Hold the Champagne: The Bo Xilai Affair, the Party-State, and the Rule of Law

by Glenn D. Tiffert

Part 2 of a two-part series on the Bo Xilai Affair. Click here for Part 1.

With its personal and political dramas, and its broader implications for leadership succession, the Bo Xilai Affair (“the Affair”) has captivated observers of the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”). But beneath the headlines, the Affair affords an opportunity to take stock of the evolving relationship between the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) and the PRC state, a task this post briefly undertakes in the context of discipline and punishment.

Although China today largely has a market economy, the Leninist political concept of the “Party-state” remains a useful one. The term suggests a duality in which each component maintains a distinctive identity amid mutual, deep entanglements.

According to one recent description: “The Party is like God. He is everywhere.”Its tendrils penetrate every corner of Chinese political, economic,

Vladamir Lenin: His Ghost Still Lives on in the Chinese Party State

social, religious and cultural life, and it tolerates no organization it cannot monitor or control. Hence, in principle, every institution of significance in China has internal Party representation that links to a parallel, external hierarchy of Party organs. This arrangement is intended to maintain the Party’s intimacy with Chinese society and leadership of it, and facilitate tight discipline over ideology as well as policy formation and implementation.

Yet, the boundaries and terms of the Party-state duality are far from stable. Historically, they have generated fierce contestation and fluctuated widely, not just in the PRC, but also under the Nationalist regime that preceded it. In short, Party and state, though tightly entwined, variously face one another in tension.

The Bo Xilai Affair illustrates the ongoing complexities of the Party-state relationship well, particularly as it pertains to the legal system. To explore this more concretely, let us reconstruct from the public record the differential handling and case procedural histories of the Affair’s principal players –Bo, his wife Gu Kailai, and Chongqing police chief, Wang Lijun.

A Tangled Web: Discipline Through Both Legal and Party Means

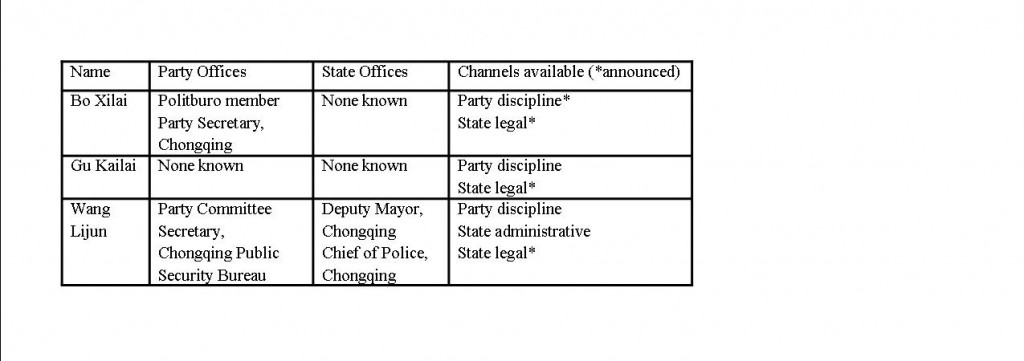

Generally speaking, the PRC maintains three official channels of discipline and punishment for government officials and Party members. These channels may overlap or intersect in specific cases.

The first channel involves ordinary criminal liability. All citizens accused of crimes – including officials and Party members – are subject to the state legal system familiarly comprised of police, procuratorates and courts. But, Article 74 of the PRC Constitution exempts deputies to the National People’s Congress (“NPC”) from arrest or criminal trial without the consent of the NPC Presidium or its Standing Committee. At the time the Affair erupted, both Bo and Wang were NPC deputies.

The second channel, also governed by state law, involves administrative sanctions and applies specifically to government officials and Party members, who are subject to a thicket of regulations and laws enforced by an assortment of agencies, including the Law on Public Servants and, in complex or serious cases, investigation and sanction by agents of the Ministry of Supervision pursuant to the Administrative Supervision Law.

The third and final channel exists in parallel to the state legal system and is purely Party. Under the Party Constitution and subsidiary rules and regulations, CCP members are subject to Party discipline. In fact, the CCP maintains a hierarchy of internal Discipline Inspection Commissions charged with investigating both concrete cases and maintaining the overall organizational and ideological health of the Party.

