Performance Review: Everybody is Gone – Capturing some of the horrors of Xinjiang

There was nothing ordinary about the ticket check. As soon as I approached the counter, the usual giddiness of seeing an opening night performance vanished. Separated from my friends, I was met with the angry scowl of a woman in a military uniform who took my ticket and barked at me: “Name!” “Elizabeth” I said. “Do you have singing talent!” “No.” “Do you have managerial experience!” “Yes.” With one last suspicious glare, the woman flicked my ticket back at me and shouted “go,” pointing in the direction of an open doorway. I sheepishly scurried to the next room.

Thus marked the beginning of Everybody is Gone, an immersive art performance that does an astonishing job at conveying a little bit of the horror of being Uyghur in China. Co-created by Uyghur artist Mukaddas Mijit and U.S. journalist Jessica Batke, Everybody is Gone just concluded its opening run last week in Berlin and hopefully will secure funding for future performances, including in the United States.

As the Chinese government seeks to push it’s authoritarian ways abroad, recently stating that the Taiwanese people need to be “re-educated” after Nancy Pelosi’s visit to the island, Everybody is Gone allows the audience to experience what “re-education” means in the Chinese context. Since 2017, the Chinese government has been using the term “re-education” to justify its mass human rights violations in the Uyghur autonomous region of Xinjiang: the internment of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims without any judicial process or legal basis; suppressing the Muslim religion, the dominant religion of Uyghurs and others in Xinjiang; criminalizing ties abroad; forcing Uyghur families to have a Han Chinese party member live with them; forcibly limiting Uyghur births; sending Uyghur children to boarding schools; and constant surveillance and use of algorithms to punish Uyghurs for essentially being Uyghur.

