Without A Tomb To Sweep: The Death of Liu Xiaobo

2010 Nobel Peace Prize recipient, Liu Xiaobo

This past Saturday, China Law & Policy marked the 8th anniversary of its founding. But a commemorative birthday piece seemed inappropriate with the news that a few days earlier China’s only Noble Peace Prize winner, Liu Xiaobo, died in police custody.

Since the founding of this blog, Liu Xiaobo has been in jail. His crime? His speech. And in examining the Chinese government’s cruel response to Liu’s death, it is this speech that this aspiring superpower continues to fear. Liu Xiaobo was not a murderer, a terrorist, and or even a revolutionary. He was merely a Chinese activist, academic and public intellectual that for close to 30 years, used his pen to call upon the Chinese government to live up to its commitment to human rights; a commitment that China has agreed to by signing on to certain international treaties; a commitment that was written into the amended Chinese Constitution in 2004.

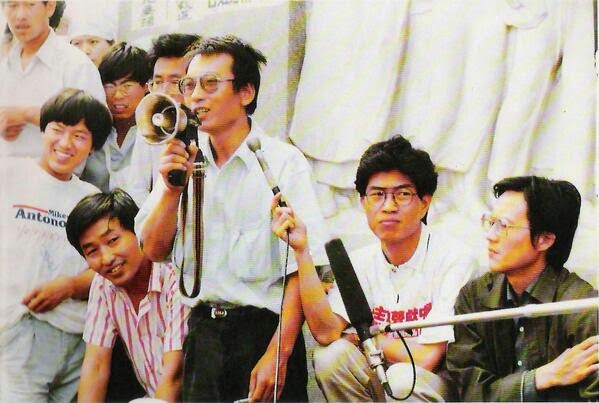

Liu’s most recent prison sentence wasn’t his first. In 1989, Liu, who came back to China from a prestigious fellowship at Columbia University to support the students in Tiananmen Square, was sentenced to almost two years in jail for partaking in the movement. When he was released, Liu lost his university position and his writings were

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square. Later, Liu would be credited with brokering a peace with the troops to allow the couple of hundred of students left on the Square on June 4 to leave without bloodshed.

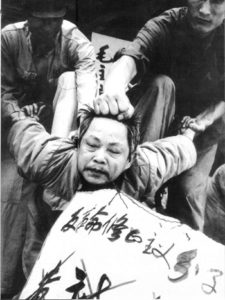

banned in China. In 1996 Liu was imprisoned for three years, this time in a Re-Education Through Labor camp, for a series of essays criticizing the Chinese government and calling for greater democracy for the Chinese people. Then, in late 2008, Liu co-drafted a document known as “Charter 08.” Modeled after Charter 77, the document that sparked the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, Charter 08, called for greater human rights in China, the end of one-party rule and an independent legal system. Nothing terribly revolutionary. But for that, Liu was arrested, tried for inciting subversion of state power and, on Christmas Day 2009, sentenced to a harsh term of 11 years. When he died last Thursday, Liu had only had about two years left on his sentence. He hadn’t been heard from since his 2009 conviction.

But the silencing of Liu Xiaobo for the past eight years was not enough for the current regime. When he was awarded the Noble Peace Prize in 2010, the Chinese government vehemently criticized the choice and placed his wife, Liu Xia, under unlawful house arrest, house arrest that continues to today. The Chinese internet was censored for any mention of Liu and the state-controlled media was not allowed to report on his prize.

Liu Xiaobo and his wife Liu Xia in happier times.

And even though, according to his wife, Liu was diagnosed by prison doctors with hepatitis B as early as 2010, his hepatitis was allowed to fester into liver cancer. It appears that that Liu was only given proper medical treatment when it was too late – when the antiviral drugs that slows down hepatitis B from becoming liver cancer would no longer work, when embolization of the tumor would no longer be effective and when surgery could no longer be used to save a life. It was only when the cancer became truly incurable that the Chinese government permitted Liu Xiaobo to go to a hospital – under constant guard – and die with his wife by his side. But even in his dying days, he was still denied dignity; the state-controlled media released pictures of Liu in the hospital, maintaining that the state had only given him the best care. They would not let him go abroad as he requested, likely fearing that he would use his final breaths to criticize the Chinese government.

