Excerpts of this Interview Originally Posted on the Huffington Post.

I read lots of books about China, it’s what I do. But there are few that I anxiously await for as much as Peter Hessler’s new

Photo Credit: Robert Burnett of www.rburnettjr.com

book Country Driving: A Chinese Road Trip . His last book – Oracle Bones: A Journey Through Time in China

. His last book – Oracle Bones: A Journey Through Time in China – was brilliant and is usually the book I recommend people read when they want to learn more about China. But now there is Country Driving which equals, if not surpasses the elegance of Oracle Bones. In focusing on everyday life in the villages and factory towns for the past ten years, Hessler watches a China transform before his eyes, and in the areas most impacted by its modernization. While Oracle Bones showed a China dealing with the ghosts of its past, Country Driving shows a China wrestling with the demons of its own development. If you want to understand today’s China, and the forces changing it, you need to read Country Driving.

– was brilliant and is usually the book I recommend people read when they want to learn more about China. But now there is Country Driving which equals, if not surpasses the elegance of Oracle Bones. In focusing on everyday life in the villages and factory towns for the past ten years, Hessler watches a China transform before his eyes, and in the areas most impacted by its modernization. While Oracle Bones showed a China dealing with the ghosts of its past, Country Driving shows a China wrestling with the demons of its own development. If you want to understand today’s China, and the forces changing it, you need to read Country Driving.

I sat down with Hessler to discuss his new book and his thoughts on China – its problems, its future, its people. How have things changed? How have the people responded to these changes? What is the impact of rule of law in China? Is China the overwhelming power that the West currently makes it out to be? Below is an excerpt of my interview with Hessler.

To listen to the interview, click here.

For a PDF version of the transcript, click here.

**********************************************************************************************************

Hi, this is Elizabeth Lynch of China Law & Policy.com and welcome to our podcast. Today we are here with author Peter Hessler to discuss the release of his new book, Country Driving: A Journey Through China from Farm to Factory. This is the third book Peter has written about China. The first, River Town, tells the story of his two years teaching English in a small city in Sichuan, China. His second book, Oracle Bones: A Journey through Time in China was a 2006 National Book Award finalist and a New York Times Notable Book of the Year.

Thank you for joining us today.

EL: My first question is just about your stay in China. You first arrived in China in 1996 to teach English in the Peace Corp and you ended up staying there for 10 years. What is it about China that kept you there?

PH: I guess it’s a surprise to me because it wasn’t a place I was interested in growing up and when I was in high school and college I certainly never studied Chinese or anything about Chinese history. And actually when I was in college, it wasn’t that common for people to study Chinese in the late 80s, early 90s. Actually, the first time I went to China was 1994. I finished graduate school in England and I decided to go home to the east and take a long trip around the world. I was really interested in seeing Eastern Europe and Russia and I was with a friend and we figured we would go through China and to Southeast Asia. Really I didn’t have much interest in China; I hoped to get through China quickly in that trip; people that were coming in the other direction said bad things about it – it wasn’t very easy to travel in – so it really wasn’t a place I was looking forward to.

We took the train from Moscow to Beijing and I arrived in Beijing and I was really sort of blown away by the place. There was just a very tangible energy on the street; you could just tell that things were happening, people seemed motivated. It was quite a contrast to what I’d seen in Russia which at that time – this was in 1994 – I found a little bit depressing. So it really surprised me and so I ended up extending that trip. I think my friend and I spent maybe close to two months total in China. We didn’t speak any Chinese; we were just bumbling through as backpackers basically. But it really did grab me.

I had always intended to apply to the Peace Corp but this changed my plans in that I applied to the Peace Corp but I really wanted to go to China. I think that in the end, that energy that I sensed from the first week I was there was what ended up keeping me in China so long. When I did join the Peace Corp in ‘96, I had a sense that it might be longer than two years. Because I had been there and because I knew it’s a big deal to try to learn a language like that and to try to understand a place like that, I knew that it would take more than two years basically. So I wasn’t surprised in some ways that it ended up being longer; I guess I wouldn’t have expected it to be a decade, but there was never a time…I never got tired of the place. You certainly never feel like you know everything; for one thing, everything is change so even if you did by some miracle you know everything, it’s going to be different next week.

