Book Review – Green Island: A Novel

Tomorrow marks the 74th anniversary of the 228 (two-two-eight) Incident. Never heard of it? I hadn’t either until a couple of years ago. But the 228 Incident marks the start of a violent, dark period of Taiwan history: the White Terror. Starting on February 28, 1947 and for the next 40 years, Taiwan’s ruling Nationalists Party (“KMT” or “Guo Min Dang”) instituted martial law, subjecting any dissenters – or those who the government believed to be dissenters – to arbitrary imprisonment, torture, and death. At times, the White Terror even made its way to U.S. shores, such as assassinations sponsored by the KMT.

The world knows little of the White Terror because of the KMT’s effective suppression of the topic even after martial law was lifted in 1987. And also because of Taiwan’s friendship with the U.S., which didn’t ask the questions it should have even when U.S residents and citizens were subject to the White Terror, let alone ordinary Taiwanese. Then, came the mid-1990s, when Chinese studies in the U.S. began to focus on the mainland, with Taiwanese history an afterthought, if even that.

Now though Taiwan is on the rise. With its successful containment of COVID-19 and its strong embrace of democracy, the world is watching Taiwan. And another example that Taiwan can offer to the world is how a country deals with the mass violence and murders of its own people. In 2018, the Taiwanese government instituted the Transnational Justice Commission to investigate and address the atrocities committed during the White Terror.

To even contemplate if the Transnational Justice Commission will be successful, knowledge of the violence and pervasiveness of Taiwan’s White Terror is a must. Shawana Yang Ryan’s Green Island, a historical novel that tells the story of a Taiwanese family trying to survive the White Terror, provides that understanding.

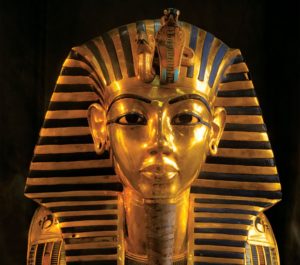

Green Island starts on the eve of the 228 Incident, with the birth of its narrator who remains nameless throughout the entire novel. Her father, a doctor, delivers her, but the next day he is violently hauled off by the police, all because of a brief moment when he spoke, in public, about his desire for a freer Taiwan. He returns to the family 10 years later, unrecognizable after a decade of on Green Island, the island where the KMT set up its diabolical prisons for political dissidents. Ryan briefly details the father’s torture, covering only the time period soon after his detention; Ryan does not go into the gory details of his decade-long prison sentences. But what Ryan shares is enough to know that the father will emerge – if he emerges at all – a very broken man. And by telling the story through the daughter, we see the intergenerational damage of the White Terror: a distant, destroyed father, who will never be able to hold a job again nor the respect of his family; the constant surveillance by the authorities; the crushing of civil society; family and friends forced to turn on each other to save another or sometimes just themselves; the retribution experienced by family members in Taiwan when an emigrated child exercises her freedom of speech in America.

Green Island is not an uplifting novel, nor can it be given the truth it seeks to expose about the KMT’s martial law. Even the narrator is a complex character, where at points you are rooting for her but then at others are appalled by her choices. Although on some level, you wonder – would I have made the same choice if put in such a horrific situation, and are thankful that your government never has asked you to. With Ryan’s artful prose and development of characters over a 60-year time period, Green Island is a necessary read to learn about the White Terror and to understand the trauma that Taiwan still grapples with even as it establishes itself as a vibrant democracy.

Rating:

Green Island: A Novel, by Shawna Yang Ryan (Penguin Random House, 2018), 400 pages.

Interested in purchasing the book? Considering supporting you local, independent bookstore. Find the nearest one here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email