When Journalism Is not Journalism: The Grayzone’s Faulty Analysis of What is Happening in Xinjiang

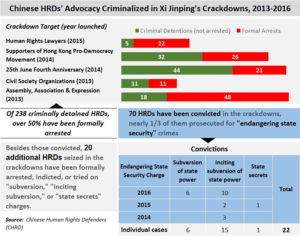

When I started seeing the Grayzone, a website that describes itself as “dedicated to original investigative journalism,” touted in various Chinese media reports (see here and here) for a study that allegedly debunked the estimate of one million Uighurs detained in internment camps in Xinjiang, I felt like I had to read it. But to call the Grayzone piece an analysis – or even objective journalism – would be a serious overstatement. Instead, Ajit Singh and Max Blumenthal, the authors of “China detaining millions of Uyghurs? Serious problems with claims by US-backed NGO and far-right researcher ‘led by God’ against Beijing,” largely dedicate their piece to the character assassination of the two organizations/people who first estimated the one million figure: the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) and Adrian Zenz, a social scientist at the European School of Culture & Theology and now a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

When I started seeing the Grayzone, a website that describes itself as “dedicated to original investigative journalism,” touted in various Chinese media reports (see here and here) for a study that allegedly debunked the estimate of one million Uighurs detained in internment camps in Xinjiang, I felt like I had to read it. But to call the Grayzone piece an analysis – or even objective journalism – would be a serious overstatement. Instead, Ajit Singh and Max Blumenthal, the authors of “China detaining millions of Uyghurs? Serious problems with claims by US-backed NGO and far-right researcher ‘led by God’ against Beijing,” largely dedicate their piece to the character assassination of the two organizations/people who first estimated the one million figure: the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) and Adrian Zenz, a social scientist at the European School of Culture & Theology and now a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

By focusing almost exclusively on ad hominem attacks, Singh and Blumenthal conveniently ignore that subsequent data sources have confirmed a one million number as credible. And most absurdly, after portraying the CHRD and Zenz’s admissions that their numbers are merely estimates as a fatal flaw, Singh and Blumenthal completely fail to acknowledge why we can only estimate the number detained. The keeper of the exact numbers – the Chinese government – refuses to publish any numbers let alone permit international monitors to enter Xinjiang and conduct their own, independent, on-the-ground analysis.

But regardless of the uselessness of the Grayzone article, it is good to periodically question our assumptions and re-review where exactly the the one million number comes from. About a year ago, Jessica Batke, a senior editor at Asia Society’s ChinaFile and a former intelligence analyst at the U.S. Department of State, did just that, meticulously explaining why the one million estimate is likely not off the mark. This post largely summarizes Batke’s piece in the context of the Grayzone article.

