Bloomberg & Censorship: A Harbinger of What is to Come?

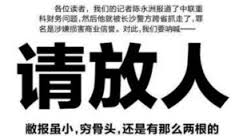

In June 2012, Bloomberg News’ China coverage was considered cutting edge. It’s China team had published an investigative piece that unmasked the enormous wealth accumulated and hidden by current Chinese President Xi Jinping and his family. For its courageous China coverage, Bloomberg won a prestigious George Polk Award here in the U.S. But back in China, the accolades were less than forthcoming. Instead, Bloomberg received the Chinese government’s retribution with its website blocked, its journalists experiencing increasing difficulty renewing their visas, and its computer systems penetrated by Chinese hackers. Evidently it’s coverage hit a nerve.

In June 2012, Bloomberg News’ China coverage was considered cutting edge. It’s China team had published an investigative piece that unmasked the enormous wealth accumulated and hidden by current Chinese President Xi Jinping and his family. For its courageous China coverage, Bloomberg won a prestigious George Polk Award here in the U.S. But back in China, the accolades were less than forthcoming. Instead, Bloomberg received the Chinese government’s retribution with its website blocked, its journalists experiencing increasing difficulty renewing their visas, and its computer systems penetrated by Chinese hackers. Evidently it’s coverage hit a nerve.

Fast forward a little over a year and last November, allegations of self-censorship regarding its China coverage engulfed Bloomberg News. According to unnamed Bloomberg reporters, editor-in-chief Matthew Winkler killed what would have been another investigative piece exposing the deep and corrupting ties between one of China’s wealthiest men and the top leadership of the

Chinese Communist Party. Allegedly Winkler feared that if the story was published, Bloomberg journalists would be kicked out of China and its China offices effectively closed. Winkler denied the allegations, informing the New York Times that the piece had in fact not been pulled. Even with these denials, Bloomberg quickly suspended the lead reporter on the story and the executive editor of Bloomberg’s investigative news division who also was an on its June 2012 China story, Amanda Bennett, left the company shortly thereafter Coincidence or sign that journalism takes a back seat to business? Recent events point toward the later.

Should We Be Surprised That Bloomberg’s Priority is Its Bottom Line?

By early 2014, it appeared that things had died down for Bloomberg’s beleaguered China team. But in March, the accusations of self-censorship re-emerged. First was Peter T. Grauer’s, chairman of Bloomberg News’ parent company Bloomberg LP, admission that some China stories it “should have rethought” when discussing Bloomberg LP’s China business. Then, only days later, longtime Bloomberg employee and editor-at-large for Asia news, Ben Richardson, vocally departed from Bloomberg and explained to media critic Jim Romenesko that “[he] left Bloomberg because of the way the [November 2013] story was mishandled, and because of how the company made misleading statements in the global press and senior executives disparaged the team that worked so hard to execute an incredibly demanding story.”

But while self-censorship – if that is what is going on Bloomberg – is always disappointing, in Bloomberg’s case, it shouldn’t come as a surprise. Bloomberg News is only a negligible part of Bloomberg LP, at least revenue-wise. Instead it is the Bloomberg Terminal, a computer that delivers real-time stock quotes, provides an electronic trading platform, and a widespread instant messaging service, that is king. Bloomberg Terminals are ubiquitous at investment banks and hedge funds; those organizations would not be able to function without them.

At $20,000 a terminal a year, it is the sale of these terminals that account for the vast majority – around 80% – of Bloomberg’s revenues. According to Dean Starkman, an editor at Columbia Journalism Review and author of The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism, Bloomberg News was always meant to play a supporting role. When Winkler founded the news division in the early 1990s, “Bloomberg was explicit about creating a new model, integrating business and editorial, where the two would work together” Starkman told China Law & Policy in a phone interview. In fact, according to Starkman, it was only in the last five to ten years, with the financial crisis, that Bloomberg News started to get more serious about journalism and rose in prominence. It was in that period that Bloomberg News won various awards for its coverage in many parts of the world.

But when a company gets 80% of its revenue from a single product it is important that its other lines of business do not hurt that

product. Here, Bloomberg’s China coverage most likely violated that business tenet. After the June 2012 publication, sales of the Bloomberg Terminals in China came to a halt. But China, unlike the United States which accounts for 37% of Terminal sales and Europe which accounts for 35% of sales, is far from a saturated market. In fact, China only accounts for a mere 3,000 Bloomberg Terminals (the tiny island of Hong Kong accounts for more than 20,000 Terminals).

