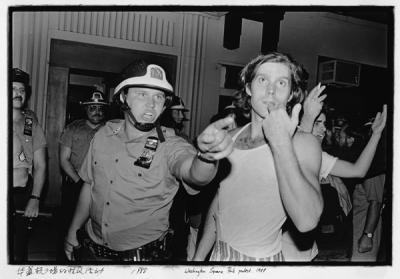

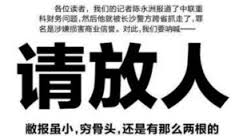

To Arrest or Not to Arrest – Prosecutors Have to Today to Determine Fate of Five Female Activists

On Thursday, the New York Times reported that the Beijing police requested that the local prosecutor formally arrest the five Chinese women detained for planning an anti-sexual harassment demonstration on Intentional Women’s Day (March 8). According to the detained women’s lawyers, the recommended charges are “organizing a crowd to disturb public order” (Article 291 of China’s Criminal Law), a charge different than the initial basis for detention: “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (Article 293(4) of China’s Criminal Law).

Since the inception of these detentions on March 6, 2015, little has been transparent, even to the lawyers for the women. In fact, according to the New York Times, the women’s lawyers were not even informed that a request for arrest had been made to the prosecutors on April 6, 2015. According to a phone interview with Liang Xiaojun, one of the detained women’s attorneys, the police’s April 6 request for arrest means that the prosecutors must decide by today if there is enough evidence for such an arrest. (see also Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”) Art. 89 requiring that the prosecutor’s office determine within 7 days whether to formally arrest the suspect). But like everything else that has been happening in this case, likely the detained’s lawyers will continue to be kept in the dark of today’s decision.

Two years ago the Chinese government heralded the passing of its amended

Criminal Procedure Law, which was intended to bring China more inline with the international community. Scholars and government officials praised the law for its greater protection of criminal suspects’ rights and improved access to defense lawyers early in the process. But the detention of these five women, exemplifies the continued weaknesses of the Criminal Procedure Law and its failure to protect suspects’ rights. Where it does offer some protections, what’s happened to these five women, demonstrate that Chinese police and prosecutors continue to skirt the law with impunity. This post will review some of the major issues with the detention of China’s five women activists.

The Police Have Not Issued Any Document with the Charges. Is That Legal?

No. In a phone interview with Liang Xiaobin, Wu Rongrong’s attorney, Mr. Liang informed China Law & Policy that the police have yet to issue any formal document regarding the detention or potential charges against his client. But Art. 123 of the Ministry of Public Security’s “Procedural Regulations on the Handling of Criminal Cases by Public Security Organs (revised 2012)” (“MPS Regulations” or “Regs”) which implements the CPL, a detention notice must be issued to the family of the detained within 24 hours of detention. That detention notice would list the charges being investigated. Presumably if such a notice was provided to Wu’s family, it would be transmitted to Liang. But Liang has yet to obtain any verification of any charges other than those verbally communicated to him.

The Police Did Not Inform the Five Women’s Lawyers that it Had Recommended Arrest. Is This Legal?

Yes, and this is where one of the major weaknesses in the new Criminal

Procedure Law and its implementing regulations is obvious. During the pre-arrest phase, even when a suspect has retained a lawyer, that lawyer has very little ability to access any of the police or prosecution documents. In fact, neither the CPL nor the MPS Regulations require that the police or prosecutor inform the lawyer of what is happening in the case. There is some information that has to be told to the detained’s family (that the suspect has been detained (CPL Art. 83 & MPS Reg Art. 123); that the suspect has been formally arrested (MPS Reg. 141)), but the police do not have to affirmatively inform the family that the police have recommended arrest to the prosecutor, even though there is a paper trail for all of this (see CPL Art. 85 & MPS Reg. Art. 133 both requiring a written formal request be made by the police to the prosecutor) Without this information, it becomes difficult to hold the prosecutor to the 7-day limit to decide whether to arrest (CPL Art. 89).

But no where in the CPL or the MPS Regulations does anyone have to inform the retained lawyers of anything. It is not until the prosecutor begins to investigate for indictment (审查起诉) do rights attach to the defense lawyer. When that occurs – and again, the law is unclear if anyone has to be affirmatively informed that such a review is occurring – can defense counsel access information from the state. At that point, the prosecutor’s office is required to share the case file (CPL Art. 38). But up until that point, keeping the defense attorney in the dark is completely legal.

