Jiang Tianyong

For the Chinese state, human rights lawyer Jiang Tianyong (pronounced Gee-ang Tee-an Young) never seems to learn his lesson. In 2009, after taking on a slew of politically sensitive cases such as representing Falun Gong practitioners and ethnic Tibetans prosecuted following the 2008 Tibet riots, the Beijing Bureau of Justice declined to renew Jiang’s lawyers license.

But lack of a law license did not stop Jiang from continuing to advocate for some of China’s most vulnerable. Instead, Jiang played an active role in ensuring that blind activist Chen Guangcheng‘s cruel house arrest remained in the public eye. Again the Chinese state came for Jiang. In February 2011, after meeting with fellow advocates to discuss Chen Guangcheng’s case, Jiang was abducted by local police, beaten, psychologically tortured and held incommunicado for two months. (For Jiang’s own description of his two month ordeal, click here). Jiang was released, but only after he promised to give up his advocacy work, stop associating with his current friends, cut off ties with foreigners and refrain from making comments on social media disparaging the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Jiang, on the left, with other human rights attorneys and advocates, protesting in Heilongjiang

But even in light of these guarantees, Jiang’s advocacy did not cease. Nor did the Chinese state’s reprisals, which became increasingly violent. In May 2012, Jiang attempted to visit Chen Guangcheng in a Beijing hospital. After Jiang was denied entry, state security officers took him away, beat him and then placed him under surveillance. In 2013, when Jiang exposed Sichuan province’s largest “black jail,” a secret and unlawful detention center, he was again beaten by local police. When, in 2014, Jiang went to Heilongjiang province to protest the detention of Falun Gong practitioners in a “legal education base,” Jiang was administratively detained for 15 days and subject to various beatings while in police custody.

