The Obama Visit to China – What the U.S. Press Missed

Originally Posted on the Huffington Post.

Originally Posted on the Huffington Post.

Beijing, China – The U.S. press has not been kind to President Barack Obama and his recent visit to China. Claiming that the U.S.’ tone has become conciliatory toward China, that the trip “yielded precious little” and even oddly comparing the Obama Administration’s behavior on the visit to a one-party, authoritarian regime, the U.S. press has all but designated the trip a failure.

But the trip was most certainly not a failure and in many ways fulfilled the U.S. press’ predictions – an event filled with a huge agenda covering a multitude of global issues, likely offering few deliverables, and probably playing down, at least publically, human rights.

So if the trip confirmed the press’ earlier predictions, then what’s got their panties all in a bunch? Perhaps the one thing that upsets the press more than anything is a lack of access, and on this trip, the press certainly played second fiddle. Questions were not taken from the press during last Tuesday’s press conference and very little other access was offered to the President. But with only a day and a half in Beijing, this trip was not really about the press.

But in measuring President Obama’s trip based solely on their access, or lack of, the U.S. press has failed to report on some pretty substantial results of President Obama’s trip to China. In what you likely will not find in other media outlets that are still licking their wounds from an alleged snub, below are some of the surprising deliverables from the visit.

1. Increased Military-to-Military Contact and High Level Military Exchanges

If the lack of communication between the U.S. and Chinese militaries does not keep you up at night, well it should. The U.S. has a better relationship with Russia’s military than it does with China’s, but has more potential to cross paths with China’s because of the U.S.’ military presence in Asia. Without proper channels of communication between the two militaries, a small skirmish can easily become a major crisis, as President Obama knows from his first months in office when Chinese navy ships circled and threatened a U.S. navy vessel in the South China Sea.

Adding to the lack of communication is China’s broad interpretation of its “exclusive economic zone” (EEZ). A  country’s EEZ extends 200 miles from the coast and gives the country sovereign rights over economic activities in those waters (usually the country uses its economic zone to search for natural resources). By China’s broad definition, its sovereign rights in the EEZ expand outside of the economic realm, permitting it to interfere with other countries’ ships that enter its EEZ. The U.S., as well as most other countries, perceives the EEZ as providing solely economic sovereignty for the coastal state, allowing other countries’ ships free access. For the U.S., this also includes ships that are conducting military surveillance on the coastal state (for an excellent assessment of these different interpretations, see Margaret K. Lewis’ “An Analysis of State Responsibility for the Chinese-American Airplane Collision Incident”). Needless to say, these different interpretations only add to the tensions between the two militaries.

country’s EEZ extends 200 miles from the coast and gives the country sovereign rights over economic activities in those waters (usually the country uses its economic zone to search for natural resources). By China’s broad definition, its sovereign rights in the EEZ expand outside of the economic realm, permitting it to interfere with other countries’ ships that enter its EEZ. The U.S., as well as most other countries, perceives the EEZ as providing solely economic sovereignty for the coastal state, allowing other countries’ ships free access. For the U.S., this also includes ships that are conducting military surveillance on the coastal state (for an excellent assessment of these different interpretations, see Margaret K. Lewis’ “An Analysis of State Responsibility for the Chinese-American Airplane Collision Incident”). Needless to say, these different interpretations only add to the tensions between the two militaries.

In the U.S.-China Joint Statement issued last week, much needed progress was made on the military front, especially in terms of communication. High level exchanges between the U.S. and Chinese militaries will continue, with the Chief of the General Staff of the China’s People’s Liberation Army, General Chen Bingde, visiting the U.S. and both Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Michael Mullen making a trip to China.

In regards to differing definitions of the EEZ, the Joint Statement alludes to this issue, showing that the two sides likely discussed and acknowledged the problem (From the Joint Statement: “The United States and China agreed to handle through existing channels…maritime issues in keeping with norms of international law and on the basis of respecting each other’s jurisdictions and interests”). Granted they failed to reach a compromise, but this is not an issue that will be easily solved. Just discussing this sensitive topic is progress.

2. Both Public and Private Discussion of Human Rights

Interestingly, a press that largely ignored this issue prior to President Obama’s trip is making a big deal of his “silence” on human rights violations in China. Last I checked though, freedom of speech is usually regarded as one such right and President Obama discussed this issue rather bluntly and passionately at the Shanghai town hall. While it is debatable as to whether focusing on freedom of expression on the internet is sufficient to assist China with a development of a civil society and a rule of law, it is difficult to argue that President Obama did not publically bring up the subject of human rights.

Furthermore, in his letter written to China’s Southern Weekend newspaper, President Obama stressed the importance of a free press. True, this letter was not permitted to be circulated to a wider audience, but it portrays the President’s continued emphasis, both publically and privately on human rights.

The Joint Statement also discusses human rights in general and calls for the next official human rights dialogue between the U.S. and China to be held by the end of February 2010 in Washington, D.C. The Joint Statement also stressed the importance of rule of law in China and agreed to reconvene the U.S.-China Legal Experts Dialogue (see the Dui Hua Foundation website for further background). With the increasing push back by the Chinese government in the area of rule of law, especially as it pertains to civil rights and civil liberties, deepening cooperation is an important deliverable.

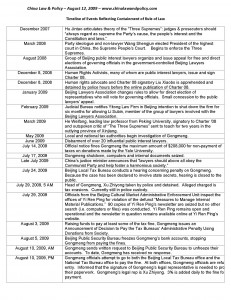

It is true that the Obama Administration has opted more for a strategy of quiet engagement on this issue. Whether the approach is effective remains to be seen. This past summer, the Administration was able to secure the release of public interest attorney Xu Zhiyong through behind the scenes pressure on the Chinese government. However, almost immediately after President Obama left China, the Beijing police apprehended and beat public interest lawyer Jiang Tianyong (pronounce Geeang Tian-young) as he was walking his 7 year old daughter to school. While Mr. Jiang has since been released, he is under very tight surveillance. Perhaps if President Obama had mentioned the plight and importance of public interest attorneys in China, the arrest of Mr. Jiang might not have happened. Or maybe it would have.

Either way, the U.S. press’ conclusion that President Obama “soft-peddled” human rights on his trip does not appear to ring true. Human rights was certainly discussed, both publically and privately, it just appears that perhaps China was not listening.

3. Clean Energy and Climate Change

As expected, the U.S. and China entered into a series of cooperative agreements pertaining to clean energy and climate change technology. While neither side agreed to emission targets, the level of detail provided for in the issued agreements was more than anticipated. Most interestingly, the U.S.’ Environmental Protection Agency and China’s National Development Reform Commission signed a memorandum of cooperation to help China develop its capacity to measure its greenhouse gas inventories. This is no small feat. China’s does not currently have the capacity to accurately measure its greenhouse gas emissions and thus, if it was to agree to emission targets, would be unable to provide verifiable data. China’s lack of capacity on this front has rightly been a sticking point for many in the U.S. Congress, preventing the passage of domestic climate change legislation that would be used to bind the U.S. internationally.

This memorandum of cooperation is the first step to enable China to agree to emission targets and for the rest of the world to believe them.

President Obama’s visit to China was certainly not overly exciting but it was far from the failure that the U.S. press has made it out to be. It also does not signify the U.S.’ decline as some alarmist media outlets have claimed. Instead, the visit was a series of tough negotiations between two global powers. Both had winning issues and losing ones. And in the end, President Obama likely walked out with a little more than expected. For me, that’s an accomplishment.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email