Obama, the Dalai Lama and Tibet – What’s all the Fuss?

President Obama welcomes the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader, to the White House today. With this visit come renewed fears that U.S.-China relations are in a downward spiral.

Obama’s Meeting with the Dalai Lama will Not Harm U.S.-China Relations

The U.S. press has been adamant that President Obama’s meeting with the Dalai Lama will strain U.S.-China relations. But this fear is misplaced. Similar to the inevitability of U.S. arms sales to Taiwan, the Chinese government knows that a meeting with the Dalai Lama is a done deal – a U.S. president, at some point during his term, will invite the Dalai Lama to the White House.

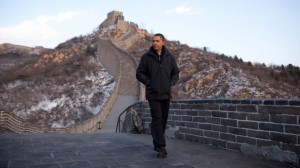

Since 1990, every U.S. president has met with the Dalai Lama. Obama’s meeting today is far from a surprise to Beijing; it’s what U.S. presidents do. The topic even came up during President Obama’s visit to Beijing in November. And the Obama Administration was fully aware that any contact with the Dalai Lama would elicit an angry response from Beijing. It always does.

These recent events – the decision to meet with the Dalai Lama and China’s vocal response – in no way reflect a change in policy; it’s not a reflection of China flexing its muscles nor is it a reflection of a more hard-line approach by the U.S. It’s merely just par for the course in U.S.-China relations; a rite of passage of sorts.

This isn’t to say that there has not been a change in the relationship. The U.S.’ vocal critique of China’s internet censorship and the increasingly belligerent tone regarding China’s currency could show a stronger stance toward China. Additionally, if China votes against sanctions against Iran or decides to abstain from Six-Party talks with North Korea, this could symbolize a China feeling stronger in the world. But the rhetoric surrounding the Dalai Lama’s visit in no way represents a changed policy.

Beijing is Actually Happy about Obama’s Meeting with the Dalai Lama

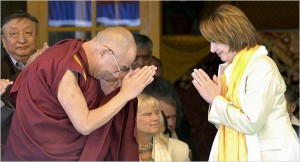

Well, “happy” might be a bit of a stretch, but Beijing is, at the very least, satisfied with the concessions that President Obama has already made. Beijing knows things could be much worse (for them at least). In 2007, President George W. Bush welcomed the Dalai Lama to the White House, and in a public ceremony, awarded him the Congressional Gold Medal. Never before had a U.S. president met the Dalai Lama in public; and to award him with one of the highest civilian awards, just added insult to China’s injury.

Needless to say, this enraged the Chinese government, and post 2007, Beijing went on a global rampage to end foreign governments’ meetings with the Dalai Lama. According to an interview with Tibetan scholar Robert J. Barnett, China has been largely successful with its strategy: “[l]ast year, only two national leaders met the Dalai Lama….compared to twenty-one in the previous four years.”

Comparatively, President Obama’s meeting tomorrow is much less confrontational than his predecessor’s. President Obama will meet the Dalai Lama in private, and while the meeting will be held in the West Wing of the White House (not in the private residence as President Bill Clinton did and what the Chinese government would prefer), it will not be held in the Oval Office. Instead, President Obama will meet the Dalai Lama in the less prestigious Map Room. While this seems inconsequential to the American audience, this distinction is of high significance to China and is likely sufficient to placate the country.

So Why all the Hoopla?

In an interview with NPR, China historian Jeffery Wasserstrom explained the problem succinctly – both countries use this meeting to play toward their domestic audiences. If the U.S. president did not meet with the Dalai Lama, he would receive censure from Congress, human rights groups, and the public at large. Last fall, prior to his trip to China, President Obama postponed a meeting with the Dalai Lama and received a lot of heat for it; the move was portrayed as a way to gain favor with China prior to his visit to Beijing.

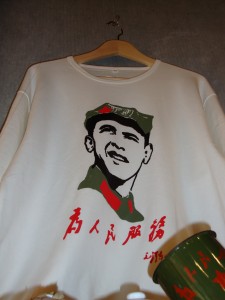

Similarly, the Chinese government must cater to its domestic audience; part of that catering is to use angry rhetoric

against any government leader who meets with the Dalai Lama. To its people, the Chinese government portrays the Dalai Lama as a separatist intent on splitting Tibet from China. Mix this with the Chinese government’s emphasis on nationalism, sovereignty and Tibet as an integral part of China, and you have a dangerous game. The Chinese government has created a self-fulfilling prophecy – by encouraging strong feelings of nationalism, the people then demand that the Chinese government act upon any perceived slights to this nationalism. In the case of Tibet, even though much of the people’s feelings are manufactured by the government, if the Chinese government does not respond with sharp attacks against anyone who meets with the Dalai Lama, then the people will begin to question its legitimacy.

The End Result for Tibet

So the dance continues. But the third wheel here is the Tibetan people. For the U.S. and China, this is a symbolic game to placate their respective domestic audiences; but for the Tibetans, this is about survival. With each new U.S. president and with each new meeting with the Dalai Lama, there is a hope that the situation in Tibet can be resolved.

The Dalai Lama has not been allowed to return to his homeland and minister to his people, and the with an influx of ethnically Han Chinese into Tibet and laws that limit the Tibetan’s religious practices, it is questionable if the religion, the culture, and the people will be able to survive. At the same time, negotiations between Beijing and envoys of the Dalai Lama have been at a standstill for over 15 years now, with the Tibetan side refusing to budge on its demand for greater autonomy, not just for the land mass of Tibet, but for all areas in China where there is a large population of Tibetans (this would be a little like Puerto Rico asking for greater autonomy for the island of Puerto Rico and also the South Bronx, Spanish Harlem and other areas of the U.S. with large Puerto Rican populations). The Dalai Lama’s envoys met with officials in Beijing last month, but again the talks proved fruitless.

For the past 20 years, the U.S. has relied on symbolic gestures in its dealings with Tibet and has done little to actually move the dialogue between the Dalai Lama’s representatives and Beijing forward (see Melyvn C. Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet and the Dalai Lama). There’s a lot of focus on the Dalai Lama’s visit to the White House, but there is never a discussion as to why. What does this do? Where does this get the Dalai Lama?

What’s at stake here is more than just a popularity contest and the time for symbolic gestures has long passed. Both China and the Dalai Lama are entrenched in their positions and neither is going to budge, but to move forward, a compromise is needed. And each side does want to move forward; the Dalai Lama wants to return to Tibet and provide for greater religious freedom for Tibetans, and the Chinese government doesn’t want to live with the constant threat of riots and protests in the region. But at this stage, a third-party, like the U.S., needs to step up to the plate to help negotiate a compromise – symbolic meetings won’t do the job. Without the role of a third-party, there will never be progress.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email