EL: In your new book, Country Driving, a lot of your stories focus upon you driving around China, getting your driver’s license, and the car plays a very significant role in your stories. How did you decide to focus on the car and driving in China? Was it a purposeful choice or was that just how the story developed?

Elizabeth Lynch interviewing Peter Hessler; Photo Credit: Robert Burnett of www.rburnettjr.com

PH: Usually when I do projects, I try to keep them very open-ended. Actually with all of my books I’ve actually written a book and worked out a contract afterwards. So I don’t like the idea of having to propose something before I do it because basically you don’t know what’s going to be there. I like to respond to the material.

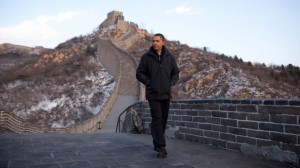

Basically this started as a magazine story while I was doing a piece for National Geographic on the Great Wall of China and I decided I wanted to drive along the Great Wall. The trip became more and more ambitious as I was planning because I liked the idea of doing it. I thought it would be interesting, I had just gotten my license. And then that journey was just a great experience; it was probably the best trip I have every taken in China. And after taking that trip I started to think, I would like to write about this in a book but I really feel like there are these other issues I would like to explore. One of the things I noticed while I was driving across is that you go through all these little villages, where people are leaving and life is obviously really different from what it was 10,15,20 years ago. I wanted to get a deeper sense of what that meant to people and how people respond to that.

Around the same time I was renting a house outside of Beijing in the countryside mostly just for personal reasons, just because I wanted to escape from the city, but I eventually started writing about that place and how people cope with the changes.

And as time moved on and I had these two parts of the book, I was thinking about, I realized I need also to give people a sense of where all this is going, all these people are leaving the villages, young people are migrating, they are going to these factory towns, I want to write something about a factory town as well and have this in the book. You know, for me this is the way projects have generally developed. You sort of feel your way along and you get to a point and you can sort of see the whole thing in the sense of what you need and what you would like to do. And for me that was at the moment when I said okay, I want to go to a factory town and write about development there. And once I got into that last project, which was in Lishui, I could see that that would be the book basically.

As far as the automobile, there was a link to all of them because the first one was a driving trip that kind of gave me an introduction to the north and to some of these rural issues; the second journey was to a village where they didn’t have a paved road when I started going out there and renting a house, and eventually they paved the road, there was a car boom in Beijing and this place responded very dramatically, people’s lives changed in enormous ways. And then for the last section, about the factory town, I chose a town in Zhejiang province that was along the route of a new expressway because I knew that this was a highway that linked them to the coast. That has a huge impact on your local economy if you have a road that goes to a port.

EL: The first part of Country Driving, you describe your drive along the Great Wall and you go through a lot of these villages that are, that seem like they are just closing down and they are mostly poor, you talk about them being depopulated, barren, no longer farm-able, and you even talk about some of the aid work there that is subject to a lot of corruption, in your mind, what do you think is the future for these villages? If you go back 10 years from now, will they exist? What do you see for these villages?

PH: It was very striking because China has been in the midst of this incredible migration. Most of the figures now are 130 million, 140 million people have left the countryside – mostly young people looking for jobs in the cities. When I was traveling, it’s amazing how this is the other side of migration; you’ve been to the factory towns or the cities where you see all these people, but where are they coming from? You go to these villages, and I’d drive through, and you talk to people and they would usually say the population is decreased by half, roughly. That was generally the number I would get from talking to people. I never met anybody in a place who said, oh we haven’t lost population. It was every single town.

