Late to the Party? The U.S. Government’s Response to China’s Censorship

Part 3 of a three part series on American journalists’ difficulty in obtaining visas to China. For Part 1, click here; Part 2, click here.

When China denied veteran journalist Paul Mooney’s visa request this past November, neither the State Department, Administration officials nor anyone on Capitol Hill said anything publicly about a U.S. citizen appearing to be punished for his speech.

Similarly, when China failed to renew U.S. citizen and Al Jazeera English correspondent Melissa Chan’s visa, forcing her to leave China in May 2012, a State Department deputy spokesperson merely expressed the Department’s “disappointment” very briefly during a regular Q&A session with the press: “I would just say that we’re disappointed in the Chinese Government – in how the Chinese Government decided not to renew her accreditation. To our knowledge, she operated and reported in accordance with Chinese law, including regulations that permit foreign journalists to operate freely in China.” Such has been the extent of the Administration’s public statements, until now.

It is certainly a positive development that Vice President Joe Biden, on his trip to Beijing last week, publicly rebuked the Chinese government for its treatment of U.S. journalists, tying Beijing’s actions to impacting “universal human rights.” While the comments at last Thursday’s closed-door meeting with U.S. journalists were off-the-record, the fact that the meeting occurred was very much on-the-record, demonstrating that the Administration has finally realized the seriousness of the situation and the need to try a new tactic.

But one wonders if the Administration’s changed strategy – publicly addressing the issue – is too little too late. According to reports, the Chinese

government is still toying with the visas of approximately 24 New York Times and Bloomberg correspondents; without renewal by December 31, the New York Times and Bloomberg’s China bureaus could potentially shut down, much in the way Al Jazeera English‘s Beijing office had to close, over a year and a half ago, when Melissa Chan’s visa was not renewed before its expiration.

Why the U.S. Government Must Act – Protecting an American Brand

A free and vibrant press has been a central tenet of the United States; it was crucial to the success of the American Revolution, is encapsulated within the First Amendment and rarely if ever abridged.

For Americans, standing up for freedom of the press is important in and of itself, but becomes even more critical when journalists from one’s own nation are being restricted. Congress or the Administration insisting that China allow access to foreign journalists is different from demanding access for other industries; it is not some mere effort to protect the domestic media establishment. Rather, speech is a core value of the American people, and condemning censorship is, as Hillary Clinton put it, part of our “national brand.”

This national brand goes beyond the U.S.’ own borders. As recounted by Chinese journalist Liu Jianfeng in a special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists, it is often the foreign press’ coverage of domestic events that provides the green light necessary for the Chinese media to cover more sensitive issues. Liu specifically points to the 2011 Wukan protests, where over a thousand villagers demonstrated for months because of the local government’s land seizures, to make his point. It was only because the foreign press started covering the event that the Chinese media was permitted to do so. Similarly, Melissa Chan filmed her report on China’s black jails in April 2009; in November 2009, a Chinese magazine ran a similar expose. In February 2013, signaling official opprobrium, a Beijing court sentenced 10 men to prison for illegally operating a black jail. Thus, the U.S.’ promotion of freedom of its press in China benefits the Chinese people, bringing some accountability and transparency to their one-Party state.

Not Just a Moral Principle But Also Good for Business

China’s attempted censorship of the foreign press – through its abuse of the visa process – certainly infringes upon free speech. But there is a more mercantile reason to guarantee that U.S. media companies are not censored: information and disclosure are key to efficient markets. Accurate information protects investors and businesses as it creates transparency in the market, placing all sides of a transaction on equal footing. This is especially true where an economy, like China’s, is particularly opaque.

China’s attempted censorship of the foreign press – through its abuse of the visa process – certainly infringes upon free speech. But there is a more mercantile reason to guarantee that U.S. media companies are not censored: information and disclosure are key to efficient markets. Accurate information protects investors and businesses as it creates transparency in the market, placing all sides of a transaction on equal footing. This is especially true where an economy, like China’s, is particularly opaque.

