wall between the United States and Mexico. But most undocumented immigrants over-stay their legally-obtained visa, not walk across the border. Trump ignores this fact and instead has proposed building a border wall that will cost between $10 billion (Trump’s estimate) and $38 billion (MIT’s estimate) and distract America from dealing with more compelling issues. While he demands Mexico pay for the wall, the only proposal Trump has offered is a 20% tariff on Mexican goods, a tariff that will likely be borne by the American consumer.

Some of the wall that already exists between Mexico and the U.S. (courtesy of NBC News)

Because the emphasis is on ideology and not practicality, ideological projects are neither particularly well-thought out nor properly executed. During the Great Leap Forward, Mao decided that China would double its steel production. To meet this goal, Mao instituted “backyard furnaces:” every item made of metal – doorknobs, farm tools – was smelted down. But as Mao would find out, smelted down metal produces inferior quality pig iron that cannot be used, let alone sold abroad as steel.

Similarly, Trump’s January 27, 2017 executive order, to ban immigration of Muslims from certain countries, gave no thought to its legality or to its implementation. Signed after 4 pm on a Friday and to take immediate effect, the world was left unprepared. Immigration officials, who had no prior notice of the precise contents of the executive order, were left largely in the dark, and when refugees, green card and visa holders arrived, chaos ensued.

But logical arguments and exposing impracticalities are likely not going to cause Trump to change his mind. His campaigns are about ideology and like Mao, expect Trump to double down when confronted with facts and the failure of their implementation. Much like he did on his twitter feed on Monday regarding Friday’s executive order.

Of Purges & Sycophants

As part of his purge, Liu Shaoqi, was often publicly criticized during the Cultural Revolution

From Mao to Xi Jinping (pronounced See Gin-ping), Chinese politics have been roiled with political purges. It is a way for the current leader to eliminate threats to his power, maintain his authoritarian control and ensure that those remaining quickly fall in line. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Mao purged Liu Shaoqi (pronouced Leo Shao-chi) and Deng Xiaoping, two senior officials who had gained support among the Party for their economic reforms. Liu eventually died in prison but Deng was able to survive, and in the early 1990s, implemented those economic reforms that caused Liu his life.

Current President Xi Jinping has also purged those he considered a threat to his rule, using the Party-controlled legal system to do so. In 2012, photogenic, ambitious and popular politician Bo Xilai (pronounced Bwo See-lie), long considered competition to Xi and his power base, was arrested and tried on charges of corruption, receiving a life sentence. In 2015, Zhou Yangkang (pronounced Joe Yongkong), the former head of China’s powerful Ministry of Public Security and a supporter of Bo, received the same fate. A life sentence in a Chinese jail is a good way to eliminate perceived rivals

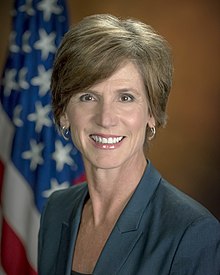

Former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates

Under Trump’s rule, New Jersey governor Chris Christie was the first to go, even before Trump officially took office. While the reason is unclear, some saying his son-in-law didn’t get along with Christie while others maintaining that Christie’s honest advice was too much for Trump, it wasn’t the most practical move to remove the head of your transition team – and all of his staff – in the midst of executing the transition plan.

But on Monday, Trump carried out his first purge of his Administration: the firing of Acting Attorney General Sally Yates who, like the courts, questioned the legality of his executive order and called on the Justice Department staff to decline to defend it. Reminiscent of CCP use of inflammatory rhetoric for its purges, Trump issued a similar factional statement, stating Yates’ “betrayal” of the Justice Department and that she is “weak on borders and very weak on illegal immigration.”

But these purges are not just about eliminating threats and consolidating power, it is also to ensure that those remaining toe the party line. Before the Great Leap Forward, Premier Zhou Enlai (pronounced Joe N-lie) had fallen out of Mao’s favor. Desperate to get back in his graces, Zhou became an ardent supporter of Mao’s Great Leap Forward even though he quickly became aware that the program was a failure with hundreds of thousands starving to death. But, fearful of a purge, Zhou never revealed the truth to Mao, afraid to challenge him. Instead, Zhou remained committed to the program and ordered that Mao’s irrational demands be fulfilled: that China immediately pay off its international debt through grain export.

Pence and Mattis watch Trump sign Friday’s executive order.