Often it’s really striking that you just do not see people in their late teens and twenties in these towns, and thirties. They’re either older people, elderly, or you see disabled people or you see small children because children are still being raised by their grandparents often in these villages. So, it was something as I drove….In a way they are quite poor, they’ve always been poor, but they’re also incredibly open and friendly. I never had a single bad experience in these little towns and people were incredibly generous – they would invite me in, they were totally trusting. So it did make me sad to think about that, that these places are really changing. And I don’t know who is going to be there in a generation. It’s hard to envision who, why would someone stay basically, and people often told me that. Along the way I was picking up hitchhikers, which is mostly because I had an empty car and I found that it was interesting, and most of those hitchhikers were young people migrating, and you talk to them and they say ‘there’s no way I am going back, there’s nothing there for me.’

Often it’s really striking that you just do not see people in their late teens and twenties in these towns, and thirties. They’re either older people, elderly, or you see disabled people or you see small children because children are still being raised by their grandparents often in these villages. So, it was something as I drove….In a way they are quite poor, they’ve always been poor, but they’re also incredibly open and friendly. I never had a single bad experience in these little towns and people were incredibly generous – they would invite me in, they were totally trusting. So it did make me sad to think about that, that these places are really changing. And I don’t know who is going to be there in a generation. It’s hard to envision who, why would someone stay basically, and people often told me that. Along the way I was picking up hitchhikers, which is mostly because I had an empty car and I found that it was interesting, and most of those hitchhikers were young people migrating, and you talk to them and they say ‘there’s no way I am going back, there’s nothing there for me.’

So I don’t know what happens. I think maybe eventually if China reforms some of the land use laws perhaps people would consolidate farms and there would be some farmers who could make a better living because they have bigger holdings. That’s what should logically happen. In some ways it’s not a bad thing, because a country….When they started the reforms they had like 900 million farmers or something in ‘78. You don’t really need 900 million farmers in a country. It’s inevitable that this is going to happen. And we’ve been through it, Europe went through it. If you look at 19thcentury literature, there are all these poems, English poems, about villages that are dying and don’t exist anymore. So this is an old story in that sense. I think eventually you will see this consolidation and there will be some who remain as farmers but for this particular moment it is very hard to see the future.

EL: In terms of the law, you brought up some reforms to land use laws. And in certain parts of Country Driving I know you mention, just in passing, the Chinese law and the legal system. Your neighbor in Sancha, Wei Ziqi, he holds onto contracts dating back to the Qing dynasty, showing that he should have title to certain lands. You describe how the law doesn’t protect the countryside and allows cities to buy farmland at cheap prices and then just flip it at a higher price. And you also discuss the petitioning system. When you bring up these interactions with the law, it seems like the law itself doesn’t really offer solutions for the people that you write about. Do you think this is changing at all? Do you see the law or the legal system developing in a way to protect these people? In the field I am in, we hope that the legal system is changing to better protect a lot of these people, but on the ground do you feel that is really happening?

PH: You know, like so many things in China, there are so many levels to this issue. I think there is a huge amount of vitality and energy in the legal field right now in China and if you go to Qinghua University, at the upper end it’s quite vibrant. There are a lot of people thinking very hard about these issues, working very hard on them, there is a lot of life to it. So I do think in that sense it’s clear that there are people that are interested in making this a better system, no doubt. And I think eventually, it will happen.

For this book, really my focus was much more on working class people. A lot of these people were farmers. Basically, most of the people I am writing about are people who are from the countryside but are making this transition in one way or another to urban life or to being entrepreneurs; in the last section, people who are becoming factory workers or managers and so on. So I am sort of seeing their perspective which is going to be very different from a legal scholar.

But it’s interesting, when even in these places, the people have a deep faith in law really and quite an interest. You mention Wei Ziqi, this is someone who had just about eight years of formal schooling but he’s very bright and when he was older and had been farming for a while, he took a correspondent course in law for example. And he kept all of these books that he got from that course that taught him how to draw up contracts for example. So when I rented a house there, he wrote up a very formal contract and had me and the person I was renting with sign it. And it had all these clauses – one of the clauses was that you can’t store explosives in the house – very detailed stuff. It really had no legal status; you couldn’t take that contract to court but he believed….To him it was important and it showed sort of an interest in it and a respect for the law. So you do sort of see that a lot.

