On Monday, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress began its review of China’s new, draft Mental Health Law. The draft – originally issued on June 10, 2011 and opened for public comment – has received much criticism both at home and abroad, in particular, Article 27 of the draft which permits involuntary commitment where an individual exhibits behavior that “disturbs public order” (扰乱公共秩序).

Prof. Michael Perlin

The Chinese government appears intent on ratifying the new Mental Health Law by year’s end, but the question remains, how will the new law change the current landscape?

Below, Prof. Michael Perlin, professor at New York Law School, Director of the Mental Disability Law Project, and author of the recently published “International Human Rights and Mental Disability Law: When the Silenced are Heard,” analyzes China’s new draft Mental Health Law, paying particular attention to its interplay with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), a treaty China has ratified.

Click here to listen to the interview with Prof. Michael Perlin or read below for the entire transcript.

Length: 31 minutes (audio will open in another browser)

**********************************************************************

[01:31] EL: Thank you Prof. Perlin for joining us.

[01:33] MP: Happy to be here.

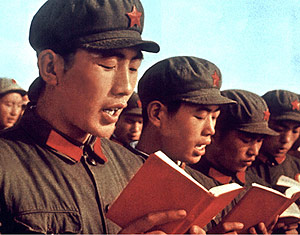

[01:34] EL: Let’s begin by talking about your new book, specifically Chapter Four which discusses the use of mental disability law to suppress political dissent. How long has China been using involuntary commitment to suppress dissent?

[01:47] MP: We knew that it has been going on back at least 40 years, it may be before that, we don’t know. This was written about first and most extensively by Robin Munro who brought most of this to the public attention and he gave some very, very serious examples of the misuse of state-sanctioned psychiatry in support of commitment of people who by any sort of standard, normative reason would not have needed commitment.

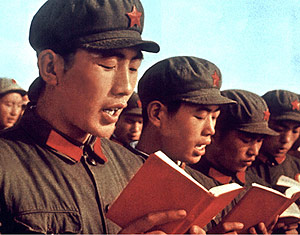

The use of involuntary commitment to squash dissent is not new in China and can be traced back to Cultural Revolution days.

[02:17] Sometimes it was done for political reasons, sometimes it was done for financial reasons. There is this whole other set of cases where people wanted to get rid of a relative because they wanted to take over a business or something. That was not unfamiliar to those who knew about this in the United States about the same time. But clearly it was being used to suppress political dissent.

[02:40] When I wrote Chapter Four of this new book, a lot of it flows from an article I’d done about four or five years before in the Israeli Law Review. When I did that research, it was kind of interesting to me. Most people know, or people who are interested in this whole general area, know that the former the Soviet Union, this was very common. And there were exposes, the World Psychiatric Association sends a delegation in the late 80s, early 90s, there were quite a few books written about it and articles. But China at that point nobody seemed to pay that much attention to, and it was pretty clear that the same kind of things were going on in China as were going on in the Soviet Union. Fast forward, the Iron Curtain fell, some of the abuses – not all – in the former Soviet Union had been remediated to some extent. But again what was happening in China was pretty much under the radar.

[03:40] It became known, interestingly, with regard to what is seen as the persecution of the Falun Gong. Is it a political group? Is it a kind of exercise? Is it meta-physical? I can’t answer that but it seemed very, very clear to me and to most neutral observers that practitioners and adherents were being singled out, and they were being marginalized as mentally ill. One of the things, we’ll talk about it latter, is why do governments do this and I will discuss that in a few minutes but it seemed to me that China in many ways was paralleling[the experiences in the Soviet Union]

[04:25] What is interesting to me is that in this new draft act [China’s draft Mental Health Law], of which I am enormously ambivalent I should tell you, I think…and I have sent some comments to other people about it….I think there are some other things that are better than China has had before but an awful lot of it strikes me as very problematical. [Much of it] would not only not meet constitutional standards in a Western country but also I think pretty clearly does not comport with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which China has ratified.

[04:58] It seems to me that [in] this new law, Article 27 — about the disturbance of public order — should be a red flag. What does that mean? We are sitting here on the corner of West Broadway and Leonard Street and how far are we from Wall Street where there is an occupation going on that seems to be spreading. Is this disturbing the public order? One could read the pages on Facebook and an awful lot of American citizens think it is. Is something like this was being done in Beijing or Shanghai would, could everybody be dragged away to a psychiatric hospital? Under the strict language of the Act, yeah, it probably could.

