What’s the T on China’s Social Credit System? – Jeremy Daum Explains – Part 1 of 2

This is the first of a two-part interview with Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, founder and chief editor of China Law Translate and an expert on China’s social credit system. To skip to Part 2 of the interview series, click here.

This is the first of a two-part interview with Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, founder and chief editor of China Law Translate and an expert on China’s social credit system. To skip to Part 2 of the interview series, click here.

China’s social credit system and its implications for citizen and corporate data, has largely been described by the Western press as “dystopian” and “Orwellian”; it has been compared to the British television show “Black Mirror” and the Hollywood blockbuster “Minority Report”- stories of technology out of control. It has been used to show what could come to the West if we are not careful with our technology.

But is that what China’s social credit system really is? We sat down with Jeremy Daum, senior research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, and the founder and chief editor of China Law Translate. At China Law Translate, Jeremy

Yale Law Senior Researcher & China Law Translate founder, Jeremy Daum

has translated numerous government directives, policy pieces and local regulations on China’s social credit system, making him an expert on this emerging system. He has also written a slew of informative articles and has just come out with a podcast that gives a general overview of social credit. But to get a better understanding of China’s social credit, what it is, is it different from the West and what are the real threats within the system, we now turn to Jeremy.

Read the transcript below for Part I of this two-part interview, where Jeremy gives us the background on social credit, explains that there is no “score” and does a deep dive on the judgment defaulter blacklist. Or click the media player below to listen (total time – 42:03).

CL&P: All right. Thank you again Jeremy for taking the time to sit down today to give us the T, the truth on China’s social credit system. I guess let’s start with the beginning.

JD: Sure.

CL&P: What exactly is social credit? When did it come about? Can you give us some background on this idea in China now that its this social credit system?

JD: It’s a big question what it is. I think it refers to a lot of different systems. It’s probably just a working name at this point. But social credit is a lot of ideas linked by the concept of centralizing data to assess credibility, but it’s taking a lot of different forms. I would say that primarily what people talk about, there’s three big parts of it that we could discuss. The first of those is similar to financial credit evaluations in other countries. It’s about trying to make sure the financial credit extends to more and more people.

President Xi Jinping instituted China’s social credit system.

The other is an administrative regulatory system that involves blacklists that we’ve heard about where various agencies put people on blacklists for violations in their fields. The third major area I think we can talk about, is a moral education component of the government trying to extend the concept of sincerity and trust throughout society. We’ve all heard about the extent of fraud and dishonesty that is rampant in some Chinese markets, and I think they’re trying to address that as well. There are other pieces including government transparency [which] is government social credit. I think those three main areas are a good way to think about it.

CL&P: Just in terms of background are there currently national laws, local regulations? What is the law that’s bringing this about, the social credit system?

JD: There’s already quite a bit of authority in effect. Some of it is provisional regulations, but some of it is fully up there. The one that you see cited in media reports a lot is this outline plan – the 2014 through 2020 outline for establishing a social credit system. That, I have a roadmap of that as I call it of my site where I try to just pull out all the action items. Even doing that it comes out as 11 pages of document, just saying all the things it wants to do. But mainly it’s a list by different fields including education, the internet, food safety and what they will do to establish social credit in areas like that. But in addition to that planning outline, a lot of more practical, implementable law has started to come out.

There are blacklists in almost every regulated industry at this point. And rules for how a person gets on those blacklists, how a person gets off those blacklists and how long information remains on them. A few areas have their own local provincial level regulations, which is a high level of authority governing a more comprehensive idea of the social credit system. There’s a lot out there including guiding documents down to very specific implementation rules.

CL&P: On the national level though, you don’t have an actual law, you have a plan, a policy plan?

JD: Yes, at this point we have a plan, but there’s also quite a few normative documents. These are things calling from the National Reform and Development Committee. Calling for the blacklists to be created; calling for each ministry to create its blacklist; calling for the creation of a unified social credit code for both people, natural persons as well as corporations. All of the local rules are usually in response to a national level mandate.

CL&P: Just to clarify, I think there’s been a lot of perception in the Western media about the social credit system and there being a credit score. You mentioned that one of the aspects is this financial credit that’s similar, but does the social credit system itself institute a credit score? I guess for those in the US who are used to a FICO credit score. How is what’s going on here different or similar or. . .?