Most Republicans did not speak out against Friday’s executive order that essentially banned Muslims from a select list of countries from legally entering the United States. Even those who had previously condemned Trump’s call for a for a Muslim ban – Vice President Mike Pence, Speaker Paul Ryan, newly appointed Secretary of Defense James Mattis – have yet to utter a word. But speaking up may mean falling out of Trump’s favor. And like Zhou Enlai before them, they appear to prioritize their position in Trump’s inner circle over everything else.

This is why Trump’s cabinet appointees’ statements to the Senate – that climate change is real, that water boarding is torture – cannot necessarily be relied upon. Once in office, will they be like Pence and Mattis, willing to fall in line with Trump’s extreme views and carry out his orders? And now that Trump has appointed Steve Bannon, his chief strategist, confidant and heretofore intelligence novice, to the National Security Council, while simultaneously downgrading the director of national intelligence and the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff to a need to know basis, is Trump messaging to his cabinet that ideology takes precedent over expertise – that in red versus expert, red wins?

Attack on the Press

Press Secretary Sean Spicer on January 21, 2017 discussing the size of the crowds at Trump’s inauguration (courtesy Getty Images)

Calling the press “the opposition party,” lecturing reporters on what they “should be writing,” referring to journalists as “the most dishonest human beings on earth,” are all a part of the Trump Administration’s strategy on how to interact with the media, or more aptly, how to crush it. Eerily, it is also the strategy of the CCP, in its efforts to ensure that freedom of the press never takes hold in China: “the ultimate goal of advocating the West’s view of the media is to hawk the principle of abstract and absolute freedom of the press, oppose the Party’s leadership in the media, and gouge an opening through which to infiltrate our ideology” (translation of the CCP’s Document No. 9 courtesy of Chinafile).

With its attacks on the media, the question remains just how far the Trump Administration will go in trying to clamp down on the press. The CCP offers a frighteningly effective alternative, with its arrest and prosecution of journalists on trumped up charges, its random detention of reporters critical of the government, its toying of the visa process – and for some outright repulsion from China – for foreign journalists when the CCP does not approve of their coverage of China.

But even in light of the Trump Administration’s censure, the U.S. press continues to try to serve its role as a watchdog of the government. But if the Trump Administration steps up its campaign against the press à la the CCP, who is going to win that battle?

(courtesy of China Digital Times)

Creating a Ministry of Truth

Throughout his campaign and now, in the first week of his Administration, Trump has been accused of telling lies and at times, trying to censor the truth. But alternative realities are nothing new to an authoritarian regime. The Chinese government is a master at it. Referring to hazardous pollution as mere fog? Trying to hide from your people and the world that SARS is spreading and hitting epidemic proportions? Blaming the recent downturn in the economy on mysterious foreign forces? Having web pages just disappear? All alternative realities that the CCP uses to maintain its authoritarian control.

Insisting that your inauguration crowd was larger than President Barak Obama’s when the pictures clearly depict otherwise? Pretending that your executive order is not a ban on Muslim immigration? Claiming that you lost the popular vote because millions of people voted illegally? Having web pages just disappear? These are all alternative realities the Trump Administration has offered in just the past week alone.

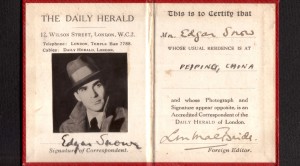

Lies and alternative realities come with a real danger – that people will start to believe them or will never know the truth. Take for example the Chinese government’s censorship of the its violent crackdown in 1989 on the students protesting in Tian’anmen Square. For the first few years after the Tiananmen massacre, the question was, how long will the Chinese government refuse to investigate the government-sponsored murder of hundreds of Chinese students. Twenty-eight years later, the question now is, will the Chinese ever know their own history? Most below the age of 30 have never seen the photo of “tank man” let alone have any idea about what happened on that fateful night in June 1989.

Conclusion

Protests erupt on Saturday at San Francisco International airport (courtesy of AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez)

To be clear, America is not China. This is not how things have to progress nor necessarily how they will. But what we see with the Trump Administration is a start. And even a start is dangerous. But at the same time, many of America’s most revered democratic institution – the courts, its lawyers, the media, the American people – have spontaneously stood up to try to protect this country and its people.

But for the past week, Congress has been too slow to realize that the Trump government is no ordinary administration: this is a president and an administration that in its first week in power is more reminiscent of an authoritarian regime than a democratic one. The ordinary tactics of politics – the give and take, the horse trading – are not going to suffice; bolder steps need to be taken. Like the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, politicians need to constantly and publicly pressure and oppose the Administration if they want to ensure that America stays true to her democratic ideals.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email