One of the apparent red lines for foreign reporters is the finances of China’s leadership: the New York Times‘ David Barboza wrote an October 2012 series concerning former Premier Wen Jiabao’s protection of his family’s investment in Ping An Insurance and Bloomberg published its June 2012 “Revolution to Riches,” an expose on the children of China’s revolutionaries and the power and wealth they have been able to accumulate. Both have also become Beijing’s main targets.

What Beijing currently seeks to censor – articles about the overlap of its economy, major businesses and the power elite – are the exact articles

necessary to inform potential market investors. Unfortunately as the New York Times and Bloomberg reporters appear on the cusp of a compelled departure, there are few news agencies that can – or will even want to – fill their role of hard-hitting financial reporting on China, a time-intensive endeavor.

But even articles about legal development, political unrest, growing wealth inequalities, environmental degradation and crackdowns on dissent, issues that Mooney and Chan fervently covered, are also important. Businesses who invest in China hire companies – like the Eurasia Group – to inform them about these developments. It is vital to their investments to know if the village, town or county where their company or factory is located is a political powder keg.

But by continuing to harass, intimidate and effectively expel journalists who cross certain red lines, Beijing is sending a message to the remaining reporters. “The decision to deny Paul Mooney a visa has brought home to our membership the lengths the Chinese authorities will go to persuade foreign reporters not to report on things they don’t like” Peter Ford, president of the Foreign Correspondents Club of China (“FCCC”) told China Law & Policy in a phone interview. Foreign reporters who are left in China may not want to continue to take on these hard-hitting stories that could effectively terminate their livelihoods. Their editors may not let them. As a result, banks, investors and even the U.S. government will lose one of its most important resources for accurate and frank reporting on a country vital to America’s position in the world.

‘It’s Only Words’…Or is it Visa Retaliation?

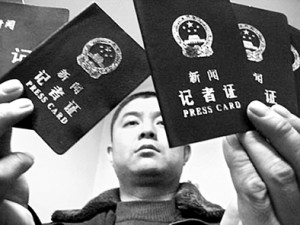

Right now, approximately 24 foreign correspondents for the New York Times and Bloomberg are waiting for their visa to be renewed. According to reports, many have not received their press cards, the annual cards issued every November by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (“MOFA”) and necessary to apply for a visa renewal with the Public Security Bureau’s (PSB) Exit- Entry Administration. Under China’s new Exit-Entry Administration Law, resident foreigners, such as foreign journalists, are required to apply for a visa renewal at least 30 days prior to the current visa’s expiration (see Article 32). In China, all journalists’ visas have a December expiration which could be any day in the month, with the 31st as the last. Since it is already December 8, those journalists who have not received their press cards, are currently in violation of Chinese law. However, as Gary Chodorow, a Beijing-based immigration lawyer, points out, the law is silent as to any repercussions to applying late. But that is of little comfort to those reporters unsure if they will have to leave China on or before New Year’s Eve.

“Things are never going to get better if we don’t do something reciprocal” Mooney complained to China Law & Policy last week in a phone interview and prior to Biden’s Beijing visit. “Some sort of stronger tactic would be helpful” Mooney said.

“Things are never going to get better if we don’t do something reciprocal” Mooney complained to China Law & Policy last week in a phone interview and prior to Biden’s Beijing visit. “Some sort of stronger tactic would be helpful” Mooney said.

But is Biden’s public censure last week and meetings with journalists sufficient to stop a Chinese government that appears intent on essentially shutting down two major U.S. media outlets in China? Even in light of Biden’s actions, the Chinese government appears to have dug in its heels with a MOFA spokesperson stating on Thursday that “[a]s for foreign correspondents’ living and working environments in China, I think as long as you hold an objective and impartial attitude, you will arrive at the right conclusion.” “Objective” was the same key word used in Mooney’s visa interview before his visa application was denied.

This type of stubborn behavior is precisely why some have begun to consider reciprocal visa treatment as a way to deal with China’s attempted censorship of the foreign press.

The U.S.’ Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA”) provides journalist visas “upon the basis of reciprocity” (see INA Sec. 101(a)(15)(I)). Reciprocity is a foundational principle of the international order, guaranteeing that the treatment of one country to another will be returned in kind. Reciprocity – and the fear of negative reciprocity – is what induces international actors to act reasonably.

