Originally posted on the Huffington Post

Just before dawn on July 29, 2009, the Beijing police apprehended leading Chinese public interest lawyer, Xu Zhiyong, allegedly to question him about possible tax evasion. He has not been heard from since. In an increasingly conservative political environment in China, Mr. Xu’s detention is far from an anomaly. Many speculate that the Chinese government’s recent crackdown on public interest lawyers is merely a part of the preparations for the 60th

Xu Zhiyong; Photo by Shizhao

Anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China this fall. But in looking beneath the surface of the government’s recent actions, a different narrative emerges.

The apprehension of Mr. Xu, the forced closure of his legal assistance organization, Gongmeng (in English the Open Constitution Initiative), the investigation of Yi Ren Ping, a non-profit law center that assists AIDS and hepatitis patients with anti-discrimination actions, the recent disbarment of over 20 public interest lawyers, the professional “exile” of a leading legal scholar and outspoken critic to a remote region of China, all of these actions paint the picture of a government that has become increasingly more alarmed by a more vocal and organized group of lawyers. The government, and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) which ultimately controls all governmental bodies, has begun to view the development of these non-profit lawyers and legal reform as a threat to its authority and to the one-party rule of the CCP. Recent governmental assaults on the public interest law field are not just a one-off affair. Rather, they show a CCP not looking to embrace the “rule of law,” but instead seeking to contain it.

Development of Rule of Law in China from the US & Chinese Perspectives

Both China and the U.S. agree that greater rule of law in China is needed and can benefit China. Virtually every conference between the two nations mentions the need for rule of law development. But what is never articulated is what each means by “rule of law.” Many Western scholars claim that rule of law is value-neutral; it is merely a system where laws are enforced in a transparent manner by an independent judiciary and that rule of law can exist regardless of the political system of the country.

And while this is likely true, the U.S. government still largely views rule of law within the rubric of democracy; as the rule of law develops so does democracy and greater protection for human rights. Of the $27 million the government appropriated to rule of law projects in China in 2008, $15 million were administered by the Department of State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor and another $2 million was designated for non-State Department rule of law projects (see CSR report, p. 2).

China, however, takes a different perspective. While seeing the benefits of rule of law in terms of economic development, international acceptance and respect, and the ability for the central government to have greater control over the provinces, China has largely limited rule of law to the economic sphere and at times, a few other select areas. If a case involves a politically sensitive issue, involves an organized group of plaintiffs, or could unmask government malfeasance, the government will either not allow a case to proceed or will determine the ultimate outcome.

Even with this limited development toward legal reform, many U.S. policymakers believe that rule of law will continue to spread and permeate lawyers’, judges’ and society’s consciousness. This Trojan horse strategy assumes that legal reform in the economic sphere will inevitably spread to all areas of the law and to Chinese civil society. Government will be held more accountable to the people, laws will be administered transparently and all rights, political, economic and social, will be able to be vindicated. But proponents of this theory offer little to no evidence as to why. Why is this inevitable? Why can’t China succeed in limiting legal reform to the economic sphere? Why can’t rule of law be contained?

In other words, what if China is the black swan in the whole rule of law theory?

Emergence of a More Conservative Legal Ideology in China

Theory of the Three Supremes

The detention of Xu Zhiyong comes amid an increasing conservative political environment in China, at least in terms of legal reform. In December 2007, President Hu Jintao attempted to reassert the importance of the CCP in legal interpretation and reform by announcing his theory of “The Three Supremes:” judges and prosecutors should “always regard as supreme the Party’s cause, the people’s interest, and the Constitution and laws.” Although initially unclear if the Three Supremes were listed in hierarchical order, a recent announcement in July 2009 by a justice minister confirmed the hierarchical nature of the Three Supremes and the preeminence of the CCP when he called upon lawyers to “above all obey the Communist Party and help foster a harmonious society.”

Wang Shengjun, President of the Supreme People's Court

The Three Supremes is not just rhetoric. In March 2008, the National People’s Congress named Wang Shengjun, a Party insider without any legal training, as head of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), replacing reform-minded and trained lawyer Xiao Yang. Upon taking his position Wang has worked ardently to have the courts conform to the Three Supremes.

A More Organized Public Interest Law Movement

While the government expounds the Three Supremes and imposes this conservative ideology on the legal system, public interest lawyers have become increasingly organized and vocal. In August 2008, a group of 35 public interest lawyers in Beijing issued an internet appeal that requested that the government-controlled Beijing Lawyers’ Association (BLA) to conduct free and direct elections of governing officials of the BLA. In December 2008, human rights activists, many of whom are lawyers, signed Charter 08, a petition to the Chinese government calling for greater human rights, the end of one-party rule and an independent legal system. In addition, many of the non-profit lawyers, including Xu Zhiyong, have represented plaintiffs in politically sensitive cases, including cases pertaining to the Sichuan earthquake and the melamine milk scandal. Last year, Xu’s organization issued a report blaming Chinese policies in Tibet for the 2008 uprising in that region.

China’s Recent Response

Under the doctrine of the Three Supremes, China has not responded kindly to these public interest lawyers. Although the BLA slightly altered its voting rules by allowing for the direct election of representatives who then in-turn elected the governing officials, in February 2009, the local Judicial Bureau sought its revenge. After withholding a license from Li Subin, one of the advocates of the new voting procedures at the BLA, the Bureau issued an order for Yitong Law Firm, which employed Li, to shut down for six months for permitting a non-licensed attorney to practice law.

