The Anatomy of a Crackdown: China’s Assault on its Human Rights Lawyers

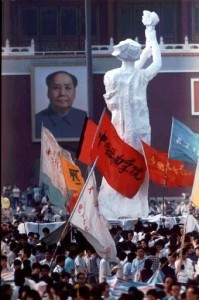

When the Chinese government detained, harassed and disappeared over 280 human rights lawyers and legal activists in July 2015, the international community took notice. These simultaneous, country-wide, nighttime and early morning raids made front page news in the United States, often described as the Chinese government’s attempts to eradicate cause lawyering from its shores.

When the Chinese government detained, harassed and disappeared over 280 human rights lawyers and legal activists in July 2015, the international community took notice. These simultaneous, country-wide, nighttime and early morning raids made front page news in the United States, often described as the Chinese government’s attempts to eradicate cause lawyering from its shores.

But as the Leitner Center and the Committee To Support Chinese Lawyers‘ new and seminal report Plight and Prospects: The Landscape for Cause Lawyers in China reveals, in some ways, these arrests and detentions are the least of the human rights lawyers’ worries. Instead, Plight and Prospects makes clear that over the past five years, the Chinese government has quietly and methodically used a more effective means to limit the space for cause lawyers: the law.

Although the Chinese government still relies on extra-judicial measures such a illegal detentions, torture, constant surveillance when “free,” and pressures on families, employers and even landlords in an attempt to destroy the lawyer’s life, Plight and Prospects underscores that soon these extra-judicial methods will be unnecessary. Through amendments to the Lawyers Law (amended 2007), the Criminal Law (amended 2015), the Criminal Procedure Law (amended 2012), the National Security Law (passed 2015) and through the annual lawyer licensing procedure, the Chinese government can limit the ability of cause lawyers to practice and still pay lip service to “the rule of law.”

As Plight and Prospects points out, under President Xi Jinping (pronounced See Gin-ping) there has been a stepped-up effort to enshrine in law methods that will effectively break the cause lawyering movement. But even before Xi took power in 2012, there were already concrete efforts in the Chinese government to use the law to limit human rights lawyers’ advocacy.

Take for example, the Lawyers Law. Amended in 2007 and believed to provide the profession with greater protection to practice law, it has proven to be a double-edged sword. Sure Articles 36 and 37 of the Lawyers Law maintain that the lawyers “rights to debate or a defense shall be protected in accordance with the law,” but Article 49, which lists the examples of lawyers’ conduct subject to punishment, increased the number of categories from four to nine with the 2007 amendments. Added to the Lawyers Law as Article 49(6) was instances where a lawyers “disrupts the order of a court . . . or interferes with the normal conduct of litigation or arbitration.” Vague and unclear, this provision could be used to limit the courtroom advocacy of lawyers who take cases the government just does not like.

And in 2010, it was. In April 2010, Tang Jitian (pronounced Tang Gee-tee’an) and Liu Wei (pronounced Leo Way), two cause lawyers who had represented a practitioner of the spiritual movement Falun Gong and who both quietly left the courtroom in protest when they were unable to present their client’s defense, were hauled before the Beijing Bureau of Justice for a hearing concerning whether they should be disbarred (see China’s Rule of Law Mirage: The Regression of the Legal Profession Since the Adoption of the 2007 Lawyers Law). While Tang and Liu both raised Article 37 – that their ability to practice law was being infringed upon – as a defense, both were permanently disbarred under Article 49(6) for “disrupting the courtroom.” (Id.).

Further attempts to limit the advocacy of human rights attorneys have been proposed more recently by the All China’s Lawyers Association (ACLA), the national bar association that operates under the guidance of the Ministry of Justice. ACLA’s draft revisions to the Lawyers Code of Conduct (proposed in 2014), if adopted, could limit methods of advocacy that lawyers must use when representing vulnerable populations, including the use of the media and internet (draft Article 9), organizing demonstrations or “inflaming” public opinion (draft Article 11), or supporting organizations that do cause lawyering (draft Article 13). These draft provisions are in contravention of Article 35 of the Chinese Constitution which provides for freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration.

The Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) provides another example. Amended in 2012, it was hoped that the amendments would better protect suspects’ rights and ensure a more fair system. But, as Yaqiu Wang at China Change has pointed out, it left one gaping loophole: “residential surveillance at a designated place.” Articles 72 through 77 of the CPL deal with residential surveillance. Although this sounds like a more mellow way to be detained than at a detention center, for those investigations that might involve crimes of “endangering state security,” “terrorism” or “serious crimes of bribery,” residential surveillance does not occur at one’s home. (CPL, Art. 73) Instead, it occurs at an undisclosed location – the family is informed of the fact that the person is being detained under residential surveillance (required by CPL, Art. 73), but not necessarily of the location of the residential surveillance. The suspect has a right to retain a lawyer (see CPL, Art. 73, applying CPL, Art. 33). But because “residential surveillance in a designated place” presupposes a possible state security, terrorist, or serious bribery charge, the requirement that a meeting with the lawyer take place within 48 hours (CPL, Art. 37) is suspended for those possible charges. (CPL, Art. 37). Instead, any meeting must be approved by the police. (CPL, Art. 37). Which fits with the rules that the suspect must follow when in residential surveillance: only with permission of the public security agency can the suspect meet or correspond with someone else. (CPL, Art.75(2)). And it is not hard to place someone under residential surveillance at a designated place. All that the police need is approval from the chief of public security above the county level. (see Ministry of Public Security Implementing Regulations of the CPL, Art. 106). Residential surveillance pending investigation is permitted for up to six months. (CPL, Art. 77).

As Plight and Prospects points out, the use of residential surveillance at a designated place has been used with abandon in the current crackdown. The section entitled “Whereabouts Unknown” highlights that eight of the suspects still being held as a result of the July crackdown are held under residential surveillance at a designated place but no one outside of the police, not even their lawyers, know where. Amnesty International researcher William Nee has pointed out that although a legally-authorized form of detention under the amended CPL, it still carries with it the dangers associated with enforced disappearances: held secretly and without access to a lawyer, these suspects in residential surveillance are vulnerable to torture to force a confession.

By being able to point to the law it is using to crackdown on cause lawyers, the Chinese government likely aspires to punt the international critique of a failure to follow a rule of law. It is following a rule of law, it will say. But as Plight and Prospects notes, it is a hollow one where the Chinese government undermines its own Constitution, other provisions of many of the laws it has used in the crackdown, its international treaty obligations as well as the desires of its own people.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email