[05:36] EL: Well, in terms of that, and you sort of mentioned it in your answer. The Chinese government itself has the power under even the criminal law, arguably; I mean maybe it is not directly stated in the criminal law but they use the power to detain people indefinitely. Why do they choose to, for example Falun Gong and other dissidents, why do they choose to use a mental health analysis instead of using the criminal law when they are basically an authoritarian state. Why did the Soviet Union do that, why does China continue to do that?

[06:13] MP: It seems to me that there are at least three main reasons for that Elizabeth, and that truly is a great question. First of all, there are always some, albeit minimal, procedural safeguards in the criminal process. They

The criminal process in China has its limits

are not always adhered to. … I spent some time working in China with criminal defense lawyers and I was teaching them how to, pedagogically, how to do certain things but I also spent much more time learning and I realized that it is not a lot those of us who have practiced criminal defense work in New York or New Jersey would go “oh my God” [to much of what goes on in the criminal trial process in China] but at least there is a something there. There is nothing there on the psychiatric commitment side. So that’s number one.

[06:56] Number two, when there is a hearing, when there is an adjudication, there is usually a limit to the sentence. It may be a draconian sentence, it may be for many more years than we would think make sense. But at least there is a number there. Psychiatric commitment is, in these jurisdictions indefinite. And I should say, after the CRPD [the Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities], the Convention is ratified, I don’t think indefinite commitment without clear judicial review passes muster under the international human rights law.

[07:31] But the third I think is the most important. Because I think [psychiatric commitment] stigmatizes. We know that if we call somebody a mental patient, he will be discredited. And if he has political motives, that will mean, well, we can ignore them. I use this example, I think, in that book, about someone in Romania (when Romania was a completely authoritarian state) who was picked up, and his psychiatric charge was [that] he was carrying a sign saying that the prime minister of the country must go; the [rationale was], “Well if he thought he was serious that someone would listen to him, he must be crazy.” It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s a loop. But I think those three reasons together are really it.

[08:14] EL: Right now, before…..I know they [China] have the draft [mental health] law published right now and it was opened for comments back in the summer, but before that. Right now how does involuntary commitment work [in China]? Are there laws in place? Who makes the decision if an individual should be involuntarily committed? How does it work?

[08:33] MP: The decisions is made basically by the State. Someone gets picked up; very, very often family will call and ask: take my relative and send him to the hospital. And there is no independent assessment. In 1985….I should say to your listeners, I have been a professor since the mid-1980s but I was a real lawyer before that. I practiced 13 years both as a criminal defense lawyer and as an advocate for persons with mental disabilities. I filed an amicus brief in the U.S. Supreme Court in 1985 in a case called Ake v. Oklahoma in which the Supreme Court ruled that a person who is indigent had a right to a psychiatric evaluation at state expense if he was putting forth the insanity defense. The idea being that this is something that can’t simply be done, can’t be decided on the say-so of the state doctor.

[09:32] In China it is always done on the say-so of the State doctor. There is virtually no sense of independence. There is also no lawyer appointed. One of the issues that I think is really important; we know this, we know that both among the United States and in other nations, serious mental health reform only happens when there are lawyers assigned to represent patients. I know that sounds very lawyer-centric. Pardon me, I plead guilty to that. But if you were to go to the United States and go state-by-state and see where has there been reform, where has there not, it’s an easy question. Where have there been lawyers like in New York, the Mental Hygiene Legal Service, like in New Jersey, the Division of Mental Health Advocacy law office, like in DC, the Public Defenders Service/ Mental Health Division, that’s where it happens. In other nations, where you have it: Israel is a nation that has a robust public defenders office doing these things and they are enormously successful. Where there are no lawyers, reform doesn’t happen.

[10:29] There are no lawyers doing these cases on the ground in China. I believe that after ratification of the CRPD, this needs to happen. Commitment must be subject to the judicial process at every step. That is demanded by the CRPD and it’s not in the draft [Mental Health Law] much less in the older law.

[10:49] EL: So to clarify, the draft mental health law that has been proposed has no provisions for a lawyer to be appointed.

