Andréa Worden – The Cries of Changsha

Today, China Law & Policy concludes its interview series for the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre. Today, we are joined with Andréa Worden. Andréa is a noted China expert, human rights advocate and she will be teaching a course on human rights in China at John Hopkins University this fall. But back in the spring of 1989, she was an English teacher at Hunan Medical University in Changsha, China. And as a result, experienced firsthand the student protests that were happening in Changsha and then the subsequent crackdown.

Andréa has written about her experience, first, as a chapter in a book containing accounts of some of the pro-democracy protests outside of Beijing and then 15 years later, for China Rights Forum. Today, she’s going to talk to us about some of her experiences there.

Listen to the full audio of the interview here (total time 40 minutes):

Additionally, you can read the transcript below or Click Here To Open A PDF of the Transcript of the Interview with Andréa Worden

CL&P: So Andréa, just to start, what started the protests in Beijing, for the Beijing students it was the death of Hu Yaobang back in, I believe, April of 1989 and that kicked off a lot of the pro-democracy protests there. For your students in Changsha, what were their reactions to Hu’s death, or did something else cause them to start protesting?

AW: Well first, Elizabeth, it is great to be with you again in the run up to the anniversary of June 4, and I really appreciate your taking the time to talk with me about this incredibly important event. I wanted to mention that, just first off, something that is not particularly well known is the fact that in more than 340 cities in China during the spring of 1989, there were protests. Likely that number is much higher. That figure comes from the compiler of the Tiananmen Papers.

I recently saw a figure online, unfortunately without a cite, it was the Wiki on the Tiananmen protests that mentioned the number 400 [cities with protests in 1989]. But my own feeling is that it’s probably even more than that becau

The distance between Changsha and Beijing.

se some of my students in Changsha were from fairly small towns in Hunan. When they went home during this period of April and May of 1989, they said even in their very small hometowns, villages even, there were protests. So it was truly nationwide and unfortunately, we probably will never know the full scope of the pro-democracy protests in China.

So right, April 15 was the day that Hu Yaobang passed away. We know that was obviously a critical moment in Beijing, and that’s what launched the student protests in Beijing. Also, in Changsha, many people were very sad when they heard the news. Hu Yaobang actually is from Hunan, so there was this sense of “he’s our native son” who was viewed very much by many people as being sort of a hero and somebody that they really had hope for, as somebody who supported intellectuals, who supported the students, and was very much involved in the economic reforms and some political reform under Deng.

My particular school. . .so Hunan Medical University medical students, they have a reputation for not being particularly political. But there were a few universities on the other side of the river that goes right through Changsha that were known to be very active politically both earlier in 1979 and 1980, and there’s also an election movement during that time period at those colleges. Those colleges include Hunan University, South Central Industrial University, and Hunan Teachers College. Then it was also known as Hunan Normal University. Over on that side of the river, the other side of the river, there were mourning activities or events [for Hu Yaobang], but no major protest as far as I know, yet.

CL&P: When your students in Changsha at the Hunan Medical University, when they started seeing the students in Beijing protest at Tiananmen Square, what were their reactions to it? Did they talk to you about it? Did they feel like they could talk to you about it?

AW: A few of my students that I had become quite close to as good friends, they felt very comfortable I think speaking with me about it. They were excited. They were sort of amazed, and there was really this sense of hope that students could come together on such a massive scale and speak out about the things that they also very much felt. Those things ranged from inflation, which was really a huge problem then at that time. My students felt it personally when the prices at the cafeteria went up, like doubled, and some of them said, “My parents can’t afford this.”

CL&P: Right.

AW: So there was that on a very personal, practical level. But then also corruption was everywhere. That became a big theme of the movement both in Beijing and in Changsha. Corruption, inflation and then certainly freedom, democracy. Regardless of what they might have viewed democracy as being or how they might define it, my clear sense was a lot of this was about personal freedoms, more personal freedom, certainly freedom of speech, freedom of expression.

