China Law Translate’s founder Jeremy Daum

In the past ten years, the number of Chinese-speaking foreign scholars of Chinese law has increased dramatically, and the number of Chinese lawyers who speak and read English has increased even more. Inevitably, this raises the question of whether translations of Chinese legal materials are still necessary and likewise for American laws translated into Chinese.?

For Jeremy Daum, the creator of China Law Translate (www.chinalawtranslate.com) and Senior Research Fellow at the Yale China Law Center in Beijing, a community-based translation website, the answer is yes, and more so now than ever. China Law Translate (“CLT”) uses internet resources and a volunteer army of netizens to translate various legal documents – laws, regulations, articles, interpretations and news stories from Chinese into English and vice versa.

Over the last two years the site has become an important resource as foreign interest in Chinese law continues to grow. Cited by the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the United States Congress, China Law Translate is a novel attempt at crowd-sourced collaboration for this kind of translation. To understand its success and impact, China Law & Policy interviewed CLT founder Jeremy Daum to better understand the site and its planned future.

[In the interest of full disclosure, China Law & Policy is a proud participant of China Law Translate’s community translation project.]

************************************************************************************

EL: What caused you to create China Law Translate?

JD: Pure selfishness–I use our translations constantly.

In creating the site, I had three goals. First, to allow experts, students and other interested folks to contribute their time and efforts without making a big commitment. At the same time, I hoped to incorporate technological tools to make translation easier. Finally, I also wanted to create a forum for discussing the accuracy of the translations, so our group could begin to standardize commonly used, but uniquely Chinese legal terms.

Also, while it sounds hokey, I honestly believe that communication leads to increased understanding, and hope that

China Law Translate – making it as easy to translate like pushing a button!

the site helps contribute something to foreign legal professionals’ understanding China’s situation and vice versa.

In 2013 when I started the site, there were a number of major new laws and interpretations released, not the least of which was the revised Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) with its 290 articles, the Supreme People’s Court’s accompanying 548-article interpretation, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate’s accompanying 708-article interpretation and the Ministry of Public Security’s 376-article implementation regulations. That’s a lot right there, and even reading through it can take an enormous amount of time.

There are a lot of us translating various documents, but we too often translate the same work, duplicating efforts constantly but rarely sharing the successes in any meaningful way.

EL: In introducing this interview I mentioned that with the increased number of bilingual experts, translation might be less relevant. The positive response to your site indicates that you aren’t alone in valuing translation—so, why is translation still important?

China Law Translate’s mascot, Judge Bao, a general in 1000 AD but also a symbol of justice.

JD: It’s a legitimate question, but I suspect that anyone who has ever practiced or studied law in China knows that language can still be a barrier. Translating legal texts requires a big skill set- not just excellent language ability, but also an understanding of both the Chinese and foreign legal systems. Law itself is already a kind of second language, and ensuring accurate communication across national languages and legal systems is not so easy.

The number of foreign nationals and organizations involved in China is still increasing, and they all have a practical need to understand Chinese law. At the same time, Chinese law is becoming more and more sophisticated, and this also makes translation more important. Where a quick summary might once have been enough to get a feel for the law, it is now necessary to actually parse the text and follow through to read its interpretations, local implementing regulations and so on. If China’s ongoing legal reforms are to be taken seriously, you have to understand what they really say.

EL: Your site has been used by the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. Congress. Have you been surprised by the response to your site?

JD: Well, we get fairly steady traffic of readers despite slow service times behind the firewall, but only about 1% of visitors have ever even opened the translation panel to contribute. Still, that the media and various governments find the translations useful means we are making a contribution.

One thing that has surprised me is the percentage of readers who are Chinese speakers coming to read Chinese

If only this guy had come to China Law Translate first! This tattoo means “Chicken Noodle Soup”

language materials. That is to say, about 20% of the traffic is people in China, with their computer set to Chinese, reading Chinese law in Chinese. Sometimes when you set out to solve one problem you end up meeting another need entirely. My only guess as to what’s going on is that other online versions of Chinese laws just aren’t as searchable as ours are—they are often divided up into several pages and you can’t just search the text easily. We always talk about access to law—well, the site seems to be accidentally helping some Chinese people access their laws.

EL: What have been the most important or most cited translations?

JD: I sometimes say that instead of “China Law Translate” the site should be called “China Law Translated”, because in addition to straight translations, we do also provide explanations, commentaries and a real-time newsfeed. These include blog posts and original articles by me, (and anyone else who wants to submit) and also annotations made through a great comment system called Factlink that lets people make sidebar comments on specific chunks of a law.