While visa reciprocity is usually in regards to fees and other procedural aspects, reciprocal treatment can be used to deny entry to a foreign national. The INA also permits the State Department and its consular agents to deny a visa where entry of the individual would have “serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States….” What is a “serious adverse foreign policy consequence” is left in the discretion of the State Department and its employees. In fact, the decision to deny a visa falls under the “Doctrine of Consular Non-reviewability” and is rarely subject to judicial review (exception: Kleindienst v. Mandel, 408 U.S. 753 (1972)).

With the U.S. issuing 989 journalist visas to Chinese mainland reporters in 2012, many of which are issued to Chinese state-run media outlets,

some have looked to deny one or two key visas as a form of reciprocity. At the very least, some have suggested slowing down the visa approval process much in the same way the Chinese government does to U.S. journalists in China.

While legal, it raises the question of is this who we want to be? The reason why the U.S. government should more publicly reprimand Beijing for its treatment of foreign journalists is because of the U.S.’ commitment to freedom of the press. For the U.S. to refuse a visa to a Chinese journalist would undermine that commitment. While many of the Chinese reporters do work for the state-controlled media, they are still journalists and should be protected by freedom of the press. These also are not the individuals responsible for the Chinese government’s actions.

The U.S. government, in calling on China to stop censoring its reporters through the visa process, has the moral high ground. Because of the principle of freedom of the press, the U.S. government is seeking to guarantee that its media outlets – outlets that often run critical stories on these same politicians – are able to report freely from China. Even if not reported in the Chinese press, this type behavior still resonates with the Chinese journalists both in the U.S. and in China.

If the U.S. government were to resort to visa reciprocity, it should not look to restrict or delay Chinese journalist visas. Instead, visa denials or delays of employees of MOFA or the PSB, the entities that are responsible for U.S. journalists current mistreatment in China, is likely more appropriate. Visa denial of responsible government officials would not be a first. The U.S. currently has a visa ban on approximately 128 Zimbabwe government officials and their families. These high officials have been deemed to be partially responsible – along with President Robert Mugabe – in undermining Zimbabwe’s nascent democratic practices. As a result, the U.S. has targeted them with visa denials

‘But Words Are All Have’…Other Options Open to the U.S.

There are still less extreme courses of action that the U.S. government can take. Biden’s public statement in Beijing and meeting with U.S. journalists were a start. Public admonishment of China’s behavior must continue and be regular. In speaking with China Law & Policy, Ford, president of the FCCC, an organization which does not support using visa retaliation, stated that “the FCCC does not think it would be inappropriate for foreign diplomats to take every opportunity to remind their Chinese counterparts that Chinese journalists face none of the obstacles that foreign reporters in China are faced with. ”

In the U.S., this reminder must come from both Congress and the Administration. Although Mooney has reached out to members of Congress, including his representative, Nancy Pelosi, Capitol Hill and the White House have remained largely silent other than Biden’s recent remarks in Beijing. China Law & Policy‘s calls and emails to Representative Pelosi’s office went unanswered.

Fortunately, to keep this issue front and center, the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (“CECC”) will host a roundtable discussion

this Wednesday featuring Mooney, Bob Dietz, Asia Program Director at the Committee to Protect Journalists, and Sarah Cook, Senior Research Analyst for East Asia with Freedom House. How well attended that roundtable is will signal to Beijing just how far it can go in its abuse of the journalist visa process. Biden’s gestures in Beijing were an important start but will senior Administration or State Department officials attend the roundtable? Will it be more than just Congressional interns in attendance? China knows how to read Capitol Hill tea leaves as well.

There is a chance that the New York Times and Bloomberg reporters will have their visas renewed and the China bureaus will not be shut down. But while the immediate crisis might be avoided, as this series has demonstrated, Beijing will likely continue to find ways to censor foreign reporters through the visa renewal process or through direct pressure on the editors of key newspapers. The fact that this has risen to crisis level means that the U.S. government did not act boldly soon enough to protect one of its core values, freedom of the press.

This is the third and final post in this series. To re-read Part 1, click here; Part 2, click here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email