JD: It’s important I think to address score. A lot of places have shown a three digit number based on the US model. Some people –

CL&P: When you say a lot of places do you mean –

JD: I mean media, media. A lot of media has reported on that. Wired had an article: a three digit score could control your life or determine your place in society. There are scores involved in this, but let’s back up. Even in that financial component, which I call the credit reporting component of social credit. It actually uses a different uses a different word. It doesn’t use 信用,which is usually credit or trust in Chinese. It uses 征信, which is the same 信 but a slightly different word, and I translate it as “credit reporting.” I do that rather than scoring because it doesn’t necessarily imply giving a score even in that context.

For example, right now the People’s Bank of China does have a personal credit reporting system using that 征信. But what they put out actually doesn’t give a score. It’s a list of debts and obligations and asset evaluations, but it doesn’t give an ultimate score. It just gives a data sheet that a lender might be interested in seeing. So with credit reporting private companies might base on some of the data that they get start to give scores that would be useful to people, but that would be a credit product they’re offering to people. That’s what we’re talking about the financial situation. What people are really interested in and what I think is sexy about the idea of social credit is the idea that people are being rated and evaluated in some sort of a holistic way. That actually there is no score. There isn’t even really a holistic evaluation of people in any way.

There are a few local pilots that do give people scores, that do seem to be a sort of “citizenship score.” The idea is this will in some way tell you how good a person this is. It considers a lot of different things like doing charity work and volunteer work. I view those primarily from my main research focus where I’m a criminal procedure researcher and I look to see how state power is used to enforce these lists. What I found is that in all of these point systems, there are no consequences of a “bad score.” There are some minimal rewards for “good scores” – often things like you get your lawn mowed for free or you don’t have to participate in some other mandatory obligation of sorting recycling or something to this effect. There’s some mild benefits. Not dissimilar to what being a model worker or model family used to be in the old days. I would call it more of an educational system. This is part of that educational component trying to convince people sincerity is an important value rather than anything like an enforcement mechanism of any kind.

CL&P: Okay, so it’s just to promote positive behavior and not necessarily to punish negative behavior. It would just be in this sphere of charity work, doing good work?

CL&P: Okay, so it’s just to promote positive behavior and not necessarily to punish negative behavior. It would just be in this sphere of charity work, doing good work?

JD: Well some of them are holistic and are trying to … They would include things like if you had a criminal violation, they would count that in, but what they’re doing with that in that context is making the score that doesn’t have any real negative consequences besides maybe shaming. Which might be there. I’ve seen very minimal. One of the most extreme that I’ve heard about is you got a larger share of communal farming profits if you had a high score in one of these systems. These scores are really a very minimal part of what going on and don’t really have teeth.

Shanghai for example is the example I’d like to raise the most where they do have an app that gives a score. Shanghai is a big modern city. But this app is entirely voluntary. There are no consequences attached to it. But Shanghai is one of the cities with a full regulation, a social credit regulation available. The regulations themselves don’t mention a score, don’t mention this app anywhere in it. This app is just a promotional tool, a publicity stunt at worst, an educational device at best.

CL&P: Going back to social credit in general and the three aspects that you talked about. The financial credit, the administrative regulatory, the blacklisting and then the moral education. When did the Chinese government start with this plan? When was the plan initially rolled out and why are they doing this now?

