Red Gate Gallery’s founder, Brian Wallace

If you want to understand Chinese contemporary art, a conversation with Brian Wallace is a must. Although a humble man, much of China’s contemporary art field is a result of Wallace’s early efforts. In 1991, barely a decade into Deng Xiaoping’s dismantling of the socialist economic state and only two years after the Tian’anmen crackdown, Wallace opened China’s first contemporary art gallery, Red Gate Gallery. Housed in the infamous Dongbianmen Watchtower in Beijing, for the past 21 years, Red Gate has been a mainstay in the Chinese contemporary art field, identifying and promoting some of China’s best-known artists.

With its 21st anniversary and it’s current exhibit – 20th+1 where older, established Chinese contemporary artists identify some of China’s up-and-coming young artists – China Law & Policy sat down with Wallace to discuss the beginnings of China’s contemporary art movement, the impact of the hot art market on Chinese art and the future of the field.

Red Gate’s current exhibit – 20th+1 which identifies some of Chinese up-and-coming young artist – is only open for a few more days, until December 31, 2012. So if you want to see some great pieces, better high-tail it to Beijing’s Watchtower to check out Red Gate’s show.

Click here to listen to the audio of the interview with Red Gate Gallery’s founder, Brian Wallace

Length: 17:35 minutes (audio will open in a separate browser)

Click here to open a PDF of the transcript of the Brian Wallace Interview

*******************************************************************************************************************************

[01:00] EL: Thank you Brian for inviting us today. I want to start with the beginning and a simple question. Why? What made you think to open a contemporary art gallery in Beijing when no one else had? And what was it about 1991 that caused you to open it?

[01:14] BW: Thanks Liz. While I was at University here studying Chinese language, my Chinese friends were artists. So back in the ’80s I started to help them organize exhibitions at different venues around town. As you know there were no commercial galleries, no private galleries. So we had to hire different spaces and these turned out to be Ming dynasty buildings; structures like the Ancient Observatory – that is where I was doing shows in ’88 and ’89. But other groups of artists were organizing shows at the Temple of Longevity, the Temple of Law, the Confucian Testing Center and such places which were empty and in some cases in quite bad states of repair.

[02:02]But anyway we were able to use those places. So during those few years I got to know many of the artists and enjoyed helping them

One of the remaining vestiges of Beijing’s Ming Dynasty city walls, the Dongbianmen Watchtower. Since 1991 it has housed Red Gate Gallery.

while I was studying Chinese language at the same time.

[02:14] In 1989 everything stopped of course, so I went to the Central Academy of Fine Arts and did a bridging course in contemporary Chinese art history. Not that there was much of that at that time. Then in ’91, I’d been here for 5 years and was wondering what I was going to do – go back to Australia or look for a job. It made me think about what we had been doing and we thought we would try and open a gallery at the Observatory. So we went back there and they said no, but down the road was this Ming Dynasty Watchtower which had just been restored and was re-opening to the public. So they [the Observatory] gave us a very good introduction to the management here [at the Watchtower]. That’s how we opened Red Gate in 1991.

[03:00] EL: When you first opened the gallery, so you were already friends with the artists. But how did you, for the gallery purposes, did you have to choose between which artists’ works to show and how did you do that?

[03:14] BW: Well yes, I was friends with many artists but we wanted to work with a particular group so we just got them together. Our first show I think had about 7 artists.

[03:26] EL: And who were those artists in the first show?

[03:28] BW: There was Wang Luyan, Zhang Yajie, Da Gong, just to name a few.

[03:37] EL: And in terms of having a Westerner open a gallery here, how did the Chinese art field in general respond to your presence? Were they happy that have a gallery here interested in their work or were they confused as to what your goals were?

[03:54] BW: No because they knew me. And they also recognized that this was the first time someone was doing something like this so they were quite enthusiastic about being involved in it. And we all were supported by the very small foreign community, mainly diplomats, cultural attaches, students, a few business people who were around at that time. Many were very, very involved with the Chinese economy, the Chinese lifestyle, meeting Chinese, learning Chinese. So they were very interested in seeing this develop even though we were developing from nothing and learning from the ground up.

[04:40] EL: So it sounds like back in 1990-91, it was basically a group of artists and then a lot of Western support, supporting their work morally as opposed to financially. What about mainstream Chinese people?

[04:51] BW: The interest was very limited to the artists and that group of foreigners. Outside of that there was no interest whatsoever in contemporary Chinese art. People had plenty of other things they had to worry about before then. And they didn’t have any experience in going to galleries or understanding art.

[05:13] What we have seen over the last 20 years is a huge educational learning curve for everyone, not just Chinese but foreigners and Western supporters.