Attempt to Separate Legal Liability and Party Discipline

Deng Xiaoping takes power in China and the early 1980s sees "reform & opening"

When the CCP began reconstructing its state legal and internal disciplinary organs in the early 1980s after the disruption of the Cultural Revolution, an effort was made to assert their separateness. Thus, the Party’s Central Discipline Inspection Commission and Organization Department jointly opined in 1982 that CCP members could be arrested and tried in the state legal system under the criminal law without first waiting for the Party to dispose of their cases internally, and that the Party disciplinary process could even begin after a judicial verdict. They added that punishment under the criminal law should, with limited exceptions, result in expulsion from the Party. Indeed Article 38 of the Party Constitution declares in part that “Party members who seriously violate the criminal law must be expelled from the Party.”

Very little public information is available on the operation of the Party disciplinary process, but observable practice indicates that this stab at separation did not get very far. Although the 1982 Party Opinions intended to loosen the chains that bind the state legal process to the Party disciplinary process, in practice, the Party exercises a right of first refusal towards suspected criminals within its ranks. Accordingly, Party officials suspected of offenses prosecutable under the criminal law are routinely held to account only through internal disciplinary channels, where anecdotal evidence suggests they often get off more leniently than the criminal law would allow – in many cases effectively suffering no more than setbacks to their careers. This amounts to a double standard of justice for Party members and understandably outrages those who believe that everyone in China should be equal before the law.

It appears that the Party countenances prosecution by state judicial authorities only of members suspected of especially serious or notorious crimes, crimes that in its estimation cry out for punishments heavier than mere internal Party discipline, or in which the Party wishes to set a public example. Consistent with its 1982 Opinions, the Party may in these instances allow the police and procuratorate to originate a case in the state legal system, or it may refer a case to them after exhausting its own internal disciplinary process. Of course, the latter – in which the Party has already made its own internal decision – effectively constitutes a form of political guidance on the expected outcome of the state criminal prosecution and trial.

In addition, because police and procuratorial personnel often participate in Party disciplinary investigations, they are familiar with the details of the referred case before it formally enters the judicial process. What is more, at the time of referral, the Party forwards to them the report of its Discipline Inspection Commission and the official findings therein. Thus, the Party disciplinary process – even though it appears on paper as separate from the legal system – contaminates the judicial process at multiple points, making independent adjudication that much more difficult.

the referred case before it formally enters the judicial process. What is more, at the time of referral, the Party forwards to them the report of its Discipline Inspection Commission and the official findings therein. Thus, the Party disciplinary process – even though it appears on paper as separate from the legal system – contaminates the judicial process at multiple points, making independent adjudication that much more difficult.

How Does the Party-State Discipline Model Play Out in the Bo Xilai Affair?

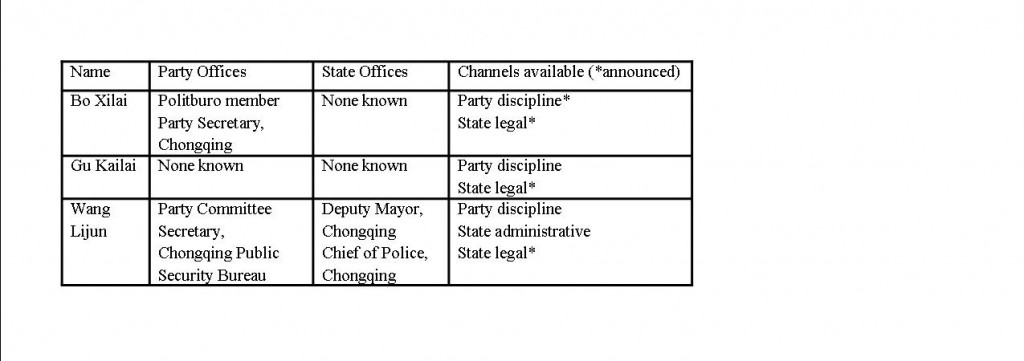

How do these arrangements bear on the Bo Xilai Affair? The three principals – Bo Xilai, his wife Gu Kailai, and Wang Lijun – were all members of the CCP. So far as we know, Gu Kailai held no Party or state offices, but Wang Lijun held both, and Bo Xilai held Party, but no state, office. As the table below indicates, these facts determined the channels through which their cases publicly traveled.