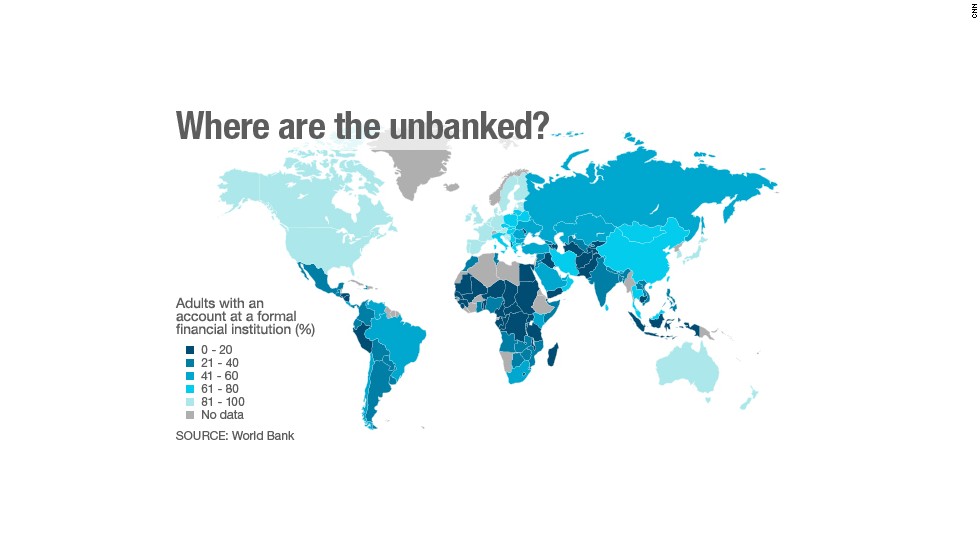

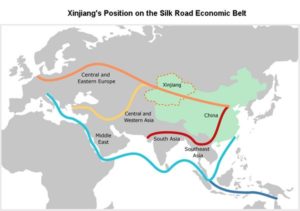

JD: Let’s take it backwards, social credit has existed in a few incarnations. The modern incarnation is really within the span of that plan I mentioned, the overarching plan. Why are they doing it? Well, within the financial credit sector there is still a huge percentage of China’s population, I hear estimates of two thirds, that are the unbanked. They simply do not have a profile in the banking system’s personal credit system. The banks, the government hopes to reach them with credit because a credit economy grows faster, people can have money in two places at once. They needed something to base lending to these people on. If they had never taken out a loan, never bought a house, never had a mortgage, they had to look to other factors. Actually looking to foreign models they had the idea what if we look to some other indicators that this is a good person.

So far, that hasn’t panned out in China. Where the systems, including Sesame Credit run by Ant Financial, that have tried to create an alternative evaluation of a person’s credit as a borrower, ultimately it didn’t seem to be a good indicator of whether they would be good at returning debts and they had a conflict of interest where they were basing it mainly on how much was spent on their own products. That made it even more unreliable. But beyond the financial sector, there is a trust crisis in China. One example that I like to bring up is a terrible story that happened a little while ago at a kindergarten here in Beijing, that I think did make international news. A rumor began that a teacher was injecting students with something. Then this grew into a larger rumor that they were drugging students and sexually abusing them at this kindergarten. It’s every parent’s worst nightmare, of course.

So far, that hasn’t panned out in China. Where the systems, including Sesame Credit run by Ant Financial, that have tried to create an alternative evaluation of a person’s credit as a borrower, ultimately it didn’t seem to be a good indicator of whether they would be good at returning debts and they had a conflict of interest where they were basing it mainly on how much was spent on their own products. That made it even more unreliable. But beyond the financial sector, there is a trust crisis in China. One example that I like to bring up is a terrible story that happened a little while ago at a kindergarten here in Beijing, that I think did make international news. A rumor began that a teacher was injecting students with something. Then this grew into a larger rumor that they were drugging students and sexually abusing them at this kindergarten. It’s every parent’s worst nightmare, of course.

The police then go and investigate. What their investigation finds is that there was a teacher who was in fact pricking students fingers with a needle as punishment, but they weren’t drugging them and there was no real indication of sexual abuse. But from this rumor starting we can see the lack of trust on all sides and how quickly it spreads. The parents were willing to believe that their teachers would do this to their children and then try and cover it up. But they would further believe that the police, rather than have this international embarrassment, would fake an investigation and pretend this wasn’t happening to children in their own country just to make it blow over. There’s the lack of trust on all sides. Nobody trusts anyone. The school can’t trust its parents. No one trusts what the kids are saying and people are ready to believe that the police are engaged in a massive cover-up.

A quicker shorter example would be just thinking of how food safety violations traditionally have happened in China. Not everyone is as high profile as the milk powder scandals of a few years back but product safety in the food area has been a real issue. What used to happen was when you got fined or discovered for these major safety issues, you would simply reincorporate under another name and start doing business. No one would attach this bad will to you or know to be afraid of the products. So people creating shoddy goods could keep doing it in various forms. Part of what the social credit system hopes to do with these real name systems and unified codes is to make it so you can’t escape this record. Now of course that only follows you for a certain amount of time, and you can recover a reputation, but it’s to make it so you can’t just dodge the administrative regulation.

Would you sue your teacher?