[10:57] MP: Correct.

[10:58] EL: And there is no independent review of a state’s decision.

[11:00] MP: One can ask for a review but it is absolutely, utterly optional. There is no sense that it is obligatory, it is not mandatory.

[11:09] EL: Now, in terms of involuntary commitment, you say that the decision is made by the state. Would that be – what division of the state? Is that the Ministry of Public Security or is it not clear?

[11:21] MP: It’s not clear. You have sort of two different ways it could happen. The Ministry of Public Security and

An Ankang Hospital in China

this whole Ankang hospitals that are really shrouded….I mean, I heard about them….oh my goodness…I’d been doing mental disability work my whole career. I’ve been doing international human rights mental disability work for 11 years. I’ve been going to Asia for nine years. But it wasn’t until about four or five years ago that I even heard about these hospitals. And they operate…there is virtually no way to find out what’s going on in them and that ministry is Public Security. The others go through the Ministry of Health, I believe.

[12:00] EL: So the Ankang hospitals are within the Ministry of….?

[12:05] MP: Of Public Security. And those involve people who are seen as being criminally dangerous. It’s a very, very murky line between criminality and other kind of dangerous behavior. Very often, it’s what you choose to call it. But there is very little, there is no review, and there is very little outsider involvement. It’s like a world in and of itself.

[12:33] EL: And in terms of that line between criminality and involuntary commitment….One of the things that is being heavily criticized both by foreign scholars and even Chinese legal scholars is this continued use of “disturbing public order.” And that’s included in the new draft mental health law. My question is….just to get to the people who write this law. Is there any sincerity in the use of this term? Does the Chinese government believe that….I mean is there sincerity in the belief that perhaps the expression of a different opinion is evidence of mental illness? And how do they get doctors on board with that?

[13:13] MP: It’s very hard for me to tell what was in their minds. There is no record of this. And you can come

Occupy Wall Street - Political Protest or Endangering Public Saftey?

with multiple explanations Elizabeth. On one hand you can look at it just plain meaning. Endanger public safety means somebody is standing in the middle of a main street screaming at cars, right? That could cause an accident. And that you and I would agree might endanger public safety. And that’s one possibility.

[13:42] [This is another:] … In this study that was done by the Equity and Justice Initiative of Psychiatry and Society Watch that was published recently which analyzes this commitment system in China, it is replete with example of people who were picked up and psychiatrically hospitalized because basically they were seen as dissident. It’s an over-used word. I am very concerned in any jurisdiction but especially, especially, in a jurisdiction that has this kind of track record of locking people up for disagreeing politically. I am very concerned that this kind of language, like in Article 27, is far too overbroad and I see that as a really troubling issue.

[14:29] Why do state psychiatrists go along with it? This is something I have been trying to deal with for 20 years in terms of thinking about it and you don’t know. I remember reading one study in which the researchers said – well you know if we went along for the ride we would get more vacation days or get a nice home at the beach – something like that. Which sounds so depressingly banal, right, but it also in fact may be so.

[14:57] Some may also feel as if they[examining psychiatrists] are an arm of the state. I have heard, I have been in meetings, just so your listeners know, I have been mainland China five or six times and have done quite a bit of work there and I have been at meetings with psychiatrists and I’ve tried to listen to what people say. Very often….most recently I was in Beijing in June this summer, and I heard a psychiatrist say – “oh well, you know, I can kind of look at this guy in the eyes and I will know if he needs to be institutionalized.” That kind of behavior was repudiated when I started practicing law, I heard doctors say that. That’s been repudiated in the States for the last twenty or thirty years.

[15:42] Very, very much of what I heard on this last trip to Beijing – Yogi Bera said it is déjà vu all over again – very much of what I heard was very close to what I heard in the early 1970s when I started practicing law in New Jersey.

[15:55] EL: Well in that regards, and this is a little maybe off topic because it’s not as much related to law, but has there been efforts….I know that there are a lot of rule of law projects from the US in China to help strengthen the legal profession. Have there been efforts to maybe create….strengthen the professional mindedness of the psychiatry profession in China? Has there been any attempts to do that and hopefully through that way, develop a grassroots feeling of independence? Or is that something that might just be too difficult?