The 2010 Nobel Peace Prize ceremony and the empty chair where Liu Xiaobo was to sit.

With his death on Thursday, the Chinese regime rushed to hold a funeral so that Liu’s friends and admirers could not make it. By Saturday morning, Liu Xiaobo’s wife buried his ashes at sea, likely at the demand of the Chinese government so that it could ensure that a tombstone would not be erected and potentially serve as a pilgrimage site. Liu’s brother was paraded on state-run TV stating that the quick sea burial was the family’s wishes. Even in his death, Liu was used as a propaganda tool, with pictures of his shell-shocked wife standing by the coffin and mechanically lowering his ashes into the ocean. Since Thursday, 1.4 billion Chinese people have experienced a news blackout on anything related to Liu Xiaobo. International news channels were pulled from the air, the state-run media has been ordered not to report on Liu’s passing and Chinese censors have been in overdrive, taking down posts with RIP and candle emojis as the Chinese people attempt to publicly show their respect to their countryman.

Thousands of mourners in Hong Kong hold a march in honor of Liu Xiaobo. (Photo courtesy of the Guardian)

China is the second largest economy in the world and most believe that it will soon supplant the United States as the Asia regional superpower. But yet this is how it responds to the death of one critique in its midst. A man whose only weapons were words and thoughts. If China still wonders why it can’t successfully project soft power internationally, this is it. While the Chinese government protests that it treated Liu with utmost care in prison, provided as much medical care as possible at the end, and permitted his family to hold a funeral, it still can’t ignore the fact that it imprisoned – and essentially killed – a man for his thoughts. The last Noble Peace Prize winner to die in state custody was Carl von Ossietky, the 1935 winner who, in 1938, died in a Nazi concentration camp. It’s never a good thing to be compared to the Nazi regime.

But even more troubling is that the Chinese regime’s suppression of Liu Xiaobo’s speech – both in life and in death – reflects a government that does not trust its own people. Is Liu’s words going to cause revolution in the streets? Probably not. But yet they cannot be heard. And in recent years, that distrust has only worsened. Two years ago, the Chinese government conducted a nationwide crackdown on China’s civil rights lawyers, lawyers who use the legal system to protect people’s legal rights; nothing particularly revolutionary about that tactic. And any civil society organization that becomes too successful, is shut down. The Chinese people are left with no outlet to shape their own society and demand that their government live up to its ideals. Instead, the Chinese government distrusts anyone who it believes dissents. But as Liu Xiaobo noted in the speech that was read at his Noble Prize ceremony, that enemy mentality will be a setback to progress:

Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy. . . . Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth. To strangle freedom of speech is to trample on human rights, stifle humanity, and suppress truth.