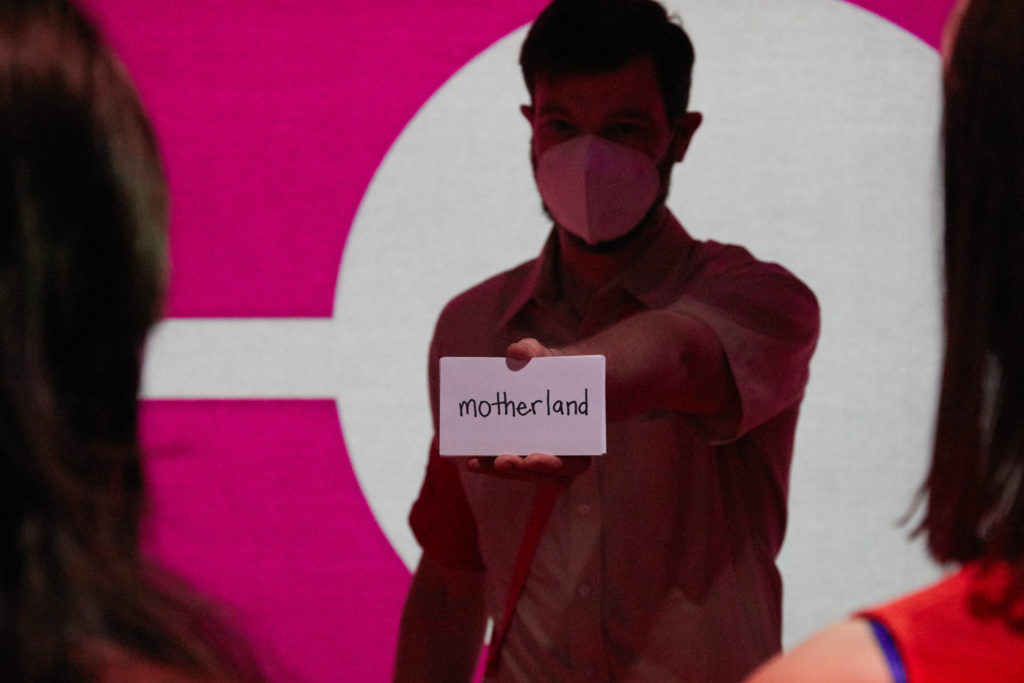

My re-education began when I entered the next room where I was met by another silent, angry guard who grunted at me to join a group in the far corner of the room. Lined up in two rows, audience members were commanded to provide definitions of words that the combat-boot-wearing guard held up on an index card. “You,” the guard hissed, pointing to the audience member standing next to me. “What does this word mean?” As I stood looking straight ahead, hoping not to be noticed, my neighbor mumbled some sort of inadequate response to the meaning of “motherland.” “Give me your ticket” shouted the guard, taking my neighbor’s ticket and scribbling something on it, then moving to another audience member – “You!” – demanding she define the word. After she gave a definition, the guard made my neighbor repeat it and then sent him off to another group. When one of my friends was asked to define the word “globalization,” she became tongued-tied even though she works in international banking. Should I help her? Or would that just make things worse? Similar thoughts raced through my mind when the guard suddenly turned to me and asked “did you come here with others.” Do I tell the truth? Or would that get my friends in trouble? But if I don’t tell the truth, wouldn’t they know?

How quickly the audience became paralyzed with fear is perhaps the most shocking part of the show, and about ourselves. Eye contact ceased. When an audience member was ordered to provide a false self-criticism, no one stood up to defend her. How to keep the guards pleased so as to avoid being pulled out for public humiliation became one’s primary focus. And while it may have just been a fluke that Everybody is Gone’s opening run was in Berlin, ultimately it was the perfect city to host what has been held to be an ongoing genocide of the Uyghur people. Berlin is filled with museums that explain the Nazi’s rise, the terror of living under such a regime and the horrors of the concentration camps. These tours take you to the places where the events happened, and by standing in these places, you try to imagine what it must of felt like and how, if you were in a similar position, would you survive. But with the ongoing crimes against humanity in Xinjiang, the world cannot go to where the crimes are being committed. Everybody is Gone bridges that gap a bit. Using leaked government documents of camp protocols and the testimony of Uyghur refugees who have escaped abroad, Everybody is Gone allows the audience to feel a little bit of the horror of living in Xinjiang right now.

The show ends with a village meeting, where the audience must sit there silently as Party chiefs drivel on about strengthening the motherland and attempt to make examples out of “good” audience members and “bad” ones. It is at this point where it becomes obvious that the nameless country of Everybody is Gone, with its hot pink flag, is China. As I sat there, exhausted from the tension of the last hour and hoping to avoid being dragged on to the stage, all I kept thinking was what a colossal waste of time and resources this indoctrination is. Instead of allowing people to go to work, raise their families, and find other ways to better themselves and society, they have to experience the stress of being part of a targeted group. And this doesn’t even capture the full extent of the psychological torture or even touch upon the physical torture of solitary confinement, forced sterilizations and other abusive methods going on in Xinjiang. After the live performance concluded, the screens on each side of the room filled with the faces and voices of Uyghur refugees, telling of the pain and misery they have endured. Some keep their faces hidden because if they show themselves, their family members still in Xinjiang will feel the repercussions. These testimonies can also be watched on Everybody is Gone’s informative website here. Also on the website is a database of reliable source material, including Chinese government documents, about the myriad human rights violations in Xinjiang.

Everybody is Gone is not for the faint of heart. It is a stressful hour-and-a-half and even though it only captures a little of what are Uyghurs experiencing, it is enough to remind the world that it must act to stop China’s genocide against the Uyghurs. In the beginning of 2022, the Chinese government’s crimes against humanity and genocide were filling headlines. With the war in Ukraine, the Brittney Griner situation, Taiwan tensions and other events, the news cycle has lost sight of what is happening in Xinjiang. But as Everybody is Gone reminds us, it is still ongoing; human beings are still suffering and the Chinese government is still trying to destroy a people.

On one of my last days in Berlin, as I walked with a friend, gold Hebrew lettering atop a building we were passing flickered in the afternoon sun. Not expecting to see Hebrew, I stopped to look more closely. We were in front of Berlin’s New Synagogue, one of the city’s few Jewish structures that survived Kristallnacht but whose congregation largely did not. On the front of the synagogue, was a plaque written in German but which ended with the phrase, all in caps, “VERGESST ES NIE.” My friend, looking at the plaque, said the German phrase aloud. I asked her what it meant. “Never forget” she said. Everybody is Gone takes these words seriously, forcing its audience to not forget what is happening Xinjiang and in doing so, demand that we act in time so that the Uyghurs do not experience the same fate of the New Synagogue’s members.

Rating:

Everybody is Gone ran in Berlin from July 27, 2022 to August 2, 2022. Currently, it has not posted any new shows as it was only funded for the seven-days in Berlin. We hope that it is able to find funding to continue. Check Everybody is Gone’s website for future announcements.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email