CL&P: Just to follow-up on that, that’s interesting because. . . I don’t know that the United States has any more trust than what you have or a lack of trust, but what you do have is a functioning legal system, you have a much more transparent government. Why is the Chinese government choosing to go what to me seems like a much more convoluted route where it’s top-down to impose this trust system as opposed to something bottom-up where, “Well this teacher can be sued, if this was America.” This teacher can be sued for pricking children. You get a discovery, you find out what’s happening and you have transparency with the police and the investigation, you have transparency in the court system. Why is the Chinese government choosing to go what to me just seems like a much harder route to instill trust or to instill a system where trust is. . . where you trust the system?

JD: I don’t think it is a harder route. I won’t get into the reasons why people lack trust except that it’s important in all context to remember exactly how quickly China has developed. The culture has urbanized at an amazing pace. As for American’s trust, I think we actually have an undue amount of trust where I really do believe the FDA has made sure that packaged foods and processed foods that get to me are going to be safe. People from the FDA have told me that might be misplaced faith. Our companies through regulation, but also through litigation like you said, have learned to be more proactive about recalls. Most of the recalls are voluntary, et cetera. Is China taking a harder route to establish trust? I don’t think so.

I think it only sounds that way if you’re overthinking what social credit is again. Because what it really is, is that they’re just making sure. . . and again, this is mainly that middle core of administrative regulations, the most active currently in social credit. What they’re doing is they’re making sure that administrative records, and that primarily includes what they call the double designations of administrative punishments and administrative permits, that those are linked both to corporations by that unique number, but also to the leaders of that corporation, so they can’t just go start a new company somewhere. It’s really just about making the data accessible. It’s not imposing new obligations. It’s not making a complicated new ranking system. It’s really about making that data accessible.

Trying to lift the corporate veil. Will it work?

CL&P: Which is not too far . . . I know working in the United States, working in landlord-tenant, you do see a lot of bad landlords that hide behind the corporate form and are doing horrible things. That’s something we fought for is to try to see behind that corporate form and that we’ve gotten pushed back in the United States. That does seem like a good thing to have greater transparency.

JD: It’s funny because one of the most invasive parts of the actual social credit plans, contrary to what you see emphasized in media reports, is this “through the corporate veil.” The fact that the actual controller, even primary shareholders can be held accountable for the conduct of a company. That could be really risky for individual rights. But what’s interesting is I think that part would actually sell really well to most of the American public.

CL&P: Yeah.

JD: I think that a lot of people have frustration that CEOs seem to walk away with golden parachutes from corporate misconduct. This system does, at least in form, look like it’s made to prevent that. Again, I think the main reason for it here is just to stop the people from repeating their offense in a different form. You see a lot of professional certification bans where somebody who is on a serious blacklist, wouldn’t be allowed to be the manager of a company in that field again after they had a violation. So if I created poisoned powdered milk, I wouldn’t be allowed to open another powdered milk plant within a certain period of time.

CL&P: Right. Right. Let’s go back to the blacklists because I feel like that’s something that has gotten a lot of attention in the Western media too. Can you give a little bit more description, what exactly are these blacklists? Who are making these blacklists? How public are these blacklists? Can you give a little bit more information about the blacklists?

JD: Yeah. Understand the blacklists, which is the administrative regulatory part of the system, which is currently the most active, in my mind by far, part of the system. It’s really a three step thing to understand. The first is real name registrations. Real name applies to when it’s a real person, a natural person. You have to give your real name to get a bank account. You have to give your real name to get a phone. And there’s limits on how many of these things you can get so that you don’t get 20 phones in your name and then give them out to your friends so they are not using their real name. Internet connections, real name. And that’s usually by the way real name behind the scenes. So the company you’re doing it with creates a real name, but if I’m going onto an online service, usually up front I can still use an alias to the public, but they have to have my real name on file somewhere.

CL&P: So you can still be Bunny Honey.

CL&P: So you can still be Bunny Honey.

JD: I can still be Bunny Honey if I want, yes. Everything gets linked back to your real name should somebody need to figure out who’s responsible for something. Now that’s important because that is going to make all of your acts go into a file essentially. Which is why it gets compared a lot to China’s old 档案(“dang’an”) system, the archive system.