[05:26] EL: Let’s focus now on the shift in Chinese art. Back in 1991 it was pretty much a very small field. What in addition to having more mainstream Chinese people support Chinese contemporary art, what are some of the major changes you have seen in the past 21 years in Chinese contemporary art in addition to just the support and the prices?

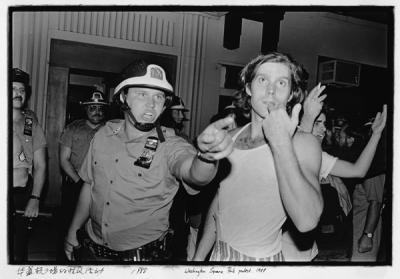

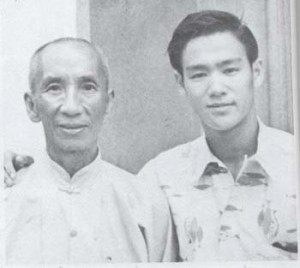

Yue Minjun, an early Chinese contemporary artist. This painting – Execution – sold for $5.9 million at auction in 2007.

[05:52] BW: Well, for the artists that I have been working with, if we want to talk about their message, it’s all been a very strong commentary on what has been going on around them because they have been part of this dramatic change. They have seen it from very much the inside. That first group of artists from the ’80s, early ’90s, they were all post-Cultural Revolution graduates and part of the first group that came out of the Universities after they re-opened. So they have seen a lot. Those people are in their 40s and 50s now. That generation of artists is one that I keep going back to. I’m not looking for that particular age group but it is that maturity in their work, that content.

[06:41] EL: So what kind of….the changes I guess from 1991, what do they paint now, what kind of work do they do now in terms of reflecting their environment?

[06:50] BW: Well, many of them are still working on the same subject matter and that could be anything from corruption, the environment, the state of living, freedom, things like that. Many, many topics that they talk about and comment on. Some of it is quite direct, some of it is very subtle. That’s their way of negotiating their particular environment here in China.

[07:24] EL: And what about the next generation that is coming up – the 20 and 30 year olds.

[07:29] BW: Part of our current show addresses that issue. The subtitle of the show is “Two Generations of Contemporary Art.” We ask the older [artists] or the artists who have been with Red Gate for 20 years to nominate someone who they have had their eye on who is very good.

China’s younger contemporary artists – when will they grow up?

[07:44] The problem with looking at that younger generation is that many of them are quite well-skilled but they’re not that creative; they’ve landed in the art scene at the time of the boom in the art market. Many of them have chosen being an artist as a career over being a doctor or a lawyer. That’s changing but that’s sort of breed a younger generation of people who were not that experienced, not very creative. So finding the very, very good ones among them has been a difficult task. Finding the strong ones, the independent ones, we’ve found a few over the last few years. But by having this particular show, all the artists we asked picked 10 very, very good [younger] artists. Some of them are quite young, some are in their 30s and even there are a couple in their 40s, but they are quite unknown in the art scene.

[08:43] So these nominators took their time and took this role very seriously because they knew people were going to see who they chose. We are very happy with the result.

[08:58] EL: Just to go back to some of the younger artists who have chosen this more as a career because of the boom in the art field. What do you think has caused the market for Chinese contemporary art to become so hot in the past 5 years?

[09:13] BW: The introduction of a lot of money from the domestic market. Just before that there was the international auction houses picking up a lot of Chinese artists from the secondary market and putting prices very, very high. That sort of led the way. And then very quickly followed by a cashed-up group of Chinese collectors but primarily investors who were looking for a quick return. They landed in that market at the right time and took advantage of it. Some of them did make a lot of money and lots of them had lots of fun.

[09:55] But now things have been dragging on since 2008. Things have settled down and a lot of those people have moved on as well. So there has been a maturing in that market.

[10:08] EL: Do you think that will be better for the younger artists to have less of this hot market?

[10:14] BW: Definitely. Some of them will move away completely from this career – if the money is not there, they are not that interested.

[10:28] EL: In terms of the art, Chinese contemporary art; what is it about it that makes it “Chinese?” Is it a continuation on a spectrum of

Traditional Chinese art techniques – brush painting.

Chinese art? I mean, I am very familiar with a lot of the more classical art pieces, the calligraphy. And then I see Chinese contemporary art and it doesn’t really look that “Chinese” to me. Should I even view it as something that should be on a historical perspective with traditional Chinese art?

[10:58] BW: That’s pretty hard. There are artists who are still using the traditional techniques in contemporary art. They are more or less proponents of maintaining those traditions but they’re using very contemporary content. Apart from that, there’s a whole range of media being used now and people are addressing issues which are to them individual. It is very much about where they are and where they are living – that’s China. But the issues are global. So people could come in and say, well some of the artists are talking about the environment and they would think that it could be back home. So that kind of thing, these issues are very, very global.