Protests in Changsha the Spring of 1989; taken by Andréa Worden

CL&P: So in Changsha itself, when did the protests really take off? You mentioned that they were two different areas of universities and you were in the area on the other side of the river with Hunan Medical University. When did your students start participating in the protests or most of the university students at Hunan Medical start participating?

AW: So the students on the other side of the river – the more politically-active side of town – they had organized demonstrations, we could say a smaller-ish demonstration or just a gathering, on April 15th. Just really, truly mourning this leader. And of course, in China mourning a leader that has passed invariably ends up commenting on the current leadership, even implicitly. So that was happening.

The other folks, the more active folks organized demonstrations for April 22nd, April 26th and May 4. I should say also I don’t have complete information. So there may well have been more than this. This is what I have noted and I’ve written in my article that you’ve mentioned.

So at this point still my students were definitely, I think, interested in watching. Some I’m sure went out to maybe peek and take a look, but the students, the Hunan Medical University students were not yet actively involved en masse.

CL&P: Did they ever become involved en masse?

AW: Yes, they did. Yes. Let me tell you a little bit about that. It was this sort of. . . they were watching things very, very carefully. They were able to get information from the VOA and the BBC over. . .

CL&P: Yeah, a shortwave radio.

AW: Yeah, exactly. So Voice of America and the BBC from England, they were able to get that over a shortwave radio. And so what would happen – of course not everybody had a shortwave radio – but the people who did would write out on large poster board or pieces of paper, they would write out news from Beijing. They’d plaster these large pieces of paper of all over the city or actually in main areas, certainly at all universities and at big intersections people were watching, were looking around.

Also, there were certainly, there were hints on the evening news. A dialogue with the students in Beijing was coming up. This was also of course televised. [Ed. Note: During the course of the pro-democracy protests in Beijing, the central government held three dialogues with the Tiananmen student leaders – April 29, May 14 and May 18. All three were televised; some live, some on tape-delay]

So there was that and there were also of course at this point too, it’s something called chuanlian [串联], which is the students networking or people networking across cities, across boundaries, across the country to try to mobilize other students as well as workers. This was a term I think that came from the Cultural Revolution. Some of the Changsha student leaders were going up to Beijing and they were bringing back information.

So basically what happened at my school – again, probably one of the last schools to get very involved – was one [dorm] room of male students from my class, they decided to fast, to hunger strike or fast [after] one of the days the students had started their hunger strike in Beijing on May 13, and this really moved people. [Ed. Note: Andréa clarified this timeline in a follow up conversation with CL&P. She recalled this group of her students going on their hunger strike a few days after Beijing students did, on May 17, 1989.]

So they [the small group of Hunan Medical male students] were inspired and moved by the students who were hunger striking in Beijing and they said, “We had to do something. We couldn’t just sit here and go to class and not do anything, right?”

A photo from Andréa taken on May 17, 1989 in Changsha showing some of the hunger strikers in front of the provincial government headquarters

So anyways, on May 17, one group of this one room of these young [male] students put a sign up on their door and they said that they would just fast for one day and they weren’t encouraging anybody else to do anything. This was just something these however many boys, I can’t remember, six, eight, had decided they were going to do as a group. So that also inspired so many people at Hunan Medical University. So when some of the girls in our class found out what the boys were doing, they thought “oh, we can’t [not do anything]. We have to support this too.”

So anyway, it kind of went room by room, or dorm room by dorm room. The girls got involved and the students from other classes heard what was happening. Word travels fast. Basically very soon there was a lot of hubbub and momentum, people were fasting for the day, wanting to show support for the students in Beijing.

I wanted to share this story in part because it shows how important one person – or here seven people – deciding to do one thing, this personal act of protest, how that can just totally truly spark a much larger movement or event or action because it has a sort of amazing ripple effect of just inspiring other people to take action.

So that evening the students, the student union leaders, got onto the loud speaker, and announced on the loud speaker that the Hunan Medical University was going to participate in the city-wide demonstration that was going to be held that night. I don’t think that was just a coincidence. It might have been, but. . . .