The second step is the blacklist creation. All of the administrative agencies were charged with creating standards for who would get put on these lists within their area of regulation. Those standards are when you violate a certain level of law, then we’re going to put you on it. They also in addition to the blacklists have red lists, which are for positive behavior. And they have warning lists, which they call “key scrutiny lists” sometimes. These are for behavior that was negative, but not quite bad enough to get you on the blacklist. The blacklist is usually a pretty high standard. Now again, this isn’t for generalized bad conduct. This is for certain violations within their authority. Often we even say you have to receive an administrative punishment for this.

CL&P: Okay.

JD: What getting on the blacklist does is, and these are industry specific blacklists that each area creates based on their regulatory jurisdiction, so the blacklists though do get centralized on this unified credit platform, which sounds way menacing until you realize it’s a website. What this means is monthly or so they send over the list of people who are to be entered into the blacklist for that particular area. These are searchable. They get released and you can Google or Baidu for them. You see wave one of such and such blacklist, wave two. It used to be easier to find some of them, but now it’s a little harder.

Then the third step of it is the more controversial one, which is that through Memorandums Of Understanding (“MOU”) between different agencies, between different ministries and different regulatory areas, there will be some joint punishment of people who are on the blacklists. Now what I have noticed in reviewing all of these blacklists and MOUs is that the joint enforcement has a few unique characteristics that make it different than the other, sorry than the industry specific punishments. A great example is the No-Fly List. The No-Fly List blacklist breaks down the negative conduct into two distinct types. The first type is aviation misconduct. If you get in a fight with a person at the boarding gate, yeah they’re not going to let you on the plane.

CL&P: That would be the industry blacklist?

CL&P: That would be the industry blacklist?

JD: Exactly. That gets you on the industry’s blacklist-

CL&P: Because you violated a specific industry regulation. In that regard do you get . . . I know you said they’re industry specific, there’s usually an administrative punishment. Will there be some kind of process by which you are informed that you’ve been put on the blacklist, that you’ve been informed you violated the law.

JD: Yeah. Before you get-

CL&P: Industry blacklists.

JD: Right. In most situations an attack on a boarding gate ticket checker is a spur of the moment violation, but usually when you’re being alerted of misconduct they’ll tell you that one possible consequence of this misconduct is being placed on the blacklist. You’ll see that most of the blacklist standards, these rules laying out how the blacklist is created, will actually mandate that. That you have to get this warning. Then you get warned when you’re actually entered on it again. If there’s an administrative punishment involved, you have the normal remedies involved there of having administrative reconsideration or administrative litigation in the courts to fight it.

CL&P: Okay, it’s like if you jump a turnstile on a New York City subway, you get a ticket from the police officer. If you want to fight it you go to the Transit Bureau Court System.

JD: Right. There are in theory ways to be arguing against this, China’s system being what it is, you might find this unreliable. But yes, there are methods. Those in an aviation specific offense that gets you banned from the plane, that’s what could have happened before already.

CL&P: Right.

JD: That’s just the Civil Aviation Administration doing its thing. It has to give a punishment within its sphere of power, and so it’s going to block you for this misconduct.

The second category though that they concern themselves on the blacklist is some of these joint offenses. That includes things like where you’ve been given a securities violations fine.

CL&P: Okay.

JD: Here it’s a little different because it’s not just punitive. It’s not just you get a fine for your securities violation and you can’t ride planes, that’s your punishment. It’s coercive, you can get off of that by paying the fine. It’s meant to make you do something. The most famous example of this and the most commonly confused with being the entire social credit system is the court judgment defaulters blacklist. Part of this is a legal jargon problem that people have mistranslated it. What it literally should be is a list of people who have defaulted on obligations from an enforcement court. What that means is that an enforcement division of a Court has issued a ruling that says, “You have either failed to perform on a court award at a civil trial or you were given an administrative punishment, didn’t pay that fine, didn’t act on it.” Then the administrative organ went to the Enforcement Court and got a court judgment saying-

JD: Here it’s a little different because it’s not just punitive. It’s not just you get a fine for your securities violation and you can’t ride planes, that’s your punishment. It’s coercive, you can get off of that by paying the fine. It’s meant to make you do something. The most famous example of this and the most commonly confused with being the entire social credit system is the court judgment defaulters blacklist. Part of this is a legal jargon problem that people have mistranslated it. What it literally should be is a list of people who have defaulted on obligations from an enforcement court. What that means is that an enforcement division of a Court has issued a ruling that says, “You have either failed to perform on a court award at a civil trial or you were given an administrative punishment, didn’t pay that fine, didn’t act on it.” Then the administrative organ went to the Enforcement Court and got a court judgment saying-

CL&P: – You got a court judgment against you –

JD: – You had failed to fulfill your obligations there. That one has an MOU. The criteria for the blacklist there is failure to perform on an enforcement judgment, which is a single criteria. But because it has court judgment involved maybe, more ministries, more departments, are willing to sign on for joint enforcement of it. It has really wide reaching consequences, including a plane ban, a ban on riding on the best trains, some that I really don’t care for, like your children can’t go to private schools. These are all called limits on high spending or high consumption.