I guess my characterization of how….And for him in the village, he was aware of certain laws – like when he wasn’t getting a certain fee he was suppose to be getting, he would find some ways to make sure he did. And he would say the law’s on my side. It was important to him.

I think….One of my general conclusions on how people interact with the law in places like this and in the factory towns is that it is certainly not a fair system and it’s not a system that we would see as certainly as being anything close to finished, but it’s pretty functional to be honest.

You mention the land use issues, which are really unfair to people in the countryside, but it allows development to proceed in the way that it has. In some ways they are at a stage now, it’s a weird stage in that there are huge problems clearly with the legal system. But it works and the corruption even is sort of manageable – it’s almost like there are rules to it and people know how it works. So their level of comfort is a lot higher than what you would expect. As an outsider you think, this is just a bad system, these things are wrong and people shouldn’t tolerate it. But from their perspective it’s different; it’s probably better, it is better than it was 20 years ago. They also know basically how it works. They find ways to make things work in their favor. What they do is not what we would expect.

For example, in the factory town, where I spent a lot of time, there was really very little sense of the law there, in the sense I never met a lawyer there, I never got any sense of anybody doing any kind of NGO work, there’s no unions that I ever encountered. The government had an official union and they would show movies on the street to factory workers – that was the only contact I had with them. But it doesn’t mean that people were powerless. It just meant that they didn’t find recourse in the law specifically. If a worker had a problem, he didn’t talk to a union, he didn’t call a lawyer. But he found other ways to do it.

I write for example about a family that works in a factory. I’ve watched them over a period of years. For example,  when they started working in the factory they sent their youngest daughter with the older daughter’s ID. The youngest one is 15, barely 15, and she isn’t legal to work. But because she has the fake ID she gets a job and then she brings her sister in. Soon enough, the whole family is there. And they end up with quite a bit of power because they have a network of six workers or so who were a huge part of the labor force and they could negotiate as a group. So it’s a place where people have agency, the type of agency they have is not traditional, it’s not necessarily legally based. So as an outsider, it’s very hard to understand, but at the same time, you kind of respect it. When I watch that family, the Tao family, when I watch them negotiate, I didn’t feel sorry for them. They were really good at what they did. I would not want to negotiate with them, I wouldn’t want to be the boss. I almost felt more sorry for the boss sometimes because they were just really tough people. So you sort of admire them, but again you realize that it is not a finished system. But it’s functional.

when they started working in the factory they sent their youngest daughter with the older daughter’s ID. The youngest one is 15, barely 15, and she isn’t legal to work. But because she has the fake ID she gets a job and then she brings her sister in. Soon enough, the whole family is there. And they end up with quite a bit of power because they have a network of six workers or so who were a huge part of the labor force and they could negotiate as a group. So it’s a place where people have agency, the type of agency they have is not traditional, it’s not necessarily legally based. So as an outsider, it’s very hard to understand, but at the same time, you kind of respect it. When I watch that family, the Tao family, when I watch them negotiate, I didn’t feel sorry for them. They were really good at what they did. I would not want to negotiate with them, I wouldn’t want to be the boss. I almost felt more sorry for the boss sometimes because they were just really tough people. So you sort of admire them, but again you realize that it is not a finished system. But it’s functional.