CL&P: Right. So at Hunan Medical University, once this started around May 17th, the hunger strikes and then the student union leaders announcing that the university was going to participate, what happened with classes? Did they kind of just stop or did students try to balance classes or was it. . . .

AW: So that’s a really good question and they were like on and off. My recollection of this whole period was not a whole lot was happening in terms of classes. I think there was some coursework happening. I recall my students were feeling very stressed about missing classes. They were very obviously concerned about their grades, but they certainly also wanted to participate so there yeah, some classes were being held on certain days but there were other times when basically it was like every day seemed to be a demonstration; there were class boycotts, there were hunger strikes, there were sit-ins. Also, there started to become worker strikes as well. And some students just went home.

CL&P: In the reaction of the female students, I know in your essay “Despair and Hope: A Changsha Chronicle,” you actually do discuss about how the 1989 protests and the movement that was catching the nation was actually in some ways empowering to female students who engaged in the protests. Can you talk maybe a little bit more about that? And put it in a little bit more of a context?

Changsha shopowners providing free tea to the students to show their support – a photo by Andréa Worden from May, 1989

AW: Changsha came alive during this period of time, so roughly let’s say early May or mid-May through June 4, and it was incredible to witness that. There had been such a feeling of hopelessness beforehand and also this feeling of just total boredom and depression that people felt like they had no [choices]. One student had said, “Oh, I thought I was going to go to college and leaving my parents, and was excited about more freedom,” and he said, “When I got to Hunan Medical University it was like I was in prison.”

They had so many rules and were so tightly controlled and they had to sort of watch every step that they took and just be very, very careful. They just felt truly oppressed or repressed, suppressed. They couldn’t really express their individuality. There was a lot of conformity. You had to say the right the thing, you had to act a certain way, and I think students kind of particularly enjoyed our English, not just mine but my fellow English teachers, our classes because we were sort of like, “Okay, you can come to English class and you can say whatever you want.”

We encouraged them obviously to say how they felt and write essays about kind of interesting topics. I think they also felt that they could say more in English than they could in their Chinese classes in terms of maybe possibly “sensitive issues.” They were still kind of watching because they had to still be careful, they were watching sort of what they were saying but it was a breath of fresh air, our classes. I think that they didn’t have much of that elsewhere. So that period when the demonstrations had started, when people were sort of writing these wall posters, when they are out and about looking at and watching the demonstrations or just talking among themselves, the students were talking among themselves, what’s happening? What’s happening in Beijing? Where is this going? Or analyzing what was happening on the political level. Clearly there was a split that was coming to the fore between Li Peng and the hardliners, and Zhao Ziyang. People were very busy talking about that, analyzing this, where was it going to go? What was happening? They were talking about also the dynamics among the schools in Changsha. So it was just this heady time. Basically everyone I think, many people felt they had now the space and the freedom to speak out, including women.

So that was fantastic to see both because they looked so alive, they looked so engaged and happy and sort of free, really free. Anyway, both the men and the women, so the female and the male students, but I think it was interesting because the male students would kind of be quite surprised and sometimes I was too when they would see one of their female classmates who had been perhaps quite maybe fairly demure, shy, didn’t seem to be thinking about much of anything, making speeches on the corner, on the street corner in Changsha about large ideas and large principles of freedom, transparency, accountability, democracy, what do we do about corruption. Just talking, talking, talking.

So in that respect I think everybody felt empowered and that was wonderful. It was inspiring to see and it was also, I think they all inspired each other and I think just people took a particular pleasure at seeing the female students step up into that role.

CL&P: Then so on May 20th, 1989, martial law was declared. What was the reaction in Changsha?

AW: I also should back up a little bit. April 26 [1989] was the day The People’s Daily issued this editorial that declared the Beijing protests, what was happening in Tiananmen Square, declared it to be “turmoil.” So dongluan [动乱]. These sort of naïve – they didn’t use the word naïve – but students were being taken advantage of by a small handful of people who were anti-party, who were anti-socialist.