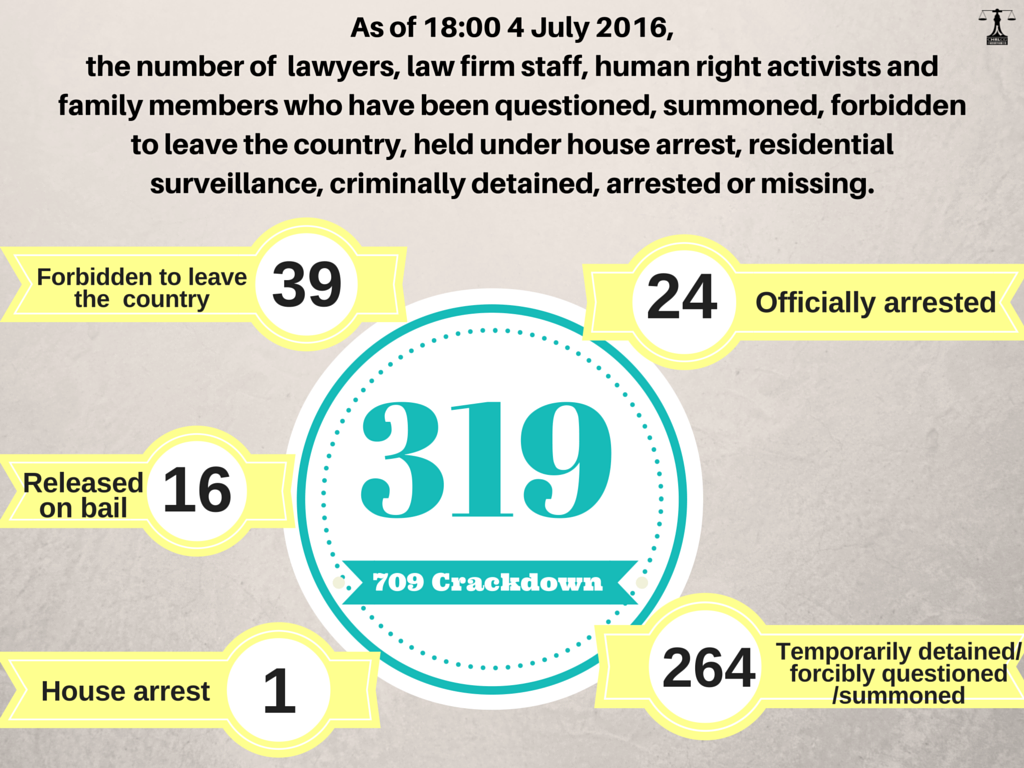

Not surprisingly, Jiang, who has yet to give up his advocacy, is back on the Chinese government’s radar, this time with much more serious charges that could land this civil rights attorney in prison for life. But there is one thing that should make this time different from Jiang’s prior detentions: the implementation of China’s new Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”), amended in 2012. When these amendments passed, they were herald as more protective of criminal suspects’ rights, much needed in a system with a 99.9% conviction rate. In October 2016, the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”), Supreme People’s Procuratorate (“SPP”), and the Ministry of Public Security (“MPS”) doubled down on the 2012 amendments, issuing a joint opinion, reaffirming each agency’s commitment to a more fair criminal justice system.

But as Jiang’s case highlights, these are just paper promises. For Jiang, some of the provisions of the CPL are outright ignored. But more dangerously, the Chinese police have placed Jiang under “residential surveillance at a designated location,” a form of detention that was added to the CPL with the 2012 amendment. In the case of Jiang, this amendment is being used to keep him away from his lawyers and, with his precise whereabouts unknown to the outside world, in a situation where torture while in custody is highly likely. So much for better protecting criminal suspects’ rights.

But as Jiang’s case highlights, these are just paper promises. For Jiang, some of the provisions of the CPL are outright ignored. But more dangerously, the Chinese police have placed Jiang under “residential surveillance at a designated location,” a form of detention that was added to the CPL with the 2012 amendment. In the case of Jiang, this amendment is being used to keep him away from his lawyers and, with his precise whereabouts unknown to the outside world, in a situation where torture while in custody is highly likely. So much for better protecting criminal suspects’ rights.

Why Is Jiang Under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Place?

On November 21, 2016, Jiang went missing. According to the Legal Daily, Jiang was picked up by the Changsha police after using someone else’s identity card to purchase a train ticket home to Beijing. After being taken into custody, Jiang is now suspected of harboring state secrets, a crime that carries a three to seven year prison sentence depending how serious (Crim. Law Art. 282) and of providing those state secrets abroad, a crime that results in a sentence anywhere between five years to life depending on the severity (Crim. Law Art. 111).

However, according to an advocate close to the investigation, the police notice eventually issued to Jiang’s family also lists suspicion of inciting subversion of state power, a national security crime that the Chinese government has increasingly used to silence its civil rights lawyers. That charge can carry a sentence of anywhere between three years to life (Crim. Law Art. 105), and where inciting subversion involves foreign entities, the punishment shall be heavier (Crim. Law Art. 106).

Jiang Tianyong’s wife, Jin Bianling, calling on the Chinese government to inform her of her husband’s whereabouts. Photo courtesy of Hong Kong Free Press

For close to a month, Jiang’s whereabouts were unknown; unknown to his lawyers and to his family. And while this might seem illegal, China’s amended Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”) forgoes many of the protections intended to make the system more fair when the crime of endangering national security is potentially involved. When a suspect is taken into custody, Article 83 of the CPL requires that the police inform the suspect’s family within 24 hours except for those crimes that endanger national security or involve terrorism. Here, Jiang is suspected of subverting state power and passing state secrets abroad, two crimes that certainly endanger national security. And as a result, the police did not inform Jiang’s family that he had been taken into custody.

In what is increasingly necessary when a civil rights lawyer lands in the exclusive control of the police and his whereabouts are unknown, Jiang’s family and friends resorted to the one tool they had left: pressuring the foreign press to repot that Jiang had gone missing. With the story of Jiang’s abduction splashed across the international press, on December 16, 2016, the Chinese government, through the government-controlled Legal Daily newspaper informed the world that Jiang not only had been taken into custody but that he was placed in “residential surveillance in a designated place.”

Residential Surveillance in a Designated Place – likely not here.

One of the major amendments to the CPL included what China terms a “compulsory measure” but in reality is a new form of detention: “residential surveillance” (Articles 72 through 77 of the amended CPL). Residential surveillance might sound like a more mellow form of detention but when applied, it provides carte blanche for police to interrogate – and usually torture – a suspect without any interference from the outside world.