Allegedly, the Women Were Denied Easy Access to their Lawyers & When Able to Meet, Conversations Were Recorded. Is this legal?

No. The amended CPL was specifically modified to rid the Chinese criminal justice system of these patently unfair practices. But according emails issued by Yirenping, a Chinese-NGO that many of the women are affiliated with, many of the lawyers’ requests to meet with their clients have been ignored. The few times the lawyers have been able to meet with their clients, according to Yirenping, the conversations have been recorded.

Article 37 of the CPL clearly requires that detention centers promptly schedule meetings between lawyers and their clients when the suspected charges do not include national security; such meetings must be scheduled no later than 48 hours after the request. The MPS Regulations reiterate that right (MPS Regs. Art. 48). Further, Article 37 of the CPL plainly states that conversations between the lawyer and his or her client are not to be monitored (see also MPS Reg. Art. 52).

Is the Limit for Detention 30 days?

This is unclear. Although the lawyers for the five women have stated that detention can only be for 30 days before moving to the next stage of the case (here, the police formally requesting that the prosecutors arrest the women) and the police have conveniently stated that it did in fact move the case forward on April 6 (approximately 30 days after the initial detentions), it is unclear whether there is in fact a 30 day limit to detention. Article 89 of the CPL states that detention, without a request for arrest, is generally limited to three days. But the police can unilaterally extended that limit for an additional four days (making for a total of seven days).

But for suspects being investigated for “multiple crimes” (like the women here) or “crimes across multiple regions” (again, like the women here), the police may add an extra 30 days to the detention (CPL Art. 89). In both the English and Chinese, it is unclear if that 30 days is added on top of the seven that was permissible or if 30 days is the outer limit of detention before request for arrest. Although both the attorneys in this case and the police seem to maintain that 30 days is the limit, the law is not clear. But at the most, 37 days is limit for detention.

Was it legal to bring Wu Rongrong and Zheng Churan to Beijing for detention?

Yes. Of the five women detained, two – Wu Rongrong, director of the Hangzhou-based Weizhiming Women’s Center and Zheng Churan, staff member at Yirenping Guanzhou, live outside of Beijing. Both were planning their International Women’s Day demonstrations in their respective cities and both were initially detained by the public security officials in each city. But both were eventually transferred to Beijing’s Haidian Detention Center where the other three women, Wang Man, Wei Tingting and Li Tingting, all residents of Beijing, were being held.

Both the CPL and the MPS Regulations permit the easy movement of suspects between cities, counties and provinces when appropriate. Although the default presumption is that jurisdiction of a criminal case is where the crime was committed (see CPL Art. 24; MPS Regs Art. 15), both the Criminal Procedure Law and the MPS Regulations contemplate instances where that might not be the case, especially when there are multiple crimes and/or multiple defendants.

In fact, an entire Chapter of the MPS Regulations – entitled Cooperation in Case-

Handling (Chapter 11, encompassing Articles 335-344) – specifically deals with these situations. Unlike in the United States, where extradition from one state to another is a formal affair, here the transfer of a criminal suspect is more informal (see MPS Regs Art. 335 requiring local public security bureaus to cooperate with a request to detain a suspect & Art. 336 requiring only a “letter of cooperation” to obtain the locality’s cooperation). Presumably the Beijing PSB provided such a letter to the Hangzhou and Guangzhou PSBs in order to detain and eventually transfer Wu Rongrong and Zheng Churan to Beijing.

Will the Women Be Arrested?

Increasingly likely. The fact that the police have changed the charges and have added more incidents to the charge, such as the women’s street performance demonstration against domestic violence where they dressed up in wedding dresses with fake blood and their “occupy men’s toilets” day to demonstration the insufficiency of women’s toilets in public places, provides for more evidence for arrest. Further, adding extra incidents and making this multi-crime case, arrest and continued detention is all but certain. According to Article 139(1) of the People’s Procuratorate’s Criminal Procedural Regulation (revised 2012), the prosecutor’s implementing regulations of the CPL, arrest is necessary when the criminal suspect may commit a new crime. What provides evidence that the suspect might commit another crime if not detained? The fact that “the suspect has committed multiple crimes, changed locations in committing multiple crimes, committed related crimes…”

Within 24 hours of the police’s decision to arrest, the police must inform the family (MPS Reg. Art. 141). Under Chinese law, the world should know by Tuesday if an arrest was made. But that’s assuming that anyone actually follows the law.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email