Very hard line, they didn’t acknowledge the students’ patriotism, which was very much front and center in Beijing and also Changsha. People [protesting] were very, very clear that they loved their country; they loved China. They were unhappy about the political system. They were very unhappy about corruption and they were looking for change and more freedoms. So that editorial, just like in Beijing, caused a huge reaction [in Changsha]. Anyways, so more protests, then in terms of May 20, Changsha, the people in Changsha were reacting to what was happening in Beijing.

When martial law was declared – it was the night of May 19th but actually it was supposed to take effect May 20 – people were very upset, very despondent. They felt like okay, this is done. Again it was despair. Our country is going to mobilize the army against us, against the people, against the students and so it was horrible. They felt betrayed.

CL&P: So just. . . and when martial law was declared, how did you feel? Were you scared?

AW: So I sort of felt similarly to my students. I had noted in my article, there was this feeling of “how could our government be so cruel?” So it was this alternation between feeling hopeful and feeling disempowered and just feeling despair. I felt, I couldn’t believe it. I was also just felt absolutely. . . .I also felt depressed and just thinking “oh, this is not going to end well,” but I wasn’t actually scared in Changsha.

As it became clear pretty quickly that troops were not going to proceed into the sort of inner city of Beijing or to Tiananmen, they were sort of stuck on the outside of suburbs, and that there was so

Army troops in Beijing when martial law was declared. The students were able to push them back without incident

much popular support. That then, once the students in Beijing went back out on the streets after May 20th, or maybe that was even the night of May 20th. Anyway, they went back after this [martial law] was declared because they saw that the people were essentially on their side and so when that happened there was this other wave of . . . . [Ed. Note: When martial law was declared, the Chinese government had organized the Beijing division of the army to stop the protests. However the student, workers and citizen protesters stopped the troops from entering the city and, with no shots fired, pushed the troops back.]

CL&P: Wave of hope.

AW: . . . hope. It’s like okay, there is a possible hopeful outcome for all of this.

CL&P: Then did the students in Changsha continue to protest when they saw the Beijing students?

AW: They did, yes. They absolutely did. Right, so that news from Beijing, about essentially the people of the city stopping the advancement of the troops, definitely gave the people of Changsha and the students in Changsha sort of a renewed sense of hope, yes. They continued to protest in various ways.

CL&P: Then the night of June 3rd into the morning of June 4th is the massacre at Tiananmen Square. So the massacre [also] in and around Tiananmen Square that occurred the night of June 3rd into the morning of June 4th, how did you learn about it?

AW: So I learned about. . . I learned about it from my students actually. So they had gotten up earlier than me on Sunday morning. That was a Sunday morning, June 4. And a handful of them came running over to our, excuse me, to the Yale-China house where the teachers were and were yelling to us from outside and just to say what had happened and they again had heard from. . . not only I guess at this point VOA but also the government was starting to spin this.

Actually one other thing I wanted to say that was also actually incredibly hopeful there was a three week period in May where the newspapers, the journalists probably throughout China, were actually reporting the real news, which was incredible, including in Changsha. So the Changsha Evening News – it’s just something I would read – they were reporting what was happening in Beijing, actual real news because there was sort of this opening.

CL&P: Ostensibly the newspaper would still be government-controlled. . . .

AW: Right.

CL&P: . . . but they were still writing the truth.

AW: Right, because they were protesting. The journalists, journalists were protesting on Tiananmen Square. Yes. They’d gotten involved. And also Shanghai there were large journalist protests, so that’s a whole other piece of the story that’s fascinating.

But anyway, so the morning of June 4, people were just incredibly upset, everybody. Some people were showing it more vividly. They were manifesting their emotions in sort of a more visible way than others, but we were just. . . . I remember just personally being floored, amazed, sort of incredibly depressed and also really felt for my students; they were very upset about the news.

We also just kind of couldn’t believe it. It’s unbelievable, right? The People’s Liberation Army opening fire on unarmed protestors. Peaceful protesters. So that is a vivid memory of learning about that from my students that morning.

