60 Minutes Goes Light on Alibaba

Jack Ma watching the Alibaba IPO go live at the New York Stock Exchange

With Alibaba’s IPO setting a record-breaking offering price last week, the Chinese e-commerce company’s founder and executive chairman, Jack Ma has become something of a media darling. That was readily apparent on 60 Minutes this past Sunday, where Lara Logan’s interview failed to press Ma on some of the more apparent issues. Namely, Alibaba’s relationship with the Chinese government.

To be sure, Ma’s story is impressive, especially in a country where success is often determined by connections. Ma was a no one. As a kid, when China began to re-open to the West in 1972, he escorted foreign tourists to practice his English. But that initiative did not translate into a successful academic record. Instead, Ma failed the college entrance exam twice, passing it on the third time to attend Hangzhou Teacher’s Institute. Eventually he graduated, becoming a much loved English teacher and starting his own translation company.

That would be the end of Ma’s story except that in 1995, Ma took a trip to the United States, learning for the first time about the world wide

Jack Ma’s early Alibaba team

web. The trip would change Ma and China. Upon his return, Ma started China’s first web company, China Pages. While that company would eventually flounder, in 1999, Ma created China’s first e-commerce website for business to business sales. That company – Alibaba – would spawn China’s consumer e-commerce (think ebay) websites Tmall and Taobao. With an innate understanding of Chinese consumers and what they wanted, by 2005, Taobao would surpass ebay as the dominant consumer e-commerce company in China. Last year alone, consumers spent over $272 billion on Taobao and Tmall. Alibaba, and its related consumer websites, have become a force that cannot be ignored by Western companies.

As the 60 Minutes interview revealed, Ma got into the internet when no one in China was yet able to envision its power. And that is what makes Ma so impressive – his ability to see, before anyone else did, how the internet would reshape commerce . But for Ma in 2014 to maintain, as he did in the 60 Minutes interview, that even today his company has little dealings with the Chinese government is just preposterous. According to Ma, “you can love” the Chinese government, but you “do not marry” it. But this makes no sense in a country where the government can determine the winners and losers. Unfortunately, Logan didn’t press Ma on this point even though in a voice over, she vaguely acknowledged Alibaba’s government connections.

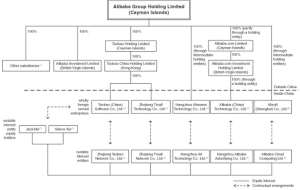

Alibaba could not succeed in China without the approval of the Chinese government as Alibaba’s own prospectus makes clear (see p. 43 – Risks Related to Doing Business in the PRC). And it would be strange if Ma wasn’t somehow courting the favor of political elites. The very corporate structure that Ma used to establish its IPO – a Variable Interest Entity (VIE) – is not particularly legal in China. As a U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission report (“the Report”) points out, VIEs are created by internet companies for the sole purpose of circumventing current Chinese law that caps foreign investment in internet companies. As the Report makes clear, VIEs are under increasing attack. In 2013, the Supreme People’s Court – China’s highest court – found a VIE illegal stating that it was being used to clearly circumvent the law. Other government agencies, including the Ministry of Commerce and the China Securities Regulatory Commission, have questioned the role of VIEs.

But this is China so questionable legal authority for a corporate structure does not necessarily signal its death knell. The Alibaba VIE will likely not end anytime soon, even with this recent assault on the corporate structure. But that has more to do with the Chinese political elite’s aligned interest in Alibaba’s success. And that aligned interest has to do with Jack Ma’s positive relations with at least some in the Chinese government. But Logan did not ask about this. Nor did she ask why Alibaba has not come under the purview of China’s Anti-Monopoly Law (AML). In becoming China’s e-commerce giant, Alibaba has acquired many of its competitors and has broadened its business to include cloud computing, an online payment system, and even financial services such as money market accounts. But even with all of this, Chinese regulators have been silent regarding Alibaba’s actions vis-a-vis the AML.

Wen Jiabao’s son, co-founder of New Horizon Capital, and Alibaba investor, Winston Wen

In fact, Alibaba’s government connections go deep, a fact that Ma left out of his interview and that Logan chose not to pursue. As the New York Times reported this past July, in 2012, $7.6 billion in shares was transferred from Yahoo! to some of China’s most well-connected private equity firms: Boyu Capital, co-founded by former President Jiang Zemin‘s grandson; CDB Capital and its Vice-President He Jinlei, son of former Politburo Standing Committee member He Guoqiang; and CITIC Capital, with Jeffrey Zeng, former Vice Premier Zeng Peiyan‘s son, at the helm. In another transaction, New Horizon Capital, a fund co-founded by former Premier Wen Jiabao‘s son, also bought a significant number of shares in a private placement.

It would be foolish to invest in a company with questionable legal authority that didn’t have strong ties to China’s political elites. On some level, for Alibaba to maintain its dominant market position, expand into other services, and ultimately succeed, it has to be “married” to the Chinese government. Why Lara Logan didn’t press Jack Ma on this is anyone’s guess but it was another unfortunate softball interview on 60 Minutes.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email