– The Case of Bo Xilai

The Party’s handling of Bo Xilai exemplifies a classic sequence of discipline and punishment for Party members: (1) suspension of Party posts pending the results of disciplinary investigation, (2) expulsion from the Party upon the completion of that investigation, (3) seamless referral to the state judicial system for prosecution and, eventually, (4) conviction. The key outstanding questions concerns the specific charges that will be leveled against Bo and the severity of his ultimate sentence.

Bo Xilai

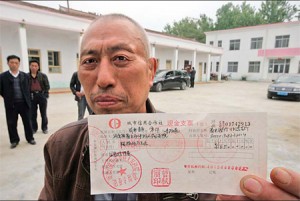

Deconstructing his case further, as a member of the Politburo, Bo fell directly under the Party jurisdiction of the Central Committee. Thus, on March 15, 2012 and pursuant to the Party’s internal Regulations on Disciplinary Punishment (中国共产党纪律处分条例), the Central Committee removed him from his Chongqing Party posts, chief among them Party Secretary. Further following the sequence mentioned in the prior paragraph, on April 10, 2012 the Party suspended his membership in the Politburo and the Central Committee and announced that his case would be sent to the Central Discipline Inspection Commission (CDIC) for investigation of “serious disciplinary violations.” On September 28, 2012, after considering the CDIC report on his case, the Politburo of the Central Committee expelled Bo from the Party and referred him to judicial authorities for prosecution. Divested of his Party membership, on September 29, 2012, Chongqing municipal authorities formally requested that the National People’s Congress (NPC) strip Bo of his seat (and the immunity it conferred) in order to formally clear the way for prosecution. As of this writing, we await the trial and sentence.

Another outstanding question concerns Bo’s whereabouts since his last public appearance in mid-March. As a subject of Party investigation, he was likely held under shuanggui (双规), an extra-legal form of detention used by the Party in its disciplinary process to investigate and interrogate members suspected of violating Party rules or state law. Party rules restrict shuanggui to a term of six months, which coincides well with Bo’s mid-March disappearance. We may learn at trial that he was transferred to state custody on a date that falls plausibly within this six-month time limit.

– The Case of Wang Lijun

Wang Lijun’s case traveled a different route. On February 7, 2012, Wang left the United States Consulate in Chengdu and surrendered

Wang Lijun

immediately to central authorities, reportedly from the Ministry of State Security, disappearing from view until his trial in mid-September. However, Wang was not formally arrested by State Security until July 22, 2012, having been stripped of his NPC seat and the immunity it conferred several weeks before, on June 30.

Authorities have offered no public account of his whereabouts between early February and late July. Three possibilities suggest themselves. First, in China, the police can detain an individual for investigation in a detention center or jail without arrest for up to 37 days, though they may be able to reset that clock and lawfully extend detention further by tacking on charges with strategic timing. A five and a half month detention, however, would have stretched that to the point of unlawfulness and, while hardly unprecedented, the intra-Party stakes would arguably have made the Party averse to tainting its handling of this case with that kind of procedural irregularity.

A second, more remote, possibility is the extra-legal Party form of detention called shuanggui, discussed above. Third, Wang may have been placed under “residential surveillance (监视居住),” a controversial form of prolonged detention famously used against government critics that, contrary to its connotations, is frequently served at a place or facility designated by the police. Under the Criminal Procedure Law, residential surveillance is limited to a period of six months, which fits Wang’s disappearance from public closely.

Gu Kailai

– The Case of Gu Kailai

Gu Kailai’s detention raises the same questions. She disappeared from public view in mid-March, was not formally arrested until July 6, 2012 and reappeared only at her trial for the intentional killing of Neil Heywood on August 9, 2012. Nearly four months separated her disappearance and arrest, and again the official record offers no explanation. Investigatory detention for that length of time for a single charge of homicide too would have been unlawful.