Then after that, so June 4 later in the day and June 5, probably even into June 6th there were – yes, definitely into June 6 – there were definitely, there were protests against the military suppression.

CL&P: In Changsha?

AW: In Changsha. They were protesting. Also again, this is another part of the untold story. There are many, many untold stories of the spring of sort of April 15 to June 6, 7, 1989 and this is one of them. There were many, many, many cities throughout China where residents, workers, students were protesting against the violence in Beijing.

Photo taken by Andréa on June 5, 1989 – sign in Changsha that says “People of Changsha take action/rise up to support Beijing!”

CL&P: So after the Tiananmen Massacre on June 4th, other cities, including Changsha continued to protest even though they knew full well that there was a possibility their army could open fire on them.

AW: Yes. Right, so we know Louisa Lim has done a very nice job in her book, The People’s Republic of Amnesia, telling what she could find out about the Chengdu story. Still, she’s like, “There’s much we don’t know.” But she does a great job laying out what she’s been able to discover. I think also from other things that I’ve read it’s clear that the mobilization at that time of the military – June 3, 4 – that that very likely was a call across the country to all major cities. Because basically in Changsha, people kept saying there’s a rumor that troops are right outside the city. [Ed. Note: In our interview with Frank Upham about his experience in Wuhan during this time period, he too recollects the “rumor” that there were troops outside of Wuhan, ready to suppress the post-June 4 protests.]

And they’re going to come in at any time. And if you read other accounts in the book that you mentioned, The Pro-Democracy Protest in China: Reports from the Provinces, I see many of the other reports from the provinces, same thing. People were hearing that the troops were right outside the city ready to sort of. . . ready to come into the city and suppress protests as necessary. So there was basically a nationwide mobilization.

So people were kind of scared about that. That’s one moment where I was definitely feeling a bit scared because there was clearly an anti-Western turn, particular anti-American turn at this point. Not among the students or friends or faculty, but just overall politically. The CCP, the party secretary at the school and in Changsha, it was like this is an American. . . .Americans are behind this. Fang Lizhi taking refuge in the [US] Embassy with his wife. So this was all unfortunate because we then, the American teachers, were very concerned that we were going to become targets.

What was interesting about that time was that these protests also, sort of in a way became a bit more radical in they basically were causing – it was workers, it was students, it was residents. Many people were involved in blocking the train tracks so no trains could move. So the whole railroad operation was at a standstill.

Also, blocking major intersections. So they would corral buses and trucks. It was really, it was anarchy but it was peaceful anarchy in a way. These were actions that the Changsha populace supported.

There was debris in the streets. I remember the ride out to the airport. [Ed. Note: Andréa left Changsha on June 11, 1989]. The driver was trying to figure out how to get around all these roadblocks. We just saw there was a lot of sort of debris in the streets. So anyway, yeah, I’m not sure if I answered your question, but yeah, so they went on for a couple days but there was also a sense of who’s really in control? Also, again this fascinating feeling of this is so incredibly unusual.

CL&P: So your experience in the spring of 1989 in Changsha, what impact did it have on you?

AW: It was an incredible moment, incredible time. It was very dramatic. So our exit [on June 11, 1989], our leaving, we left very abruptly. It was really sort of an evacuation. Yale-China Association essentially said, “There will be a plane and you are getting on it and you are coming back.” Our parents were of course like, “Get out of there.” As we were leaving, many people said, “we don’t know what’s going to happen and you have to tell the world what happened here in Changsha.” Because people knew that they wouldn’t then be able to write about it or talk about it or even develop their photographs.

I was thinking about this recently. When I was out watching the protests and sort of taking photographs and documenting, just noting down some of the wall posters, some of the slogans, everyone had a camera, or some people had cameras and were taking photos. Where are all those photos? After June 4 people could not get that film developed. So where did all that go? There’s all this sense of this missing history and I think also people realizing they were not going to be able to tell their story. [Ed. Note: On May 31, 2019, Jian Liu, a student protestor in Beijing in 1989, developed some of his rolls of film from that time.]