[11:52] What people see in this group of artists, these people in their 30s and 40s, they are surprised by it because their reference to Chinese art going back a few years was the more traditional: was the calligraphy, was the scholar rocks. So they are very surprised that over the last decade, the last 15 years there is this very vibrant contemporary scene. That’s what’s been a catalyst for their interest.

[12:27] EL: In terms of the art that is in the current exhibit, can we look at one of the pieces and maybe explain to somebody like me who knows little about modern art what about it that makes it a valuable piece of art.

[12:42] BW: Sure.

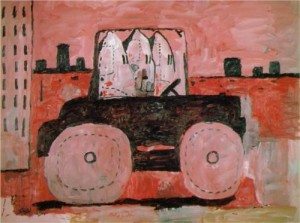

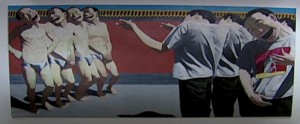

Chen Ke’s Red Sacred Mountain No. 6

Red Gate Gallery

[12:43] EL: I’ll let you choose one of the pieces. So which one are we going to look at here?

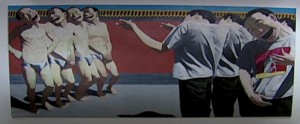

[12:50] BW: This is Chen Ke.

[12:52] EL: Okay, this is Chen Ke. What’s the name of the piece?

[12:54] BW: The name of the piece is Sacred Mountain No. 6, Red Sacred Mountain. He was one of the artists nominated by a senior artist in the gallery, by Wang Yuping in fact. Now apart from a wonderful piece of craftsmanship – very thick oil paint, the coloring all in red and shades of red, which is just quite striking. He is talking about, after 1949, new China. The future was bright, the future was red, communist red; everybody was working together. There was this unity and common purpose of all these people who were part of the new China.

[13:45] So you can see that in his painting that people are just having fun in the field; they probably had a long work day. They’re in their regular, probably nylon outfits, nylon white shirts that we used to see everywhere.

[14:01] What Chen Ke is talking about, he is looking at this nostalgic view about what things were happening in the ’50s, maybe early ’60s and comparing it with today and this dis-unity out there, this chaos in comparison to that previous time which was not so much a utopia but there was very much a common purpose in doing things. Here, today in contemporary China right now there’s not that unity.

[14:35] EL: Right, right, you have a growing disparity in wealth and interests. Are there any other pieces you want to talk about?

[14:44] BW: Well, we were talking about the environment earlier. There is Zhou Jirongover here who is from southern China but has lived in

Zhou Jirong’s Mirage

Red Gate Gallery

Beijing since he graduated back in the ’80s from the Central Academy of Fine Arts. His theme has always been about the environment. You can see this mixed media work is rather hazy.

[15:04] EL: What’s the title of this one?

[15:07] BW: Mirage. So on some of the days you look out the front door here…

[15:15] EL: It sort of looks like….

[15:16] BW: ….this is what you see, this is the landscape. And again, this could be anywhere in the world: a very polluted environment; a very quickly developing environment, uncontrolled.

[15:27] Then you have this other younger artist over here, Li Xiang from northern China with this very bare, barren landscape. Maybe the environment has been destroyed.

[15:50] EL: Just in terms of what else Red Gate is doing…you talked about how when you originally started Red Gate it was helping to foster the art community. How are you continuing to do that with the Artists in Residency programs. Can you talk a little bit more about those?

Li Xiang’s Night scene No. 3

Red Gate Gallery

[16:04] BW: We’ve been doing that for 11 years now. We invite artists from all over the world and inside China to come and work in Beijing in studios. They’re averaging about two months, sometimes three months. Most of them have never been to China before so they have to come through this cultural barrier landing which we help them with and get them to work as soon as they are ready.

[16:30] They might be working toward a show back home. Some of them, we are finding more and more, work their way into shows in Beijing – either group shows or have some solo shows or even become represented by galleries here. So they’re finding opportunities here of meeting other artists, that’s one of the main things, but also meeting curators and dealers and collectors from around the world who are all passing through Beijing. It’s something that they didn’t envisage and they realize that they may not of had that opportunity back home. So they find that that is another very rewarding side of the program for them.

[17:08] EL: And they also interact a lot with the Chinese art community?

[17:13] BW: Oh yes, very much. They are finding that they are not here by themselves, but there’s a large artist, foreign artists community, who are living here on a long-term basis, so they get to know those people.

[17:26] EL: Brian, this show – 20+1 – is on until December 31?

[17:34] BW: Yes.

[17:34] EL: Great. Thank you so much for your time and for teaching us about Chinese contemporary art.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email