[16:26] MP: If this was a TV show rather than podcast, your listeners would be seeing my face at this moment. Yeah, kind of, maybe, a little bit, not much. I know the World Medical Association has taken seriously some of these issues. There’s a psychiatrist in Mamaroneck, New York, Dr. Abraham Halpern, one of my heroes. Abe has been working on some of these issues for the last 30, 40 years. Mostly he is focusing on things like organ transplants now. But he has been a gadfly to the World Medical Association encouraging it, as has Dr. David Matos of Canada. But generally not so much. I don’t see this…..

[17:05] There is an interesting subtext issue here. One of the things I write about, and I discuss it extensively in this book, is what I call “sanism.” Sanism is the kind of irrational prejudice like racism, like sexism, like homophobia, in which we stereotype people with mental disabilities, we trivialize them, we typify them, we don’t take them very seriously. We treat them as less than people. Because of that, we generally – we meaning society – pay much less attention towards what psychiatrists do with purportedly “crazy people” than we do when there are other violations. When people mistreat women, when people mistreat children, when people mistreat gays, there is a predictable and appropriate outrage on page one on all the blogs. It doesn’t happen here.

[17:55] Internationally there is only one organization, a group called the Mental Disability Advocacy Center located mostly in Budapest, a couple of other sites in Europe, that is doing this work on a global level. I am working with my friend and colleague Yoshi Ikehara who is head of the Tokyo Advocacy Law Office (as I said before we went on the air) to create a Disability Rights Tribunal for Asia and the Pacific. But there is very little else that is being done.

[18:19] This is a population that people, even people who see themselves as traditional liberals – traditionally progressive, traditionally focusing on social justice – which just as well go away. They think it is yucky.

[18:34] EL: In terms of….focusing on the international efforts, you had mentioned the CRPD, what international law is out there that would push China forward in this regards? Since China has ratified some of the treaties, what can be done on an international level besides just issuing reports that they are in violation of the treaty?

[19:01] MP: That’s the hardest question Elizabeth; it’s the most important question. This treaty which has been on the books for three years….

[19:10] EL: And this is the CRPD?

[19:12] MP: Yes.

[19:12] EL: Which stands for?

China has signed & ratified the CRPD but does it follow it?

[19:13] MP: Which stands for the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, is without any question the broadest document ever written on behalf of this population. Importantly it repudiates the medical model and substitutes a social model of disability. In other words, this is not simply “we have sick people”; this is, “society deals with this population a certain way, [and we need to] figure out what to do.”

[19:35] Irony, off to the side, what is so interesting to me is how the role of psychologists is so limited in this draft act [China’s draft Mental Health Law]. The CRPD moves away from the medical model, [and,] as such, psychologists – non-physicians – the use of them, the reliance on them should increase, not decrease. One of the things that I am seeing between the lines with my magic decoder ring on is that there are struggles between the psychiatric trade associations and the psychological trade associations in China; the psychiatrists have much more political clout, much more legislative clout, so this is basically guild stuff. That’s there.

[20:14] So, going back to what you said before. It’s clear to me and I write about that extensively in the book, there are many articles that talk about due process basically, that talk about freedom from torture, freedom from cruel and unusual punishment, ant-discrimination, access to justice, on and on – and again I would be happy to send you some more recent things that I have written about it since I’ve written the book – and it seems to me that China is failing at all those.

[20:45] But then comes the question, and so what? What are you going to do? What can you do? One of the reasons why Yoshi and I are devoting so much time to the creation of what we call DRTAP, the Disability Rights Tribunal for Asia and the Pacific, is because in Africa there is a commission on human rights; in Europe there is a court on human rights; in Latin America there is a court on human rights, in each case, a court or a commission. There is nothing in Asia. There have been seminars, there have been meetings, there is this group called the ASEAN , to which seven nations belong; some [groupings of nations] belong to other [pan-Asian groups that deal with other issues], but there is no Asian-wide tribunal. Why? Good question. People talk about “Asian values,’ [but] I reject that [as the reason why there is no human rights body in Asia] and I could talk about that later if you want me to.

[21:31] But without that, a person can, ostensibly, theoretically, appeal any kind of a decision directly to the Human Rights Council of the United Nations. That’s pretty difficult for anybody to do. It’s difficult for a person in a nation with a developed economy, what we call the first world, it is certainly, virtually impossible for someone in China to do without a lawyer, especially somebody is not in Beijing or Shanghai or one of the major cities.