I think they were very proud that they came out to support Beijing, to support the students and the workers. So the Changsha workers also got very involved in all of this, which of course made everybody in the government, Party folks, the most nervous. They felt really proud because this was such an empowering moment for them and they were like “we did something here. We didn’t succeed in the end. We want the world to know. We want people to know.” So I did feel this sense of like wow, returning to the US, I had this new sense of feeling very appreciative of the freedoms we have here and the rights that we have here. And that the absence of these rights and freedoms were just so apparent immediately once it was clear that the hardliners [Li Peng, etc.] had won this battle. That people wouldn’t be able to talk about this, and that. . .again, they had to toe the party line. My students had told me that they had two weeks of mandatory political education in the fall of I think it was, yeah, fall or maybe the summer, later in the summer.

Some of them said it was horrible. Some of them totally bought the party line. So anyway, so I felt very much like I wanted to do something to help support the democracy movement in China because it wasn’t going away. These feelings were. . . and these desires, these wants, were felt widely in China and I wanted to do what I could with the freedoms that I have to support their efforts. So when I got back I was starting a PhD program in Chinese History at Stanford, but I was quite involved in Human Rights in China [HRiC], it was just starting to get going – the organization Human Rights In China – doing what I could to help. Also to try to tell the story I helped put the book together, Children of the Dragon, for Human Rights in China. So, I have been involved on and off in various ways over the years in this cause. It’s basically taken on different forms and shapes over the years.

CL&P: What do you think ultimately is the legacy of the Tiananmen Massacre?

AW: So probably there are a few different answers to that. I think it’s an important question. One aspect of the legacy, or one legacy. . .there is very much, what did the Chinese Communist Party learn from this? Deng Xiaoping early on said that this is all – it’s in the Tiananmen Papers and it’s in Zhao Ziyang’s “secret journal,” The Prisoner of the State – the transcription of his audio tapes – that Deng felt that they had been too lax with ideological work.

So early on, in ’87, maybe end of ’86, there had been student protests then followed by the anti-bourgeois liberalization campaign and the anti-spiritual pollution campaign. It’s right when I arrived in China. I was a little bit nervous about that. But the people, they were like, “Oh, don’t worry about it.” I was in Tianjin. I spent the first six months in Tianjin and the teachers and the folks that I interacted with in Tianjin were like, “Oh, don’t worry.”

I’d see signs up everywhere about anti-this, anti-that. Essentially anti-western kind of everything. They [the people] would just say, “No, you’re so welcome here. Don’t worry. Don’t pay attention to any of that. We’re not paying attention to it.” So basically Deng was like “this [Tiananmen] is because of lax ideological work.” So we see now 30 years later, Xi Jinping, you cannot say that he’s lax.

CL&P: Yeah. He’s anything but.

Current Chinese President Xi Jinping (L) – is he just a little Mao?

AW: He’s anything but. Right. Over the years, since 1989, there have been moments that were a bit more open. But the overall trend has been “not lax.” And control of information of course, censorship as the internet grew, of course media censorship – so not lax.

So there’s that aspect of essentially political education and indoctrination, ideological education. We see that now tenfold, a hundred fold in Xinjiang with what’s happening with the Uighurs. They’re in concentration camps, probably 1.5 million all told and very much of this is about political education, forced education among other things. So forced ideological kind of education. So one aspect is this, that we have to sort of control information, control thought.

But there’s also just the physical, this physicality, if you will, of the protest. Now it’s physically impossible with all of the surveillance cameras and everything. They want to prevent you from even having the thought of protesting. That’s what a lot of the ideological education is about. And also of course everything is watched and surveilled. So you can’t even mobilize people, like five people. . . . it’s very difficult to mobilize even five or 10 people to do anything. So, it’s extremely hard to imagine a scenario where people are back on Tiananmen Square.

Also, of course another lesson was we need to train people’s armed police, armed forces. We need to be able to also have trained police, quasi-military forces, whatever, to deal with anything that might happen. Like essentially riot police, if you will. So they’ve got that whole aspect of things totally also nailed down.