For any residential surveillance that occurs outside of the suspect’s hometown, or if the suspect is being investigated for crimes of “endangering state security,” “terrorism” or “serious crimes of bribery,” residential surveillance does not occur at one’s home. (CPL, Art. 73) Instead, it occurs at an undisclosed location and while the family is required to be informed that their relative is under residential surveillance at a designated place (CPL, Art. 73), the family is not necessarily informed as to the precise location of the place.

And this is why Jiang shouldn’t be expecting any care packages in the near future from his family; they have no idea where he is. In fact, according to a source close to the investigation, Jiang’s family first learned about his residential surveillance through the Legal Daily article on December 16, 15 days after he was placed in that form of detention. True that the amended CPL does a great job at severely circumscribing suspects rights once they are under residential surveillance, but the one thing that the Chinese government still gives these suspects is reuiring the police to provide a written notice to the suspect’s family within 24 hours of placing the suspect under residential surveillance, regardless of the type of crime involved, national security or not. (CPL, Art. 73; see also Ministry of Public Security Implementing Regulations of the CPL Art. 109) But here, according to an advocate close to Jiang’s case, Jiang’s family was not provided official notification until December 23, 2016, 22 days later.

And this is why Jiang shouldn’t be expecting any care packages in the near future from his family; they have no idea where he is. In fact, according to a source close to the investigation, Jiang’s family first learned about his residential surveillance through the Legal Daily article on December 16, 15 days after he was placed in that form of detention. True that the amended CPL does a great job at severely circumscribing suspects rights once they are under residential surveillance, but the one thing that the Chinese government still gives these suspects is reuiring the police to provide a written notice to the suspect’s family within 24 hours of placing the suspect under residential surveillance, regardless of the type of crime involved, national security or not. (CPL, Art. 73; see also Ministry of Public Security Implementing Regulations of the CPL Art. 109) But here, according to an advocate close to Jiang’s case, Jiang’s family was not provided official notification until December 23, 2016, 22 days later.

Under the residential surveillance provisions of the amended CPL, the police are given so much power over the suspect, power that is largely illegal in other forms of detention and for other crimes. But even with this power, the police still feel the need to violate the clear language of CPL Article 73 and withhold notice to Jiang’s family.

Jiang Can Be Held for Up To Six Months and Without Access to a Lawyer

Empty chairs at empty tables – No lawyer for Jiang anytime soon

Jiang should also not be expecting any visits from a lawyer for the six months that residential surveillance at a designated place is permitted. (CPL, Art. 77) And that’s another way that, by slapping a national security charge on a suspect, the Chinese government is able to circumscribe rights otherwise enshrined in the amended Criminal Procedure Law.

Because “residential surveillance in a designated place” usually presupposes a possible state security, terrorist, or serious bribery charge, the requirement that a meeting with the lawyer take place within 48 hours (CPL, Art. 37) is suspended for those possible charges. (CPL, Art. 37). Instead, any meeting must be approved by the police. (CPL, Art. 37). Which fits with the rules that the suspect must follow when in residential surveillance: only with permission of the public security agency can the suspect meet or correspond with someone else. (CPL, Art.75(2)). That permission must be granted unless the investigation would be obstructed or national secrets may be leaked (Ministry of Public Security Implementing Regulations of the CPL Art. 49)

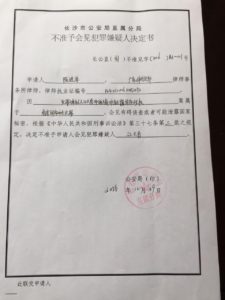

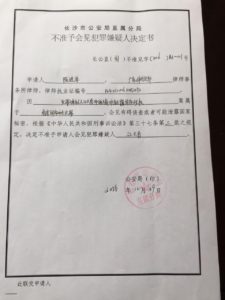

Changsha police notice informing Jiang Tianyong’s lawyer that he cannot meet with Jiang due to crimes endangering national security (click for bigger image)

Although the regulations strongly favor meeting with a lawyer, in practice, civil rights attorneys held on charges that involve endangering national security are rarely given approval to meet their attorney. Jiang is no exception. According to an advocate with close ties to Jiang’s case, on December 27, 2016, Jiang’s lawyer requested permission to meet with his client. On December 29, 2016, Changsha police denied this request, stating that “Jiang Tianyong was accused of crimes of endangering state security, and a meeting with lawyers would obstruct the investigation or possibly divulge state secrets.”