[22:03] I went to Xi’an a couple of times to do some work and I talked to a lawyer who said: “Prof. Perlin, I’m not sure if you understand. In our province, we get to court by horseback”. This was in about 2007, 2008; this is not 20 years ago. There basically, they have at this point in time, almost no legal recourse. What you can do is [appeal to] the court of public opinion. We’re trying to do that. But again I am very saddened and disappointed that this issue has not sort of spread beyond the small circle of people who take this seriously, who care about it, who write about it, who foment about it. I think some of the reason for that Elizabeth is sanism, that these people are just simply seen as not human, not as important.

[22:45] EL: So are you saying that this issue hasn’t spread beyond the small group that focuses on it, so a lot of maybe the US’ projects in China, do they….are there US rule of law project that are pushing this? Is it also I guess in some way our fault?

[23:01] MP: Yeah it is. Oh clearly it is our fault. … I am on the Chinalaw LISTSERV, as you are, and if you spend a month there you will see there are certain topics that get written about a lot. Some very serious topics. Certainly there are serious human rights issue dissidents, things of that sort, but most of it goes to business law. And that that does not go to business law, a lot go to things that are extremely important like environmental law. Anyone like you or I who have spent time in China know how serious these problems are. But there is virtually no attention paid [to the issues we are discussing here]. You and I could sit down after this is over and count on one hand the people who have done substantive posts in the last three years about this issue on that LISTSERV, and we would have a couple of digits left over. So yeah, I think that I can fault those generally interested in the “rule of law” or “just society” for not taking this seriously enough. Well you know everyone has their priorities, we can’t do everything and that’s true. But this is an area that virtually no one is taking seriously.

[24:05] EL: Back to China, in terms of the new draft mental health law, you said that you are extremely ambivalent about it. Could you talk more about your feelings about what is good, what’s not good.

[24:18] MP: The fact that there is a law; the fact that it sort of talks about the fact that there has to be some kind of structure to this; and the fact that at least there will be something to assess, something to test.

[24:30] But let me laundry list some things that I think are problematic. First of all, I don’t think whomever drafted it ever looked at the CRPD. It does not appear to me that that was ever done, and that should have been. Elizabeth, when I talk to people — I am very fortunate, I have gone and done human rights law on every continent (except for Antarctica, the penguins still haven’t asked for me) — I’ll say to people now, when you re-write your law – I was in Argentina two or three weeks ago and I spoke to the World Psychiatric Association and I spoke to people from several nations and I said exactly the same thing – if you are rewriting your law, on the left side of your desk, you need the CRPD and for every section you write, go and look at the cognate section [of your local law] and ask, “Are we in line with this or not?”.

[25:16] EL: Well let me just interrupt for a second about that, I know there has been a lot of talk about the criminal procedure law, who has assisted in drafting that, do you have any idea which agencies of the government have assisted in drafting the Mental Health Law, if there has been any famous academics…is there any transparency about that?

[25:36] MP: I don’t know. It may have happened, but I simply don’t know or it is something that I am just not a part of those conversations.

[25:45] As I said before, again call me lawyer-centric, I think there needs to be appointment of counsel…period. Article 29 through 32 talk about maybe commissioning a forensic mental disability evaluation agency for second opinions in some cases. But without a counsel, I don’t think it’s really going to make very much difference. I think any part, every aspect of commitment has to be subject to the judicial process every step of the way.

[26:16] There are lots of other things that I sort of saw going through it. On Monday, in my class on survey of mental disability law, we talked about the topic of sexual autonomy, the rights of persons to have some kind of sexual freedom, and I have written about this in an article I wrote in the Washington Law Review a few years ago about sexuality issues in Asia and in China, you might find that of some interest. Nothing about it there.

[26:43] Their criteria for commitment are not really clear. There has to be a causal relationship between mental illness and risk and dangerousness. That is never spelled out.

[26:52] There is nothing about the institutionalized patient’s right to refuse medication, a huge, huge issue.