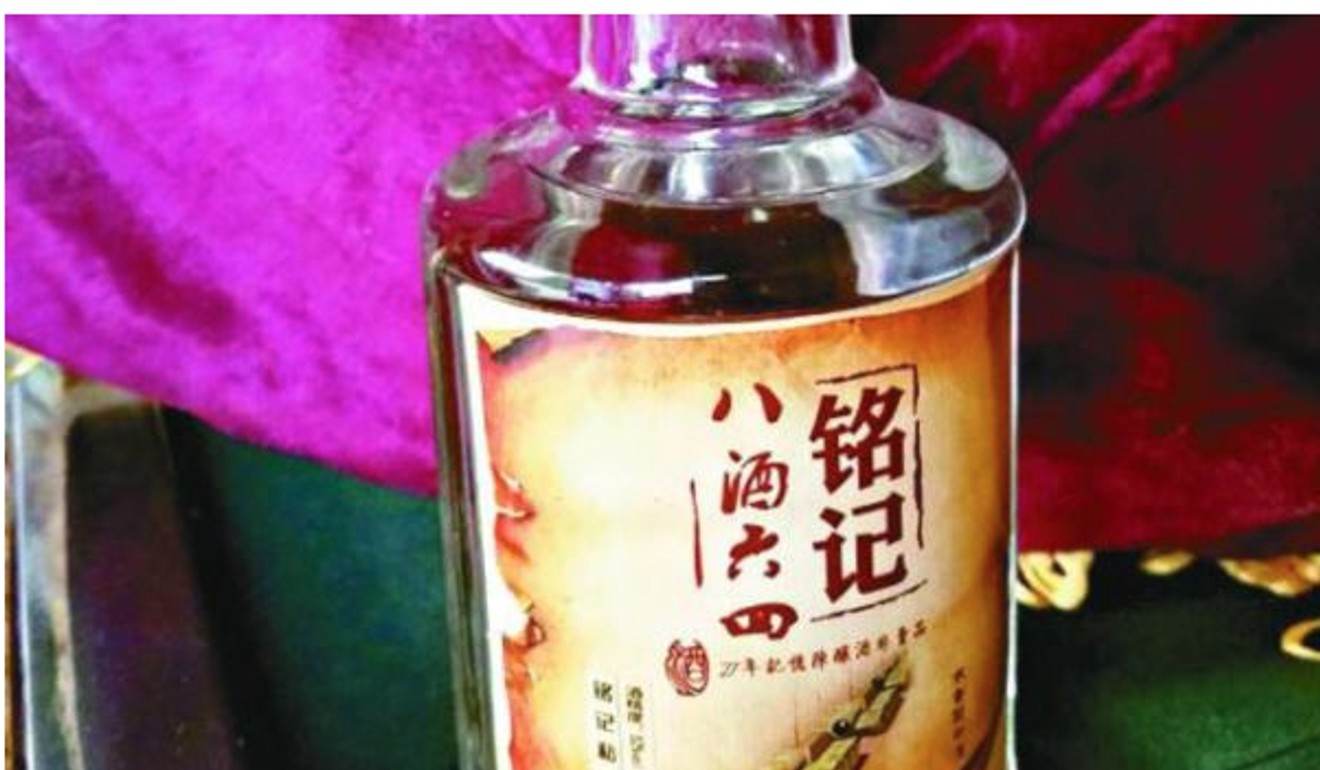

Obviously we do see these sort of spontaneous or very small efforts here and there, but they’re immediately shutdown. So I think no more Tiananmens is of course a big legacy, and no little Tiananmens in terms of the protest. Then also of course in terms of the legacy, this is such a sensitive issue for the Communist Party, this whole period, particularly the massacre and the incredible spin they put. The story they’ve told that they continue now 30 years later to detain people who might mention June 4 or write something trying to commemorate June 4. One recent example is the folks, the four people in Chengdu I believe with the June 4 liquor labels. [Ed. Note: In 2016, a few people in Chengdu created a liquor label for a few bottles of Chinese rice wine – called “bai jiu” – a sound similar to the word for 1989 – “ba jiu” – with pictures of a man stopping a line of tanks. These men were arrested for subverting state power and were recently sentenced.]