To be shut out of China would jeopardize Bloomberg’s ability to increase its revenue, all at the time when its main competitor, Thomson Reuters, is gaining market share. In 2010, Thomson Reuters sought to take advantage of the financial crisis by creating the Eikon, a cheaper competitor to the Bloomberg Terminal. Although Eikon had a shaky start, its growth more recently has been phenomenal (but many in the industry still view it as inferior). In 2013 it tripled the number of Eikon subscriptions to 122,000. A scary prospect for Bloomberg.

Given that Bloomberg’s cash cow – sales of its Terminal – took a major hit after the publication of the article on Xi Jinping’s family wealth and that its battle with Eikon will be on mainland, it is not surprising that Bloomberg potentially killed another news article that would have hurt its bottom line.

Should We Be Concerned That Bloomberg is a Harbinger?

It’s no secret that the titans of the media world have taken huge hits with the influx of the internet. The Graham family’s recent sale of the Washington Post to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is one such example. For the business side of journalism, it’s not just about the bottom line, it is about survival. With this mindset, will every media outlet that covers China soften its coverage?

“No” Starkman emphatically told China Law & Policy. “[Bloomberg] is different from other media companies. Other than Reuters, no other media company has as much to lose in China.” Even when raising the issue of the New York Times and its Chinese language website which is blocked in China, Starkman was still optimistic. “The New York Times doesn’t have to be there as a business; it’s just there as a newspaper. There is no critical need for them to grow in China.” Bloomberg on the other hand, very much has a need to grow its Terminal business in China.

For Starkman, the decline in ad revenue is precisely the reason why media organizations will be forced to provide hard-hitting coverage of places like China: “The fact that news organizations rely more on subscribers [for revenue] makes it all the more imperative that. . . their news coverage remains uncompromising.” By relying on subscribers, the game comes down to credibility – if you publish less than the truth, you will no longer be credible. For the traditional media outlets like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal credibility is paramount. But as Starkman pointed out, if readers doubt Bloomberg News’ articles, it ultimately does not affect their business because they still have Terminals to sell.

For Starkman, it is this need for credibility that could potentially drive newspapers to do more investigative articles, not less.  “Investigative pieces cover something everyone knows about but it hasn’t been documented” Starkman told China Law & Policy. Corruption in China was one example that he provided; it’s well-known fact but few have been able to document the evidence as powerfully as the New York Times and Bloomberg News. “As the gap between what everyone knows and what you cover becomes wider, you lose your credibility.”

“Investigative pieces cover something everyone knows about but it hasn’t been documented” Starkman told China Law & Policy. Corruption in China was one example that he provided; it’s well-known fact but few have been able to document the evidence as powerfully as the New York Times and Bloomberg News. “As the gap between what everyone knows and what you cover becomes wider, you lose your credibility.”

And it is true. When it comes to China coverage, the go-to newspaper is increasingly the New York Times. Why? Because it is able to provide the in-depth, uncompromised coverage about what is really happening in China. Part of this of course is resources. As Bloomberg’s former editor-at-large, Ben Richardson told CNN, these type of investigative pieces are extremely expensive and difficult to produce. Large media outlets like the New York Times and Bloomberg have these resources.

Another entity that has the money and expertise to publish investigative pieces on China’s corruption would seem to be the Wall Street Journal. But they have yet to publish anything on China as in-depth as what the New York Times and Bloomberg covered. Starkman did not blame this on self-censorship but rather a changed model of news reporting where shorter pieces predominate. As the Columbia Journalism Review has documented, since Rupert Murdoch took control of the Wall Street Journal in 2007, longer pieces have precipitously plunged. “What’s the good of covering small incremental things if miss the one big thing” Starkman mused.

Bloomberg’s apparent self-censorship is disheartening especially for the reporters who likely worked really hard on the piece that appears to have been killed (six months later it still has yet to be published). But the Bloomberg Incident itself doesn’t signal the death knell for investigative journalism in China. To maintain its monopoly on China credibility, the New York Times will likely continue its hard-hitting pieces for as long as China allows it to have journalists there. It is that credibility that impacts the Times‘ bottom line. Until of course Bloomberg purchases it.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email