Codifying Illegality?

Jiang’s case makes clear that the 2012 CPL amendments have done little to curb the power of the police and that the Chinese government’s recent pronouncements that it needs to do better to protect suspects’ rights, is nothing more than window dressing. As long as the police unilaterally, and without due process, decide to investigate the suspect for crimes involving national security, all rights are essentially lost: the suspect can be held incommunicado for up to six months without access to a lawyer. That kind of situation – with no one watching – all but guarantees torture and abuse. Ironically, it is potential charges of endangering national security where these protections are needed most.

But, starting with the 2015 crackdown on lawyers and now continuing with Jiang Tianyong, the Chinese government has demonstrated that it will use the label of “endangering national security” to forgo the rights that it says it is committed to providing criminal suspects. In late 2015 and early 2016, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate issued two sets of rules ostensibly to curb the police’s abuse of residential surveillance in a designated location. But, as others have noted, the new rules seem to be designed more to ensure that everything looks good on paper than to guarantee criminal suspect’s rights and access to due process. The case of Jiang Tianyong appears to prove that even those new regulations have had no effect.

But, starting with the 2015 crackdown on lawyers and now continuing with Jiang Tianyong, the Chinese government has demonstrated that it will use the label of “endangering national security” to forgo the rights that it says it is committed to providing criminal suspects. In late 2015 and early 2016, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate issued two sets of rules ostensibly to curb the police’s abuse of residential surveillance in a designated location. But, as others have noted, the new rules seem to be designed more to ensure that everything looks good on paper than to guarantee criminal suspect’s rights and access to due process. The case of Jiang Tianyong appears to prove that even those new regulations have had no effect.

As the rest of the world marks the seventh annual Day of the Endangered Lawyer next Tuesday, Jiang Tianyong, one of China’s great civil rights attorneys, languishes in an unknown place, likely subject to constant interrogation and torture, and without any access to a lawyer. His rights deprived all because the Chinese police are able to claim that it is investigating him for endangering national security. But the only thing that is being endangered by making a mockery of the protections of the amended Criminal Procedure Law is the actual rule of law.

*****************************************************************************

Thank you to China Law Translate for providing free of charge most of the translations of China’s laws used in this article.

To call China’s human rights lawyers “battered” is an understatement. These lawyers are victims of the Chinese government’s deliberate and brutal pursuit to render them extinct. And that is why the nomination of Chinese human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang for the Dutch government’s Human Rights Tulip award is so significant and why readers should vote for him (public voting is open here until September 6, 2017).

To call China’s human rights lawyers “battered” is an understatement. These lawyers are victims of the Chinese government’s deliberate and brutal pursuit to render them extinct. And that is why the nomination of Chinese human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang for the Dutch government’s Human Rights Tulip award is so significant and why readers should vote for him (public voting is open here until September 6, 2017).

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

But, starting with the

But, starting with the

While alarming, on some level Shi Fulong is lucky that the op-ed does not cite more although he is certainly bordering on the danger zone. Likely in an attempt to contain China’s civil rights lawyers, in the past couple of years, the Chinese’s government has sought to penalize and contain the zealous advocacy that is required of lawyers, especially civil rights lawyers. In the Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) recent

While alarming, on some level Shi Fulong is lucky that the op-ed does not cite more although he is certainly bordering on the danger zone. Likely in an attempt to contain China’s civil rights lawyers, in the past couple of years, the Chinese’s government has sought to penalize and contain the zealous advocacy that is required of lawyers, especially civil rights lawyers. In the Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) recent

It’s not only the South China Sea that is witnessing China’s differing interpretation of international law and its commitments under various treaties. With its

It’s not only the South China Sea that is witnessing China’s differing interpretation of international law and its commitments under various treaties. With its  In

In