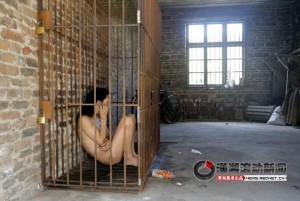

So, some our most heavily trafficked pages have been translations of draft laws that other places aren’t likely to bother translating: The draft domestic violence law and the draft counter-terrorism law have both been among the site’s busiest pages. Others have been original pieces like an explanation I wrote about the crime of provocation (“ picking quarrels”) a poorly understood offense that has been used to detain a number of prominent activists. We’ve also had a lot of traffic on important case documents of interest to a wider foreign audience, such as the verdict of Xu Zhiyong.

EL: What’s the benefit of CLT’s translations over more formal and traditional processes, like a law school hiring a translator?

Don’t get lost in translation!

JD: I love it when law schools, NGOs, governments etc. hire translators to create reliable bilingual versions of laws and documents to share with everyone. It just doesn’t happen very often. Translation is expensive, and usually still requires expert staff time to review if quality is to be assured, so its takes time on top of the translation fees. We avoid a lot of that by working together.

Also, those few translations that are shared publicly aren’t usually kept in a single location where everyone can find them all. But CLT isn’t just a repository for translations either, it’s truly collaborative. Once something is online, it keeps evolving, getting better through contributors comments and additions.

Finally, there are a few pay services that put out translations of key documents, but the pay wall limits the number of people who can use them, and honestly, I think we match them for quality. More importantly, they tend to cater to a different audience, focusing on documents involving business and transactional law, rather than the public law materials CLT emphasizes.

EL: Just to explain it to those who may not have ever seen the site, how exactly does it work?

JD: The documents on the site are broken into single sentence units of meaning for translation purposes. When you open the translation/editor mode, you can click on any of these translation units to make changes, and after you approve the change, it changes the way everyone coming to the site sees that translation.

Even if you don’t want to make changes, you can also use the translation mode to compare the translation to the original language. In reading through translations, I’ve found that I generally see at least one typo that I want to correct, so I encourage others to do this too.

On the off chance that vandals come through and change all the text of the translations, a record is kept of every change to every block of text, and they can be rolled back without any heartache.

EL: If you start translating a law, do you have to finish it? What’s the time commitment for your volunteers?

Not a big time commitment

JD: There is no minimum or maximum time commitment; it’s an ad-hoc ongoing collaboration. And there is certainly no need to finish a translation in one sitting – many of the translations on the site are works in progress, and any portions that haven’t been translated just get displayed in the original language.

It’s a funny thing, I made the site precisely because nobody has time to translate everything by themself, but lots of colleagues still say they’d love to contribute if they only had the time. My thought is this, if you are looking for a certain part of a law, check our site, see if we have it and if that part of the law has been translated yet. If not, translate it so it’s there for the next person.

If you are really devoted, you could translate a random sentence or two a day, it’s a great way to practice language skills!

EL: What if someone who does a translation wants credit for it? Are you willing to allow that person’s name to appear on the translation?

JD: As long as you log in to the site, any translations you make are attributed to you, and anyone who looks at the translation history of a given translation block will see what you did. Most people seem to want NOT to be detected, and translate anonymously by not logging in.

If someone submits a completed full-text translation, I’m happy to put it up with their name (or logo) clearly indicated and an explanation that they submitted it. I do like to keep the entire site editable, so I would probably also put up a PDF of the document as originally submitted so that nobody would wrongly attribute any subsequent changes to the donor.

For folks who consider themselves active members of our community, we have a system where frequent users earn points for visiting the site and commenting and can earn badges or even t-shirts. Of course, if a regular participant wants to put their CLT participation on their resume or what have you, I’d be happy to vouch for them.

EL: How do you guarantee accuracy?

JD: Oh, hah, I don’t. We do our best, and I’ve corrected a few obvious mistakes more than once, but at least at CLT every reader can correct mistakes they see.

As I mentioned above, the secondary goal of the site, beyond creating translations, is creating a forum for discussing translations. There’s room for disagreement about what terms mean even between native speakers discussing their own language’s legal terminology, and it only gets worse when you start translating.

If something on the site seems wrong or bizarre, bring it up in the comments and see if others have something to contribute. This is a conversation that needs to be happening for the benefit of both Chinese and English speaking users.

EL: China Law Translate has been around for a little over two years. Where do you see it going in the future?

JD: In addition to trying to expand our translator and editor base, I’m trying to encourage other organizations doing translations to let me cross post their content. I know that lots of groups do translations for a meeting or case that they only use once, maybe not realizing the value that these documents have for a wider audience. This is just one more way to make the site more complete and collaborative.

EL: Well, thank you again Jeremy first off for creating such an amazing resource and this interview. In case any of our readers are inspired by this interview, they should go to www.chinalawtranslate.com, right?

JD: Yes! Go to China Law Translate to translate your first sentence today!

To help get you started, here is the intro video that guides you in how to translate on China Law Translate:

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email