CL&P: Let me just for our listeners that are based out of China. I mean I guess how different is this from what’s going on in some sectors of the United States, right? I know from my practice in New York State if you have a state tax debt of a certain amount, I think it’s maybe about $50,000, I forget, but a lot of people do. Then the New York State Tax Authority informs the Department of Motor Vehicles and Department of Motor Vehicles revokes your license. Is that different? How similar is that to what’s going on here with these joint enforcement of punishments?

JD: It’s the same concept and I think when there’s a court judgment in play, a lot of countries don’t have as much problem having these auxiliary or supplementary consequences to get you to pay. The idea is that you’ve had your due process and now you should be doing it. Sometimes it doesn’t seem to make much sense. Suspending driver’s licenses in the US is going to make it harder for you to earn money to pay back those judgments.

CL&P: Exactly.

JD: In China the idea is that most of these awards are going to be monetary and you shouldn’t be spending a lot of money if you haven’t paid back this award. Your money should be going to fix that problem.

Reading a judgment in a Chinese court

CL&P: Let me ask another question. In the United States when you get a money judgment against somebody you can garnish their wages, you can put a lien on any property they own. You can do a search to figure out what are their assets and how do I get the money out of those assets? Why is that not a system that’s working here in China? Why are they going this route of having this joint enforcement blacklist to enforce court judgments?

JD: They have similar procedures here, it just haven’t proven effective enough. That could be because individuals don’t always have the assets. It could be because they have legal mechanisms for shuffling them around and they’ve tried this as much. But this is aimed to get at the individual. The best way to think about that is if you look at what it’s; the judgment defaulter is a corporation and we talked about going behind the corporate form. Instead of just getting the corporation, we’re going to make it so the CEO’s kid can’t go to private school and the CEO can’t fly on a plane. Now do I agree with that? No, I think that actually has a lot of problems. One of the main problems is it treats all court judgments as equal and I think that say a judgment for me to give a formal apology to somebody or to visit my mom more often on the holidays is very different than an environmental polluter’s judgment to clean up an eco-disaster.

CL&P: Right, right.

JD: I don’t think the consequences should be the same for those. Now the court does have some discretion, doesn’t have to impose all of these exactly the same, but my feeling is that more often than not it’s just they get a blanket restriction on high spending.

What is the impact of the social credit system on China’s farmers?

CL&P: In terms of the high spending, that’s another interesting aspect I think of it is that they just are blacklisting high spending. They’re blacklisting you and it impacts your high spending stuff. It does seem like the repercussions or the targeting is more for rich people or corporations as you said. So to the extent that people captured by this it’s people who fly on planes, it’s people who take high speed rails, it’s people who send their kids to private school. How intentional was that? Because you still, you must have farmers in the countryside that are suing each other that will have a small judgment. Does the law take into blacklisting of them. And how intentional was it to go after people that are more economically well-off?

JD: You’re right, there are limits on high spending and I think that’s because, like I said it’s seen that you should be fulfilling your financial obligations before you get to spend money on pleasure. Of course there’s farmers with disputes between them and people who don’t have means, it may not be as likely that they go through the court system to try and resolve those issues.

CL&P: Okay, that’s true.

JD: I think the crisis and certainly the part that holds back the economy is when it’s larger sums involved. It’s about clearing out these bigger cases. But mainly I think there’s also a feeling that this is in some way just. Like I said, that we’re not going to let you have fun until [you pay]. Now on a lower level there are some places that try things, even with the judgment defaulter list that are along the lines of shaming. That is a mechanism that would work beyond just limiting your own spending, but letting the public know. One place, blanking on where it was, but has it where you’re on the judgment defaulter list when people call your phone, before it picks up, instead of playing a nice waiting music, it plays a message that they are calling a person who is on the judgment defaulter list and they should be careful with you.