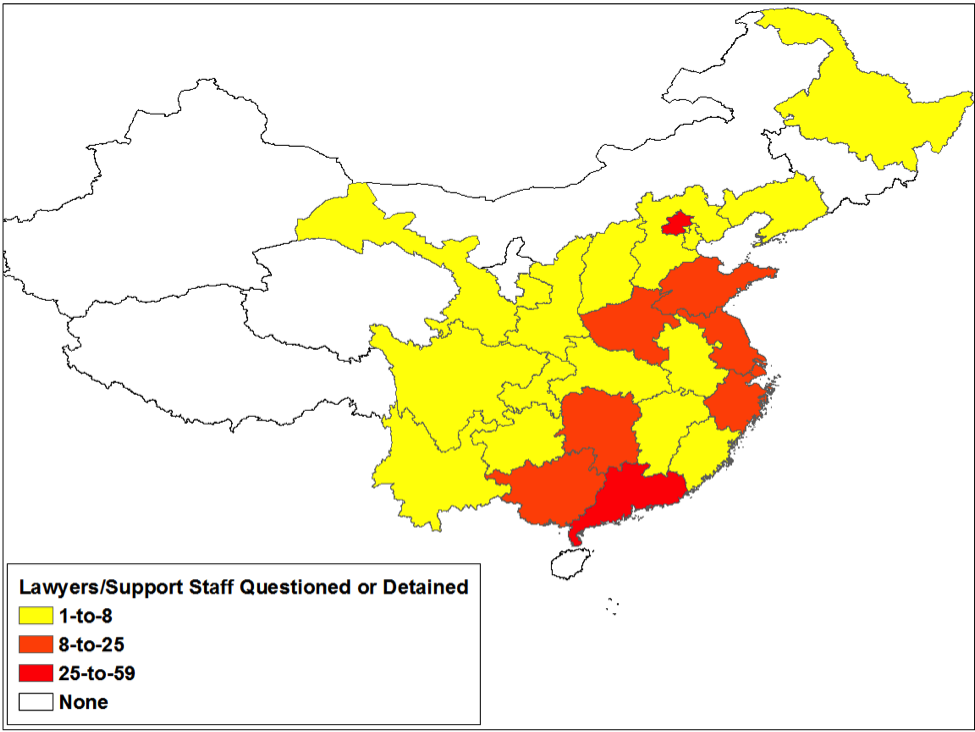

Singh and Blumethal begin their piece by questioning the CHRD study which was based upon interviews with eight ethnic Uighurs in Xinjiang. For Singh and Blumethal, drawing a conclusion of one million detained from just talking to eight people is preposterous. But the two choose to ignore the reasons why CHRD extrapolated one million detainees from its eight interviews. As Batke points out in her analysis, each of these eight Uighurs were from a different village in southern Xinjiang. Each person gave their estimate of the number of people who have gone missing in their village. Based upon that number, CHRD formulated a detention rate for each village which ranged between 8% and 20%. From those rates, CHRD chose a rather conservative estimate of a 10% Uighur detention rate province-wide, or, given that there are approximately 10 million Uighurs in Xinjiang, a one million detention number.

Certainly there are things to question on CHRD’s numbers: how did each of these eight people know the number of people missing? Are they interned or did they just move? But Singh and Blumenthal do not ask these questions. Instead, for them, the death knell for the reliability of the CHRD estimate is the fact that CHRD receives funding from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). But they never explain why this link matters or provide any evidence that this funding somehow undermines the reliability of CHRD’s estimate.

Similarly, Singh and Blumenthal’s review of Adrian Zenz’s study is more focused on his religious and political viewpoints, and his current source of funding, rather than on the data itself. In the little attention the two give to Zenz’s data, they completely mischaracterize it. Singh and Blumenthal state that Zenz’s one million estimate was based upon numbers reported by Istiqlal TV, a Uigher television station based in Turkey that often features interviews with suspected terrorists, which Singh and Blumethal believe reflect Istiqlal’s inherent unreliability. But they conveniently leave out the fact that it was a Chinese public security official that leaked this data to Istiqlal TV, a fact later reported in Newsweek Japan. Batke also noted this fact in her careful analysis of Zenz’s one million estimate, highlighting that the Chinese-leaked data listed around 892,000 individuals in 68 different counties in Xinjiang as detained. However, as Zenz pointed out, the data was missing key population centers. But instead of simply assuming that the same detention rate applies to the missing population centers, a method that would produce much more than one million detained, Zenz did a deep dive on the missing population centers, taking into account important difference, and according to Batke, comes up with a conservative – and plausible – estimate of one million detained.

Batke also highlights corroborating evidence: the satellite images and Chinese government documents that also point to an equally large number of Uighurs being detained. In October 2018, the BBC had experts review satellite images of the camps. That group of experts concluded that 44 of the camps had a high or very high likelihood of being security facilities and a separate team architects determined that in examining one of these facilities, it could hold anywhere from 11,000 people, if each inmate has his or her own room, to 130,000 people, assuming these are dormitories. Camp survivors have stated that they lived in cells with as many as 40 people. Batke noted that if we took the higher number of people detained – which seems to be credible given survivors’ accounts – there would only need to be 10 similarly-sized camps to get to the one million mark. Finally, as Batke points out, the Chinese government’s own documents – both its procurement documents and budget and spending reports –suggest that a very large number of people are being detained.

The one million estimate as the number of Uighurs detained is Xinjiang is not coming out of thin air. Four different sources – CHRD, Zenz, satellite images, government documents – all come to the same conclusion. Media outlets like ChinaFile and Quartz have also re-reviewed the data and found the one million estimate credible. These outlets actively engage the data, unlike But Singh and Blumenthal whose focus is more character assassination. Ultimately the only purpose that Singh and Blumenthal’s article serves is as a perfect example of the logical fallacy of argumentum ad hominem.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email