Liu Xiaobo, a leading human rights activist in China and signatory to Charter 08 was detained by police just hours before the publication of Charter 08. He remains in police custody. He Weifang, a well-known law scholar at the prestigious Peking University has been sent into professional exile and now teaches law in China’s most western region, Xinjiang.

Xu Zhiyong has faced a similar fate. In May 2009, tax authorities began to investigate Xu’s non-profit legal center, Gongmeng. On July 14, the Beijing office of the National Tax Bureau and the Beijing Local Tax Bureau each issued a notice to Gongmeng for non-payment of taxes on funds donated by Yale University and levied the maximum penalty of five-times the amount owed, or $208,000. On July 17, twenty officials from the Beijing Office of Civil Affairs barged into the Gongmeng offices, confiscating all materials including computers, case files, and furniture, and shut down Gongmeng. On July 29, Xu was apprehended by police for suspicion of tax evasion; he remains in custody.

In a Kafkaesque turn of events, on August 5, after raising at least some funds to pay its fine, the Beijing Public Security Bureau froze all of Gongmeng’s accounts. On August 10, in an attempt to discuss this matter with tax officials at the Beijing Local Tax Bureau and the National Tax Bureau, Gongmeng officials were escorted out. Authorities have informed Gongmeng that their recently filed paperwork is invalid because it does not contain the signature of Gongmeng’s legal representative, Xu Zhiyong. As this back-and-forth continues, Xu Zhiyong remains in police custody and the fine of $208,000 accrues daily compounded interest of 3%.

Also on July 29, officials from Beijing Cultural Market Administrative Enforcement Unit inspected the offices of Yi Ren

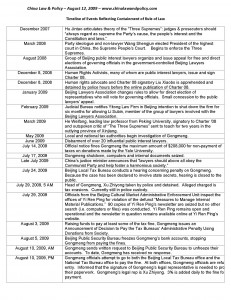

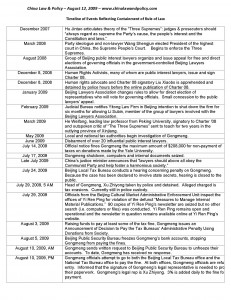

Click on image to open a PDF version of the Timeline of Events

Ping, a non-profit organization that files anti-discrimination lawsuits on behalf of people AIDS or hepatitis. Claiming that their search was being conducted under the Measures to Manage Internal Material Publications, a law that was repealed in 2001, the officials seized 90 copies of Yi Ren Ping’s newsletter.

China’s Containment of Rule of Law

The Chinese Communist Party is unified by one principle – to remain in power. Any organized effort, even if within the confines of the law, will be viewed as a threat to the CCP’s authority. In recent months, Chinese public interest lawyers have been effectively organizing themselves, especially through the internet, to challenge the current system. However, these lawyers are far from what the rest of the world would deem radical. They are merely using the laws passed by the National People’s Congress to protect people, especially those in disadvantaged groups like rural parents in Sichuan or people with AIDS. They are not looking to overturn underlying constitutional principles; they just want to enforce the law as written.

Even though these lawyers work within the system to improve Chinese society in a way that the law permits, as soon as they amass sufficient numbers, in the minds of the CCP, they are no longer operating within the legal system, but within the political one. In these situations, the CCP will abandon the legal system in favor of the political one.

But this is not to say that rule of law has not taken hold in China. Today, foreign corporations usually receive a fair hearing before arbitration commissions and the majority of cases handled by the courts are ordinary cases that involve little to no Party interference. There has been a marked increase in the professionalism of many judges and lawyers, and there is a sincere effort by many in the profession to develop greater rule of law.

However, those few cases that involve large groups of people or involve issues sensitive to the CCP, often do not receive the same transparent and independent judgment. In these situations, the outcome is ultimately determined by the CCP.

Thus far, China has been successful at confining rule of law development to non-political cases. The actions that have been taken against public interest lawyers in the past two years show China’s commitment to maintaining this separation. The government’s harassment and detention of public interest lawyers is intended to have a chilling effect on the profession. The low numbers of lawyers who seek a career in the public interest can be seen as a reflection of this impact.

But can China succeed in containing rule of law to certain areas? Many look to Taiwan and South Korea as an example of the inevitability of legal reform and democracy in an East Asian society. Both were under authoritarian regimes but eventually developed vibrant legal systems. However, China is in a very different place. Taiwan and South Korea were still dependent on the U.S. for trade and for military protection, and thus heavily influenced by the U.S. China, on the other hand, has become an economic and military powerhouse, beholden to few other nations. One of those countries is, of course, the United States, but China has gained significant leverage in this bilateral relationship by stocking up over $700 billion in US treasury bonds. All the while, it has been able to develop its economy while limiting legal development in the political and human rights spheres. Its continued rise only solidifies the need for this separation in the minds of the CCP leadership.

China’s future remains uncertain and only time will tell if rule of law does in fact permeate other areas of Chinese society. However, at this juncture, where China has become an important global power, it is important for U.S. policymakers to re-evaluate their assumptions of the rule of law landscape in China; and to ask themselves, what if China is successful in containing rule of law to certain segments? Can the U.S. live with that reality? Will it have a choice?

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email