CL&P: Yes. Yes.

The baijiu bottle that resulted in arrests and sentences for four indivduals

AW: I think it was even like one bottle. Then it was like three-year or four-year sentences for that.

So, it’s that level of insecurity, of absolute intolerance toward any sort of expression around June 4 and commemorating the dead, those who were killed. Some have also called to re-designate those protests as patriotic and as not turmoil, something that is going to continue to be something that people will continue to call for. But the CCP, I can’t imagine them really doing that. It would seriously have to be major political reform for that to happen. But one day I’m hopeful, one day that that will indeed happen. [Ed. Note: Rights Lawyer Teng Biao echoed a similar sentiment in his interview: that the Tiananmen protests will not be remembered on mainland China unless there is significant political reform. For him, that is democracy in China.]

And that particularly I wanted to also just mention the group The Tiananmen Mothers. [These are] family members who lost loved ones in Beijing June 3 and 4 in 1989 and who have just been an amazing force to try to uncover – because the Chinese government isn’t and is trying to suppress this information – trying to uncover the names and identities and sort of details about who was killed that night. They’re still at it. They’re calling for an investigation, for compensation and for an apology. Anyway, it’s important to also honor their efforts and their loss.

CL&P: Yeah. Well, I want to thank you and also echo your sentiments that there’s still a lot of brave Chinese that are still trying to commemorate what happened on June 4th and the bravery of their fellow citizens. But I want to also thank you for also writing down your stories and remembering for the Chinese people who can’t right now develop their photos of what happened during that time period and commemorate it in the way they can. So thank you again, Andréa for sharing and do you have any last words?

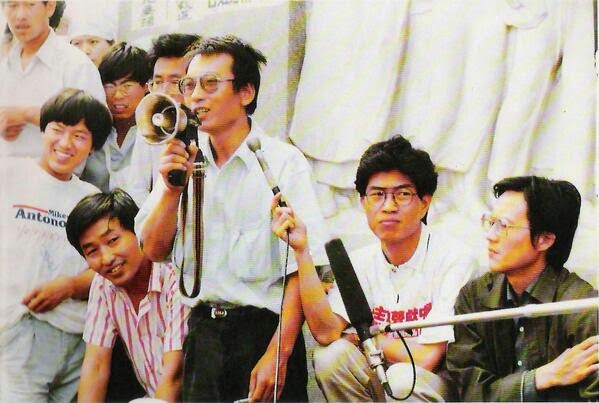

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) protesting at Tiananmen, spring 1989. He would latter be sentenced to 11 years for participating in 2008’s Charter ’08 and would ultimately die will serving his term.

AW: Yes. Thank you so much. Although it’s a grim topic, if you will, I appreciate the opportunity to sort of share this with you. I do actually want to end on another note of hope, which is that another legacy of Tiananmen is also those people who continue to fight for democracy and human rights in China. For example, Charter ’08 and the Charter ’08 Movement, Liu Xiaobo and many others, many of the human rights lawyers, there is a direct line from 1989 through Charter ’08 to today.

So a lot of the activism is happening outside of China now, but there still are activists in China doing what they can in the very limited space that they have to essentially fight for human rights, for rule of law, and political freedom.

CL&P: Yes. Thank you for reminding us of that.

AW: Okay, thanks, Elizabeth.

CL&P: Thank you.

***********************************************************************************************************************

This ends China Law & Policy’s interview series, #Tiananmen30 – Eyewitnesses to History. If you missed our interview with Frank Upham who was in Wuhan in May and June 1989, please click here. If you missed our interview with human rights lawyer Teng Biao, who recounted the indoctrination he received after Tiananmen and then his awakening to the truth, click here.

Never forget the murder, but more importantly, never forget the hope

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email