Foregrounding the State: CCP Reticence in the Gu & Wang Cases

Wang and Gu were both Party members, but interestingly the Party has only spoken of their cases in the context of the state legal system; it has studiously avoided associating them with its internal disciplinary process. This would favor residential surveillance, rather than shuanggui, as the explanation for their extended disappearances.

The Party’s inhibitions about connecting these two cases to discipline manifests in another important way as well. Wang and Gu have both been convicted of “serious” crimes, but no public announcement of Party disciplinary sanctions, most obviously expulsion, has followed; Article 38 of the Party Constitution requires expulsion.

In the past, such announcements routinely arrived at the outset of the state legal process. The practice of announcing expulsion just prior to referring the case to judicial authorities suggested a convention that Party members in good standing were immune from state prosecution, irrespective of the 1982 Opinions. Bo Xilai’s case, for example, conforms to this model, as did those of Chen Xitong and Chen Liangyu before him. There are signs, however, that this practice has changed, at least for some defendants.

For cases like Gu’s and Wang’s, which originate in the state legal system rather than with a disciplinary investigation, the Party is no longer consistently publicizing the disciplinary consequences of conviction. One might read this as a positive development if it indicates that the Party has rediscovered the spirit of the 1982 Opinions and is again loosening the chains that bind the state legal system to its internal disciplinary process. After all, given the clarity of the Party Constitution on the consequences of conviction for serious crimes, one may assume with good reason that Wang and Gu have been, or will be, expelled. On the other hand, with public faith in the capacity of the CCP to police its own at a nadir, continued silence on their standing in the Party, especially in light of their notoriety, invites cynicism and conspiratorial theorizing.

Discipline Through the Administrative Channel: Greater Rule of Law by the Party?

In addition to the Party disciplinary and state criminal processes discussed so far, there remains another channel: the state administrative process. A dizzying array of state administrative organs regulate malfeasance by government agencies and their personnel. The relation of these various administrative organs to one another and to the Party disciplinary process is not always clear, though one example stands out from the pack and demonstrates how intertwined the state administrative disciplinary process is with the Party’s.

Historically, the crowning organs of the state administrative and Party disciplinary channels have had overlapping memberships, with key cadres concurrently holding leadership positions in both. For example, the current Minister of State Supervision, Ma Wen, also serves as a Deputy

The Downfall of Bo Xilai begins with the Party

Secretary of the Party’s Central Discipline Inspection Commission, just as her predecessor, Qian Ying, did in the 1950s, when Qian established the precedent. In fact, the correspondence between these organs extends deeper still: in 1993, the Central Discipline Inspection Commission actually absorbed the Ministry of State Supervision in a merger, and while they remain distinct on organization charts, their twin apparatuses often function as alter-egos in concrete cases.

Strictly speaking, only one of the three defendants held state office at the time the Bo Xilai Affair erupted, Wang Lijun, and I will have more to say about him in a moment. But in a curious twist emblematic of the overlap between Party and state, Bo Xilai himself is also subject to the 2005 Law on Public Servants (公务员法), paradoxically through his Party status.

In 2006, the CCP Central Committee and State Council, as the top organs of Party and state administration, jointly issued an Implementation Plan for the PRC Law on Public Servants(中华人民共和国公务员法实施方案) (“the Plan”). The Plan makes clear that, pursuant to subsidiary Rules on the Scope of Public Servants (公务员范围规定) (“the Rules”), functionaries in CCP organs (工作人员), with the exception of service workers (工勤人员), qualify as public servants and thus are subject to the Law on Public Servants; Hence Party officials who hold no state office are now counter-intuitively subject to state law regulating public servants.

Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Rules is still more explicit, listing among the categories of CCP personnel included within the scope of public servants “leading personnel of Party Committees and Discipline Inspection Commissions at the central and various local levels.” Under this rubric, Bo Xilai, as Chongqing Party Secretary and a member of the Politburo qualified doubly, and hence the announcement of his referral for prosecution properly lists the state Law on Public Servants among the legal bases for the Party’s decisions to remove him from his Party posts.