So when you talk about corruption in China, it’s not Nigeria. It’s not some country where you go and they just, you try to set up a business and they set up a system of bribes that make it just completely impossible to function. It doesn’t work like that. The other example I give in the book is when these guys are setting up their factory, and the officials from the tax bureau came – I was sitting there watching this whole interaction – these three officials came from the tax bureau. They were intimidating, they let the factory owners know that they were in control, and they sort of had this conversation, this very tense conversation. They asked them questions about the business because they were just starting business and they said ‘do you have an accountant?’ And the boss said ‘no we don’t, we haven’t started selling anything yet so we will get one eventually.’ ‘Well you should get an account.’ ‘Ok, we’ll get one once we start doing business.’ He said ‘no, you should get an accountant now. I have a friend that runs a business that has an accountant and here’s his card.’ And the boss is like ‘oh maybe we should get an accountant now.’ That’s kind of the way it works. That interaction is over and the guy makes a phone call and hires the account. You realize it’s not fair, but it works. It’s not an onerous cost in a way. So he wasn’t angry about it, he’s just like ‘this is the way it is.’ It’s going to cost 80, 90 bucks a month, no big deal, he’ll deal with it.

So, I think that is kind of the stage that they’re at. They do have some huge questions that remain to be answered and it is very hard to tell, especially that land use issue which is that people in the countryside can’t buy and sell their own land. That has been a huge problem over the years and it continues to be. There have been lots of signs and lots of discussions over reform but that hasn’t happened yet.

EL: When you traveling through the countryside and the factory towns, you see a lot of people on the move and you do see these inequities, but amongst the people themselves, what was their biggest gripe? I think a lot of foreign NGOs that are in China, a lot of the work I do, there is a focus on the inequities in society or the environmental damage, things like that. But do you feel that people that are in the countryside and in the factory towns, what do you think is their biggest issue?

Photo Credit: Robert Burnett of www.rburnettjr.com

PH: It’s very localized and if you ask people, it tends to be corruption and what they mean is corruption of local officials. That doesn’t mean that the top levels aren’t corrupt, they just don’t see it. So often they continue to have a faith that the top levels of governments are better run and the people are more honest but the locals, because they know the locals, they see what is happening, they are very cynical about that. It is incredibly localized. One of the years, the year that I wrote about where I was following a dam project in this book, they reported something like 87,000 public disturbances, protests in China that year. And you should see these figures. Every year it’s a figure like that, close to 100,000 and you think my God, the country is about to explode. But when you do sort of encounter one of these instances and look at it, it tends to be so incredibly localized and it’s not connected to larger issues.

So you meet someone in the countryside and you ask them what’s wrong and they won’t tell you the land or the Constitution just isn’t fair in terms of land use laws. It’s hard to have that kind of vision, they’re not seeing these sort of huge issues. What they would tell you is my piece of land, I didn’t get the market value for that piece of land, and that’s really all that they are going to care about, about their own situation. So you don’t see people making these connections. You see some of the outsiders and the NGOs, folks like that are in different positions. But the people that are in the villages, the factory workers, that’s not their issue.

To be honest, it’s such a demanding society, everybody is coping with so much change I often feel like they just don’t have the energy to go after those big issues. You can’t blame them; they’ve got a lot of stuff to take care of. Wei Ziqi, he’s trying to shift from being a farmer to being a businessman, he’s trying to join the Party in the local village, he’s trying to get a solid political position in his village. He has all of these things to worry about, the last thing he’s going to worry about is trying to reform the Constitution. He has no way to do that and it’s just not going to be his natural response.

I think again this sort of contributes to the stability, the basic stability that I see in China. There are a lot of complaints, but again, it’s sort of a pretty functional system. And I never feel….My general sense is not that this place is about to explode. I guess I don’t have that feeling. I’m sort of going in more of a survey approach; I don’t look for problems and then focus, like, in the village. I just went to the village and spent a lot of time there – and so you see what happens. And the same thing in the factory town. I went to this factory town and spent a lot of time there. So I noticed what type of protest came up, but I wasn’t picking the biggest protest in the province – which really makes a big difference if you are a journalist or a social scientist. China is a big country, you can find anything you want. In some ways, this is a more representative approach in the sense of trying to just go to a place and see what’s happening there in a normal situation. I noticed there are a lot of protesters. One significant big issue in the factory town which was the new dam that they were building. But the response to that was not very threatening. People’s anger was very localized, they weren’t coordinated with any other kind of groups, it wasn’t like they were linked up with other anti-dam groups in China, there weren’t environmentalist down there. So it kind of makes me feel that the system is basically sustainable for right now.