People have said that they actually do get pressure from their peer groups from being on this list. I think that would be a great study if someone wanted to look into something about what’s really happening with social credit is whether this is actually working. Are court judgments getting enforced more effectively? Are people not wanting to be on the blacklist. It’s a great area for research. We’ve seen some stuff about public opinion of social credit, but social credit is such an expansive term and really a work in progress as a term that covers so many different programs that I don’t think it gets too much. Whereas the judgment defaulter list is pretty concrete item.

Altercations with flight attendants can get you banned from flying

CL&P: I mean I guess that’s something that you’re touching upon that is interesting too is, yeah, to what extent do people really care if they’re on the blacklist for something stupid. Let’s say. . . to what extent do you think in Chinese society, young people, middle aged people actually care that they might be on a blacklist because they had words with a flight attendant and now they’re on the No-Fly List or something like that. Or to what extent is that a badge of “oh, hey, I had a fight with a flight attendant.” Or when you look in the United States like I know for doctors you can look up how many medical malpractice cases are against them. I always assume there’s going to be one or two because we’re a much more litigation happy society and I don’t really take it to heart. Now if there’s like 20 I might not go to that doctor. To what extent do you think this is influencing or shunning people from society?

JD: The judgment defaulters list, to focus on that, that actually limits enough of your conduct that it’s going to have consequences as its goals. Most of the industry specific blacklists, and these MOUs that enforce them with joint enforcement, limited joint enforcement, I don’t think there’s a risk of anyone seeing it as a badge because what it really is is just you got an administrative fine, an administrative penalty, and they tend to be for fairly serious things, but professional things. The target of that is mainly corporations not individuals and the individuals primarily come into this by virtue of their association with a corporate entity. So being the actually controller, or stockholder, CEO, or the manager for who was responsible for a problem.

It’s not going to be so much even about you, you’re just going to be trying to fix the problem. If you worked for a factory anywhere where the environmental authorities came and said that you were just putting out too much exhaust or waste water and gave you a fine saying that you need to fix this, well that’s not ever going to be something like well I just don’t care. You’re going to have to deal with it. You might do a cost benefit analysis but you’re going to have to address it. That’s really all the industry specific blacklists are. It’s worth repeating that I have seen so far there are no new obligations imposed by social credit, it is just calling the obligation . . . It’s consolidating existing obligations and penalties into a blacklist for the more serious ones and warning list for less serious ones.

CL&P: Has anybody done any studies like. . . let’s talk about the court blacklists which is the judgment default. Has anybody analyzed that blacklist to see how many are just average Joe’s that just got sued and how many are corporations doing bad things and haven’t paid their debts and the people associated with them so the CEOs that are behind them?

JD: Yeah, so there’s been monthly, a really decent analytic reports and they don’t do the full social credit system but they do do the judgment defaulter system pretty well where they do give that sort of breakdown of how many natural persons. Now it’s important to remember that with that piercing the corporate veil aspect we talked about, corporations are going to have natural persons to go on the list with them, but the list for the judgment defaulters is always there and searchable. The monthly report tells you not only how many entities and real persons were put on the list in the month, but how many came off in the month. You can take a look at that at any time. I don’t have the list in front of me but it is a lot of people. I think in September it was over 220,000 people got put on the list.

CL&P: Okay. Just in terms of the corporations and the people associated with it. So what’s going on here on the defaulter judgment list is you’re putting people like the CEO individually and you are, in what we call in the United States, piercing the corporate veil.

JD: Yeah.

CL&P: To what extent, I mean in the United States you can’t really do that, it’s very, very hard to pierce the corporate veil, but here by putting somebody, giving them repercussions, let’s say CEO-

JD: Legal representative or actual controller-

CL&P: Putting them on the No-Fly List, they’re getting the repercussions of their corporation’s bad business-

JD: That’s right.

CL&P: – Bad acts. So to what extent is this creating a new liability for those people, or have you always been able to pierce the corporate veil under Chinese law?

CL&P: – Bad acts. So to what extent is this creating a new liability for those people, or have you always been able to pierce the corporate veil under Chinese law?