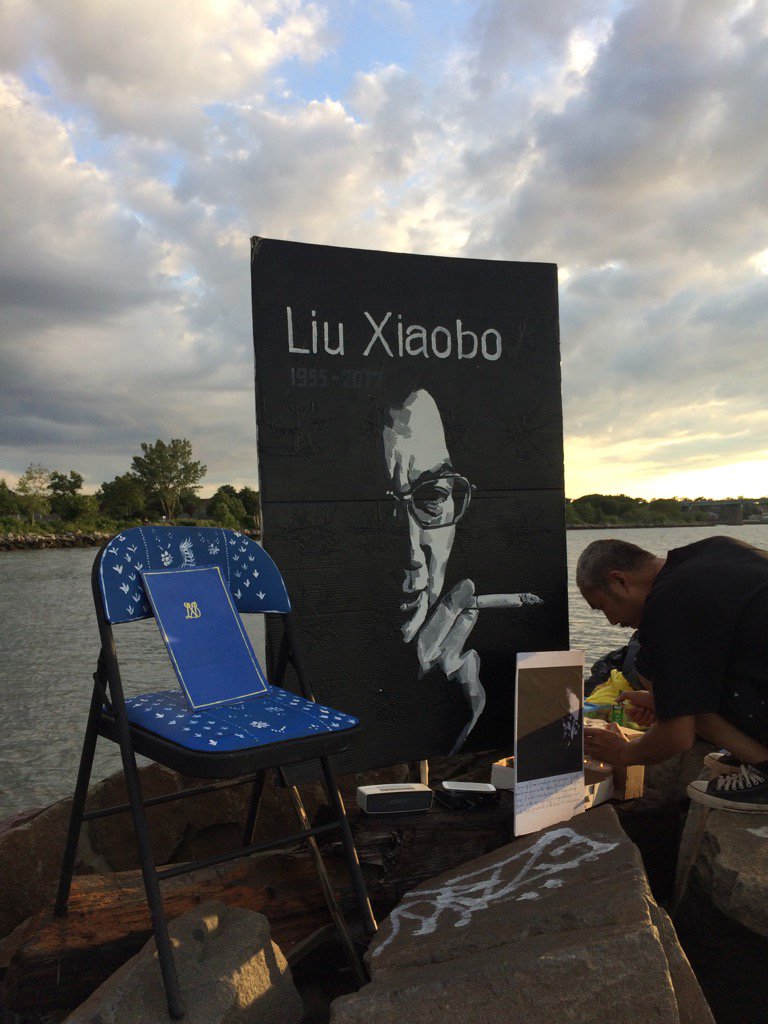

Impromptu memorial for Liu Xiaobo in Flushing, Queens, NYC (Courtesy of Facebook)

And Liu’s words and thoughts are not just ripe for the Chinese government right now but for all of us. Especially as the current United States Administration focuses less on human rights. On Thursday, President Trump issued a pathetic statement on Liu’s death through his press secretary. And only after he gushed about the greatness of China’s president Xi Jinping a mere hours after Liu’s passing. It wasn’t just China who lost a hero on Thursday, but the world. And the world needs the ideals of Liu Xiaobo now more than ever. May you rest in peace Liu Xiaobo and may we find the courage to continue your struggle both in China and in the world at large.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

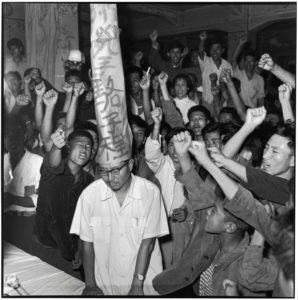

But every year, there are still those in China willing to risk their freedom to commemorate the violent crackdown on Tiananmen Square. A few years ago it was Chinese netizens reposting the image of the Tank Man – the Chinese citizen stopping a line of tanks, a banned picture on the Chinese internet – standing in front of a line of large,

But every year, there are still those in China willing to risk their freedom to commemorate the violent crackdown on Tiananmen Square. A few years ago it was Chinese netizens reposting the image of the Tank Man – the Chinese citizen stopping a line of tanks, a banned picture on the Chinese internet – standing in front of a line of large,

But Lim not only tells the stories of those who witnessed the crackdown, but also those for whom June 4, 1989 has no significance, namely the babies born after 1990. In one study that Lim conducted, only 15 out of 100 Chinese college students were able to identify the infamous Tank Man photo, a photo that epitomizes the Tian’anmen crackdown and that is perhaps one of the world’s greatest symbols of courage. She follows a college student who goes to Hong Kong to try to understand Tian’anmen, but when he returns to China, he just seems confused and deflated. And then there is the Patriot, a Chinese car salesman who goes to Beijing to participate in the government-sponsored protests against the Japanese. Their failure and inability to know about the Tian’anmen crackdown demonstrates the true effectiveness of the CCP’s re-writing of the Chinese people’s history.

But Lim not only tells the stories of those who witnessed the crackdown, but also those for whom June 4, 1989 has no significance, namely the babies born after 1990. In one study that Lim conducted, only 15 out of 100 Chinese college students were able to identify the infamous Tank Man photo, a photo that epitomizes the Tian’anmen crackdown and that is perhaps one of the world’s greatest symbols of courage. She follows a college student who goes to Hong Kong to try to understand Tian’anmen, but when he returns to China, he just seems confused and deflated. And then there is the Patriot, a Chinese car salesman who goes to Beijing to participate in the government-sponsored protests against the Japanese. Their failure and inability to know about the Tian’anmen crackdown demonstrates the true effectiveness of the CCP’s re-writing of the Chinese people’s history.