[27:03] There is a whole thing in Article 24 about when relatives can send a “suspected mentally disabled person” to the hospital. Without criteria that is really, really problematic and I think that is an issue that needs to be dealt with. Very, very often, somebody will come to a psychiatrist and say “doctor, my brother, sister, whatever is crazy” and that becomes sort of the fact in evidence, even though there’s no [actual] evidence before [the psychiatrist.”]. That’s where we start out and I think that’s really a serious, serious issue.

[27:34] As I said before the “endanger public safety language” in Articles 26 and 27 is especially problematic, especially, Elizabeth, given China’s history. Article 28 talks about “diagnosis” but “diagnosis” is not “risk assessment”. A person can have what we would call in the States an Axis 1 diagnosis – schizophrenia, bi-polar depression, major depression – and that does not mean they are committable because [to be committable], you have to have with that, as a result of that, the likelihood of serious danger to self or others. That is not spelled out at all.

[28:14] The possibility, everybody has ballyhooed in Article 29 about this sort of duplicative examination…I am not convinced at all that it is going to be really independent.

[28:27] Starting in Article 30 it talks about forensics but I am really puzzled because there is nothing else in here about the criminal process. It is just not clear to me what that is.

[28:38] I think rights need to be enumerated. If you go to Article 34 we also have to articulate the fact, and again this is constant both with the CRPD and all developments of the last forty-plus years that the right to treatment has to be in the least restrictive alternative. We have to talk about community treatment. We have to talk about de-institutionalization. We have to talk about congregate care, halfway house, on and on. That’s not here anywhere.

[29:03] Psycho-surgery is discussed in Article 39. Absolutely not. That should never be an acceptable treatment.

[29:09] I was puzzled again as I said to you by the lack of….how psychologists appear to me to be squeezed out. Again, I see this as kind of guild-mentality; it troubles me a lot.

[29:25] What can be done about this, I’m not that smart. I have sent my comments in to other people who hopefully have the ear of those who do listen. Hopefully something will happen. But I looked in file before you got here but I have not heard back, gotten anything substantive on this in the last two months.

[29:41] EL: Well that’s what I want to ask you in a close out question basically. There has been actually some verbal criticism by Chinese scholars about the draft mental health law and highlighting a lot of the things you have mentioned including the endangering public safety, disturbing public order issue. Do you think the Chinese government will listen to any of this criticism? Do you anticipate that the draft will change before it is adopted? Or are these things that the Chinese government hasn’t been able to get past yet?

[30:15] MP: I wish I knew, Elizabeth. I say jokingly I’m smart, I’m not that smart. There will be some changes. I think if they made no changes at all that would be a public relations disaster because that would mean we are ignoring everybody, we are doing just what we want, and take a hike. There will be some changes. I’ll say some of it will be better. How much of it? Ten percent? A quarter? I don’t know. I wish I could be more optimistic and say – oh they are going to listen to everything we say – no, get real, they’re not. But I am hopefully that it will be incrementally better and the way that it is written will give us more and people who are on the ground more to work with.

[30:59] I’m very sensitive to the fact, I go to China once a year, at the very most twice a year, I live in New Jersey, I work in New York, I am a foreigner, I am an outsider and all I can do is listen and learn and share some ideas. It has to be done by the people on the ground. I certainly spend a good deal of time talking to them and I hope that as a result of that something happens. I remain….I’ve been doing this work for a long, long time…I remain an unflaggingly optimistic guy so I hope it is going to happen.

[31:30] EL: Okay, well, I guess we will find out. It is suppose to be passed by year end. Thank you very much Prof. Perlin for your time and your knowledge.

[31:40] MP: Thank you, Elizabeth, it was a pleasure.

Jurisdiction is central in any legal system; it is jurisdiction that gives a court its power to administer justice. Without proper jurisdiction, a court’s opinion is defective. Thus, given its importance, all legal systems design specific rules governing when a court has jurisdiction over a case.

Jurisdiction is central in any legal system; it is jurisdiction that gives a court its power to administer justice. Without proper jurisdiction, a court’s opinion is defective. Thus, given its importance, all legal systems design specific rules governing when a court has jurisdiction over a case. assign a People’s Court at a lower level to try a case over which jurisdiction is unclear and may also instruct a People’s Court at a lower level to transfer the case to another People’s Court for trial.”

assign a People’s Court at a lower level to try a case over which jurisdiction is unclear and may also instruct a People’s Court at a lower level to transfer the case to another People’s Court for trial.” On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email