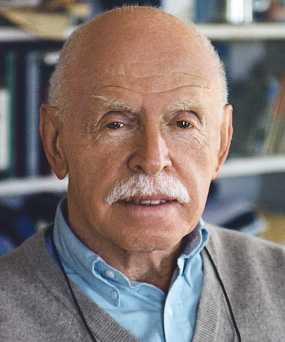

Jerome A. Cohen – An Essay for His 90th Birthday

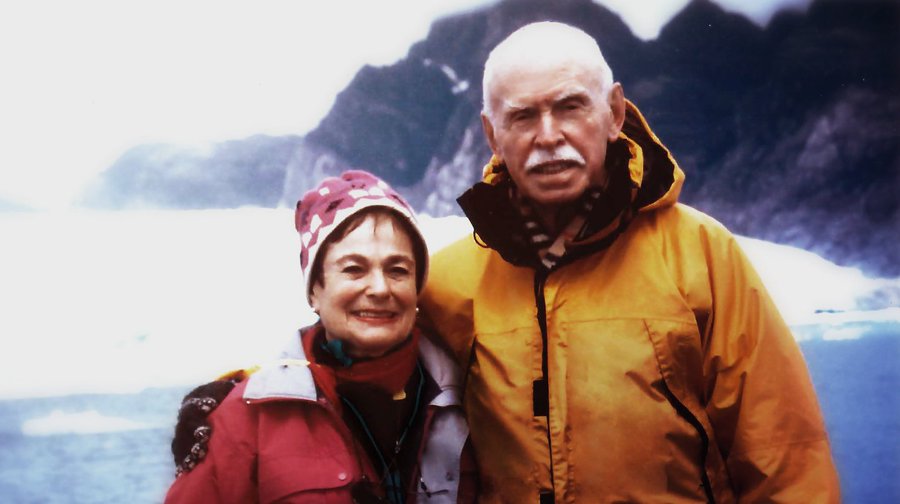

It was my first trip to Taiwan and I was traveling with a celebrity, Jerome A. Cohen. I had started working for Jerry at NYU Law School’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute only a few weeks prior. Because it was August, I hadn’t seen much of my new boss who was spending the summer in Cape Cod. Taiwan would be my first opportunity to get to know Jerry, one of the pre-eminent scholars of Chinese law in the West.

As soon as we arrived in Taiwan, Jerry’s importance in the region was evident. At the airport, we were picked up in a car befitting a high-level dignitary. We dined with then-Vice President of Taiwan, Annette Lu, a former student of Jerry’s and who, in 1985, Jerry helped secure an early release from a 12 year prison sentence for her political speech. And wherever we went, people asked Jerry about another of his former students, Ma Ying-jeou, a presidential candidate who would eventually win. This law professor from New York had the ear of the highest level of Taiwan’s politics.

Jerry’s high-level contacts didn’t stop at politics. We also met with Justice Lai In-jaw, the recently appointed President of Taiwan’s Judicial Yuan, in other words, the chief justice of Taiwan’s highest court. He too had been a student of Jerry’s. For over an hour, Justice Lai and Jerry discussed recent legal changes in Taiwan and Justice Lai expressed his excitement about his new position leading the Court.

At the end of the meeting, when we had already stood up to show ourselves out, Justice Lai stopped us, turned to Jerry, and, after noting that Jerry had clerked for Chief Justice Earl Warren in the 1950s, asked in a hushed, solemn tone “Do you have any advice for me in my new position?”

Jerry paused, looked at Justice Lai and asked “Have you ever watched The Graduate?” The seriousness on Justice Lai’s face quickly disappeared with his eyes opening wide. A smile spread across his face and in a voice louder than I expected said “Yes! Mrs. Robinson! The Sound of Silence!”

Evidently Justice Lai was a fan of the flick. But I wondered, where is Jerry going with this; how could The Graduate, a movie from the 1960s where a mother seduces her daughter’s boyfriend, provide guidance to the future president of Taiwan’s Judicial Yuan. Jerry continued. “Do you remember the first scene, the pool party?” “Yes!” Judge Lai exclaimed. “Do you remember when Dustin Hoffman asks his dad’s friend, ‘what should I do?’ And the friend says ‘Plastics. Get into plastics.’” Judge Lai, still smiling, nodded repeatedly. Jerry looked at Justice Lai and with a smile said “So Justice Lai, get into plastics!” On that note, our meeting was over and I thought, what have I gotten myself into?

What I got myself into was the start of a relationship that would change my life and shape the way I see China, the world and the pursuit of justice. When I started working with Jerry back in 2007, he was in the thick of supporting China’s human rights (weiquan) lawyers. But unlike other academics, he didn’t just study these lawyers. He met with them. He supported them. He advocated for them before high-level Chinese officials. Jerry took on the cause of these human rights lawyers, recognizing that they were as much change agents as those in power. Often it was through Jerry that their stories of persecution were kept alive in the West. Jerry’s unwavering belief that rights lawyers are necessary to rectify societal injustices rubbed off on me. When, two and half years later, I was offered the opportunity to take a job with a legal services organization in New York City, I spoke with Jerry before making a decision. I was torn. Should I abandon the study of Chinese law for a public interest law job in the U.S.? Jerry didn’t hesitate. “Yes” he told me. But that’s Jerry, always encouraging you to take a risk and sometimes knowing you better than you know yourself.

The last time I saw Jerry before New York City went into COVID lockdown was at a talk he was moderating about academic freedom in China. During the question and answer period, a middle-age professor from China raised his card to speak. When it was the professor’s turn, he began with an opinion that was contrarian and, as he continued to talk, the groans from other audience members were audible. Even I bristled at what seemed like the party line. The Chinese professor began to slow down, likely unsure if he should continue with all the eye rolls from the audience. But Jerry, looking directly at the Chinese professor, asked him to continue, telling the professor that he wanted to hear the professor’s on-the-ground experience. The professor resumed, a little more confident with Jerry’s encouragement. Jerry engaged the professor, asking pointed questions that developed what turned out to be an important and insightful perspective.

That moment is etched in my mind because it is so different from what we see in today’s society, where we are quick to stake a position and dismiss or objectify those whose opinions differ. But Jerry is not afraid to be challenged by a different opinion and he has the grace to engage those with different perspectives, making them comfortable to share their life experiences. We need to be more challenged. We need to be more respectful of each other. We need to be more like Jerry.

I also often think back to our meeting with Justice Lai where I first got to see Jerry’s mischievous side and learned that none of us should take ourselves too seriously; regardless of our age or where we are in life, we should continue to have fun.

So to Jerome A. Cohen, on this July 1, 2020, happy 90th birthday! May you continue to be the teacher we need now more than ever and may you have many more years of fun!

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email