Book Review: Paul French’s City of Devils

Paul French, the author of the acclaimed true crime book Midnight in Peking is finally back. It’s the 1930s again, Japan is on the march, brutally invading China, but in City of Devils: The Two Men Who Ruled the Underworld of Old Shanghai

, French’s thrilling new book, the foreigners who occupy Shanghai’s International Settlement could care less. As China burns and the rest of the world goes to war, these “Shanghailanders” frolic in neon-lighted nightclubs, gamble their immense wealth at the newest roulette tables, and drink and smoke opium till their hearts content. Their frivolous lifestyle propped up by a seedy network of gangsters, ex-cons and grifters.

City of Devils follows the two most influential characters of that underworld – “Dapper” Joe Farren, a.k.a. Josef Pollack, a Jewish-Viennese émigré who uses his dance skills and panache to set up some of the Settlement’s best music and dance acts, and “Lucky” Jack Riley, a.k.a. Fahnie Albert Becker, an American ex-con, who escaped prison, and with no passport, papers or identity, fled to the only city that would take him: Shanghai. Starting with nothing when they arrive in the late 1920s, the two would build an empire of sin, Farren with the night acts and Riley with slot machines, the one gambling device that was not declared illegal in the Settlement, very much an oversight of the law. In the clipped speech patterns of a 1920s gangster film, French recounts Farren and Riley’s decade-long rise and their unique business methods, methods that would eventually catch the eye of the United States government.

Meticulously researched and eloquently written, French captures the feel of the time period and the lawlessness that seemed to flourish in Shanghai’s International Settlement, especially after the Japanese takeover of Shanghai in 1937. The Japanese did not invade the International Settlement or the French Concession when they took Shanghai, allowing the foreigners to go on living their lives as if nothing was different. But for many Shanghailanders, the writing was on the wall with Japan’s continuous advancement in China. Those Westerns who could get out of Shanghai, did. By late 1937, early 1938, the only foreigners left in Shanghai or those who had no choice – Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust, earlier Jewish émigré like Farren who can’t go back to Europe, White Russians who fled the Bolshevik Revolution, people like Riley with a crime record so long, that arrival back to the United States would only mean prison, and businessmen and their families whose finances were so entwined with Shanghai that leaving did not seem possible.

It is with 1937 that French’s story really peaks, with Riley, Farren and a slew of other colorful characters all but running the International Settlement. Because of an increase in opium smuggling to the United States, the U.S. government sends over government agents to try to break up some of the criminal gangs. But their limited resources are no match for the wealth of the underworld. Nor for a society that seems more intent on protecting the Rileys and the Farrens of Shanghai so that their evening entertainment can continue unabated.

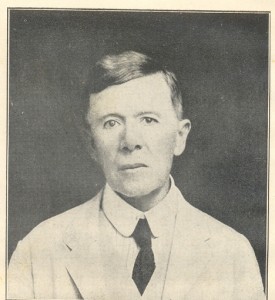

Young Victim of the Battle of Shanghai

But while many of French’s characters are blissfully ignorant of the world outside of the Settlement, French is emphatically not. At no point does he allow the reader to forget the human suffering brought upon the Chinese people with the ruthless advancement of the Japanese army. Only a few months after the fall of Chinese Shanghai comes the rape of Nanjing, an orgy of violence perpetuated on a civilian population, the scale of which the world had not seen before. But the Battle of Shanghai, considered one of the bloodiest battles of the war, also reaped destruction, taking the lives of over 300,000 Chinese citizens. And even after that battle, the Chinese continued to suffer. While the Shanghailanders of the International Settlement sip their imported champagne, Chinese citizens were starving to death, collapsing and dying in streets by the truckload. Often their bodies just left to rot. In a particularly harrowing detail, French describe the hundreds of coffins filling up local coffin storage building, with the hope that the burials will occur before the spring when the bodies begin to thaw. It is that contrast in experiences that leads to the reader’s ultimate disgust with the Shanghailanders. Eventually history would catch up with them, with the Japanese invading the International Settlement almost immediately with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

French does an amazing job of describing the Shanghai of the 1930s, a brief time period that has been romanticized by many, but that French looks at with a more honest eye. It is true that French takes many liberties and embellishments with the private thoughts and conversations of many of his characters – the real people who did exist – and that has opened him to some criticism. But that is the genre that French has created – a novel-like feel based on true facts. Facts that French acquired through years of researching the archives of the International Settlement, of the foreign police in Shanghai and the various foreign courts (see French’s recent interview on the Sinica podcast for more detail on his research). Certainly the criticism is fair, and perhaps a bibliography listing the sources French used could have been informative as well as interesting. And it might have been better to put the glossary of Chinese and other foreign words at the front of the book to help those not familiar with the words. But other than, this is a fun read.

Rating:

City of Devils: The Two Men Who Ruled the Underworld of Old Shanghai, by Paul French (Picador, 2018), 246 pages.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email