EL: In terms of those issues, in noting that there is some basic stability and even though there are these complaints, they are very localized and they’re not becoming a big issue. But if every rural area is having similar complaints, even though they are not unified, do you think that perhaps maybe China is not as powerful as the West right now currently views it? Do you see…Even though it is a stable system, there is a lot of I guess tension on the local level, do you see this as problematic and do you think the Chinese national government is going to deal with it in the future? I guess what do you see for the future?

PH: It’s always a bad game to predict China’s future basically but I think basically, I suppose it’s en vogue to talk, we hear about how overwhelmingly powerful China is. I tend to sort of temper that. I don’t see China as on the verge of collapse, I’ve never felt that at all. But I also don’t see it as this place that is an unbelievable juggernaut, that they are doing everything better than everybody else is doing. There are a lot of problems with the system, there are a lot of flaws. But there are still a lot of safety valves as well.

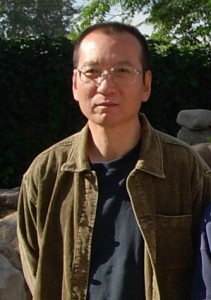

One of the things I write about in this books is what happens to people who could potentially be dangerous maybe to

Photo Credit: Robert Burnett of www.rburnettjr.com

the government, who could cause a lot of trouble. You go to the villages, and the really bright people, the ones who would probably be the most angry about injustices and also the most capable of fighting something or resisting something, they leave, they become migrants because they’ve got opportunities. So it’s like a pressure valve. So you don’t see the really bright young person staying in the village and stirring up trouble. That person is trying to find his way in a factory world. So they have a whole other series of challenges to go. They’re outside of their home community, they don’t have their networks anymore, so politically, they’re not in a position to do a lot.

In the village that I wrote about, the person I knew, Wei Ziqi, he’s one of the very few really bright people who stayed. And what happens to him? Well he has some power struggles with local authorities but he ends up becoming a Party member; he sort of becomes to some degree part of the local power structure. This also happens – people get recruited. So I think there are a lot of different pressure valves basically that sort of take some of the talented people out of the position where they would potentially cause trouble.

It’s sort of a hard thing because it can be very depressing in a way, like when I was in that dam community and I met a lot of folks there who were angry, petitioning, and bitter about it. I noticed that they generally tended to be the lesser educated and they had the fewest financial resources, and this is partly because they were the ones who have been treated the worst, but they also were, I have to admit, also some of the least capable of really doing something basically. And the people I met who were capable had either left or they were finding other ways to make their way. There was one guy in that dam community that was really sharp. When he talked to me he wanted to know what my journalist accreditation was, he had all kinds of questions about what kind of writing I do, he was the first one I met who was really sharp like that and really knew a lot of the issues and his vision was much broader in the sense that he’s like ‘they are moving people from these towns, there is nothing for them to do in these towns, they’re just building these towns and there’s no farming, there’s no business, there’s no factories.’ But he was well dressed, he had a cell phone so I asked ‘well what do you do, how do you get your money?’ and he’s like ‘well I sell building materials in the towns that they’re building.’ So he’s profiting in a way, he’s found a way, he’s kind of hedged his bets basically. I just think there is still a level of opportunity that makes it hard for people to justify really, really devoting themselves to protesting.

I think eventually that changes. But you have to reach a point in my opinion, where sort of the middle class, the upper class, the educated people, the ones with a lot of drive, when those people feel like they’re getting limited, because they have the tools. Right now it’s like the people at the bottom I feel like are the ones that really get hammered. And it’s a very sad situation but it’s very natural in the sense that those are also the people who are the least capable of affecting massive political change.