JD: That’s a good question. I think this is certainly a new, more direct consequence for them and even for individuals who are owing a court judgment, this is a new enforcement mechanism. Joint enforcement didn’t exist and there’s actually debate in Chinese legal circles if whether it’s legal. Because where’s the authorization for this. I think though even looking only at the judgment defaulters list I think that there’s still very much a live controversy over whether this is allowed towards anyone because where does the Civil Aviation Authority get its power to ban you from flying based on this court judgment, where is that coming from? Do the courts and the Civil Aviation Authority have that power unto themselves?

CL&P: Right, right, right. In terms of the blacklist itself, can you get off of the blacklist?

JD: The judgment defaulter list?

CL&P: Yeah, the court, let’s stick with just the court one because that’s the easiest one.

JD: Let’s call it the judgment defaulter list to make it clear because I know some reporting has thought there was a general credit blacklist that if you fall below a certain something then you’re on a certain magical citizenship list, but this is for judgment defaulters.

Your question was how do you get off it? You can perform, you can perform on the obligation. In theory, you should be able to show that you shouldn’t be on it in the first place. And you can show that you don’t have the ability to act on it because it’s supposed to only apply to people who are willful judgment defaulters. That is, you have the ability to perform but are not performing.

CL&P: If you were let’s say the CEO of corporation X, corporation X doesn’t pay because corporation X is basically bankrupt, you’re on the No-Fly List, you can essentially petition, would it be the court or would it be. . .this is for the court default judgment blacklist. You can petition say look, I don’t have, my corporation doesn’t have enough money, I don’t have enough money, can you please take me off. Is that it?

CL&P: If you were let’s say the CEO of corporation X, corporation X doesn’t pay because corporation X is basically bankrupt, you’re on the No-Fly List, you can essentially petition, would it be the court or would it be. . .this is for the court default judgment blacklist. You can petition say look, I don’t have, my corporation doesn’t have enough money, I don’t have enough money, can you please take me off. Is that it?

JD: That’s right. You would present the evidence in an appeal or a collateral appeal to show that either you’ve already performed and don’t owe this or that you’re somehow ineligible, which would include that you don’t have the ability to perform.

CL&P: Okay, so this is sort like in the IRS, like I know with tax debt, there’s a currently not collectible status for individuals that are so low income it’s like getting blood from a stone and then they can go into that status.

JD: Right, and this would be . . . it seems from this outsider’s point of view that it’s less proceduralized that it ought to be at this point. People have complained about trying to get off the list and get news about where they are, why they’re on the list and had trouble. I don’t doubt that, but I think that’s more of a bureaucratic problem than anything else.

CL&P: Okay, so the bureaucracy is still being worked out and stuff.

JD: Yeah.

CL&P: Here’s another question, what about foreign corporations doing business with China? How does this impact them?

JD: To my understanding when foreign corporations do business here they have to have a legal status here.

CL&P: Right.

JD: When they do, like United Airlines, they have a social credit number attached them. I think foundations as well. Anything that has a legal entity status here, that legal entity is part of the system.

This is the end of Part 1. To read or listen to Part 2 of our interview with Jeremy Daum, click here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email  As China prepares to present its human rights record before the full membership of the United Nations (UN) this Tuesday, we hear the beginnings of a familiar story. Leading up to its third appearance at the Universal Periodic Review (“UPR”)—a UN Human Rights Council mechanism through which each of the UN’s 193 Member States undergoes a human rights evaluation based on recommendations offered by fellow Member States—the

As China prepares to present its human rights record before the full membership of the United Nations (UN) this Tuesday, we hear the beginnings of a familiar story. Leading up to its third appearance at the Universal Periodic Review (“UPR”)—a UN Human Rights Council mechanism through which each of the UN’s 193 Member States undergoes a human rights evaluation based on recommendations offered by fellow Member States—the

Rajagopalan’s Reporting on Xinjiang – Why Is the Chinese Government So Sensitive About This?

Rajagopalan’s Reporting on Xinjiang – Why Is the Chinese Government So Sensitive About This?

Unlike the United States, where there is only one type of journalist visa, Chinese law distinguishes between two types of journalist visas, the J-1 and the J-2. The J-1 visa can only be issued to journalists whose news agency has a permanent office in China (See

Unlike the United States, where there is only one type of journalist visa, Chinese law distinguishes between two types of journalist visas, the J-1 and the J-2. The J-1 visa can only be issued to journalists whose news agency has a permanent office in China (See

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58619791/915205050.jpg.0.jpg)

Since 2004, it has been

Since 2004, it has been