The optimistic reading of this convoluted logic would go something like this: the Party, having conceded that it is subject to the law, faithfully submits its leading members to the same regulatory standard as state public servants, a refreshing acknowledgment perhaps of their actual powers and functions amid the blurred boundaries of the dualist Party-state.

But before we break out the champagne to celebrate this milestone in the tortuous journey of the rule of law in China, it bears keeping in mind that while such maneuvers reference state law, they reach it only after an initial, internal determination by the Party; it is the Party that permits a case to attain this point.

But before we break out the champagne to celebrate this milestone in the tortuous journey of the rule of law in China, it bears keeping in mind that while such maneuvers reference state law, they reach it only after an initial, internal determination by the Party; it is the Party that permits a case to attain this point.

Moreover, a further cautionary note underscores how provisional the change is in the relationship between Party and the state. Though the Party has gone to considerable lengths to present its handling of the Bo, Wang and Gu cases as procedurally unimpeachable models of socialist rule of law, certain details belie its tidy narrative, and Wang Lijun helps to show how.

Recall that of the three defendants discussed here, only Wang is known to have held state office at the time the Affair erupted. On March 26, 2009, the Chongqing Municipal People’s Congress, acting under its constitutional authority, appointed him Chongqing Police Chief, and on May 27, 2011, it elevated him to serve concurrently as Deputy Mayor. The power to reassign or dismiss Wang from these posts similarly fell under its jurisdiction.

Nevertheless, Wang’s February 2, 2012 reassignment from police duties, the event that precipitated his flight to the United States Consulate several days later, was not in fact ordered by the People’s Congress or by another legally authorized state body, but by the city’s Party Committee, controlled by Bo Xilai. This unlawful conflation of Party and state – where the Party performs duties reserved to the state – was then compounded on March 15, 2012, when the CCP Central Committee, via its Organization Department, removed Wang from his position as Deputy Mayor. It was not until March 23, 2012, that the Chongqing Municipal People’s Congress formalized Wang’s dismissals from these posts, making them legally valid. For as long as fifty revealing days, the gaps between Party and state, power and law, brazenly lay bare.

Party authorities, at both the municipal and national levels, in their haste could not be troubled to maintain appearances by first arranging Wang’s dismissals through regular state channels. Instead, the Party violated the Constitution and other laws, thereby poking holes in the self-congratulatory, socialist rule of law banner it attempted to wrap around these cases. In short, Wang’s case reminds us that even after considerable effort to systematize Party and state administration and bring the Party under the ambit of state law, old Leninist habits and sensibilities remain alive and well, and are never far from the surface.

While I like the Godfather movies as much as the next person, it’s always strange when personal vendettas make it onto the world stage. But that is what appears to have happened on Monday when the Chinese government failed to renew New York Times reporter, Chris Buckley’s journalist visa before it expired on December 31, 2012.

While I like the Godfather movies as much as the next person, it’s always strange when personal vendettas make it onto the world stage. But that is what appears to have happened on Monday when the Chinese government failed to renew New York Times reporter, Chris Buckley’s journalist visa before it expired on December 31, 2012. which details the growing inequalities in China, has been waiting for accreditation from Beijing. If Higgins’ situation is a guide, Pan should not hold his breath.

transparency to our political system. In a one-party authoritarian country, that transparency can only be provided by the foreign press. The United States spends millions of dollars of “rule of law” and democracy projects in China. But supporting the work of foreign correspondents in China, at least verbally, is equally as important a tool to achieve those goals. As we noted in our July series, it is imperative that the U.S. government publicly address and admonish the Chinese government’s attempt to censor the foreign press through the visa renewal process.

transparency to our political system. In a one-party authoritarian country, that transparency can only be provided by the foreign press. The United States spends millions of dollars of “rule of law” and democracy projects in China. But supporting the work of foreign correspondents in China, at least verbally, is equally as important a tool to achieve those goals. As we noted in our July series, it is imperative that the U.S. government publicly address and admonish the Chinese government’s attempt to censor the foreign press through the visa renewal process. On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email