I think something will change with that but I think it is going to have to be when this other group starts to see it as being in their interest to be a little less self-oriented and a little more aware of ways in which the system can be improved. Like I say, you have more and more energy going in this direction, but I think it is going to take time. I never felt that we were going to see a political change in the next five years or something, a major political change. I never had that feeling in China.

EL: On your road trip, as you were driving, when you were driving, were there any cities that you went through that reminded you of St. Louis or any other cities in the United States?

PH: I’m actually not from St. Louis, I grew up in Colombia, in the middle. I’m trying to think. The cities are totally different it feels like in China. They always feel like they were just built yesterday basically a lot of these places, especially when you are in the factory towns because some of them were basically built yesterday – you can see them going up in front of your eyes. So it’s a different world I guess. Especially my driving trip I did, the first one, was in the north and the big city, I think the only really big city I passed through was called Baotou in Inner Mongolia. Which is this weird place because they had they had a huge amount of money that came in from a government campaign, it just felt like a huge metropolis in the middle of the desert. So they have a different feel and they feel like training grounds. Everything is a trial basically in the sense that all of the people that come in from the outside, the buildings have just been built, the streets have just been built. People need to figure it out on the fly.

EL: And what about when you were driving, did you have any driving music that you listened to, anything like that?

Author Peter Hessler; Photo Credit: Robert Burnett of www.rburnettjr.com

PH: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I was on the road for days. I guess I did two trips, this was in two parts. The first part of this book was a journey in two parts and each of them more than a month, that is a lot of time on the road. Yeah, I brought good driving music – Bruce Springsteen, the Clash, and a lot of rap music as well when I am trying to stay awake, to keep myself motivated. It was very fun, I enjoyed it greatly. Also I had no schedule which helps. I think driving in China can be really tough if you go for like 8 hours a day or something. But I stopped when I wanted to, I tried to be careful so I wouldn’t get too tired. It was a blast. I really, really enjoyed it.

EL: Definitely, it sounded like you had a lot of fun, especially on the trip with the Great Wall. But now that you are back in the States and you are now in Colorado and Country Driving is out, what do you see that is next for you?

PH: I’m doing some projects in the States now where I am researching a couple of things around where I live. I live in southwestern Colorado near New Mexico and Utah. So I’m pursuing some things there which has been great. It’s been nice to do a couple of U.S.-based projects, interview people in the States which I haven’t done for a long time.

So I am shifting away from China for a while and I think my wife and I will probably be moving overseas again in about a year or so. We would like to study another language and live in another part of the world, and write about someplace else. We are thinking about possibly the Middle East. We know that we will go back to China eventually because we both really like it there, we’re comfortable there, we still have a house north of Beijing in the village. But we felt like it’s nice to do something different for a while.

For me personally, this third book for me felt like the last, I felt like I was closing a chapter in the sense. To me it was a great final project because I had all kinds of new challenges. I was putting together a lot of the knowledge I had learned over the decade plus that I had spent in China. It felt like a natural stopping point. I never wanted to reach a point in China where I felt like I was repeating myself or using the same type of story or the same type of structures or the same type of research projects over and over. And this to me, each of the three books feels quite different to me and they have different focuses, so it was a good stopping point. And we will be back at some point and happy to do that.

EL: I know for me and I am sure for a lot of other people if this is the closing chapter on your journey with China, a lot of us might be a little bit disappointed. You’re one of, I think, the greatest writers about modern China. But I want to thank you for taking time to talk to us today. Just for our listeners, Country Driving comes out on February 9 and can be purchased at your local bookstore or on Amazon dot com. Thank you Peter.

PH: Thank you. Thank you for talking to me.

Rating:

Country Driving: A Chinese Road Trip (P.S.) , By Peter Hessler (Harper Perennial, February 8, 2011), 448 pages.

, By Peter Hessler (Harper Perennial, February 8, 2011), 448 pages.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email