Just For Fun: Uighur Resturant Review – Cafe Kashkar

In this week’s Just for Fun section, guest blogger Thomas Cantwell, reviews the only authentic Uighur restaurant in all of New York.

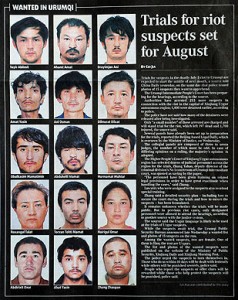

Despite having a rich history, the Uighur (pronounced Wii-grrr) have largely flown under the radar of American consciousness until the recent violence in Urumqi which resulted in the death of nearly 200 people. The Uighur, a Turkic Muslim ethnic group living mainly in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region in the northwest of China

dominated the region for nearly a millennium before falling under Chinese control. Absent an arduous journey through rural China, the closest one can get to Uighur culture in New York is a visit to Cafe Kashkar, a Uighur restaurant in Brighton Beach.

Cafe Kashkar is definitely a cultural experience, though possibly more of a Brooklyn one than anything Uighur. Not having been to Xinjiang, it is difficult for this reviewer to judge whether the region is marked by unflattering florescent lighting, exact replicas of Alice Kramden’s kitchen furniture, and carpet so ugly it would embarrass a pitboss. The nonstop Uzbek music videos–think Bollywood thumping tunes sung by better-looking Borats, backed up by big-haired tramps dancing suggestively–played on the flatscreen television mounted above the cafe’s door do attest, however, to the pan-national character of the Uighur–significant populations are located throughout all of the Stans.

While not a choice for a romantic night out, one doesn’t go to Cafe Kashkar for the decor. My companions and I ordered a number of dishes that arrived as they were prepared, which seemed fun at Kashkar, with its tiny one-man kitchen, as

opposed to pretentious as it does at, say, Asia de Cuba. First was the Salad Langsai, a mix of cucumbers, peppers and another couple of unidentified vegetables in a vinegary/garlicky dressing. It was crisp and refreshing–perfect for a warm summer evening. Next came the Kashkar Soup, which contained lamb, vegetables, and noodles in a tasty lamb broth. The soup was light and satisfying. The server–probably the nicest waitperson in all of New York City–next brought out the naan which, aside from being made from grain, bears virtually no resemblance to its Indian namesake. A sort of giant, slightly-less dense bagel, the naan was bland and virtually tasteless, though it did serve as a vehicle for sopping up the remnants of the various soups and sauces.

Next up was the best dish of the night, the geiro lagman, a slightly oily noodle dish with meat (lamb, again) and vegetables. The noodles were thick and the sauce just spicy enough to be interesting without

overpowering the taste of the meat and veg. We could have ordered another.

The manty, four giant dumplings stuffed with–you’ve got it–lamb (though mixed with beef just to shake it up a little) was so heavily laced with cumin that it tasted like cheap enchilada filling. Apparently wildly popular–you can buy frozen manty to go–you can secure a similar taste at any Taco Bell without having to haul all the way to the beach. The lamb kebobs, four fatty pieces of ribmeat that tasted of the grill, were enjoyed by my companions but I found them disappointing. Perhaps I was on lamb burnout by then.

Dessert consisted of chak chak, the only menu option available. Best described as a giant Rice Krispie treat made with honey rather than marshmallows, it was mildly sweet. American palates accustomed to sugar-laden desserts might be disappointed, though I found it a nice, light closing to the meal.

Cafe Kashkar has no liquor license, but our server specifically offered at the start of the meal the suggestion that we might secure beer from a nearby gas station. The Russian trio at the next table choose to enhance their dinner with a liter of off-brand vodka. We stuck with some pear and pomegranate/blueberry flavored soda which the server described as “Soviet” in origin and whose name I failed to note but that I’d definitely have again.

The total, before tip, was $41, a steal given the amount of food consumed. We tipped huge as the service was excellent. I’m not certain if Cafe Kashkar is worth a trip from the other boroughs–particularly in light of the upcoming suspension of B line service, which means a person could get to Philly faster than Brighton Beach from midtown Manhattan–but, if one finds oneself in Brighton Beach, Cafe Kashkar is a great alternative to New York standbys like pizza. Plus, it’s really, really fun to be able to have an excuse to use the word “Uighur”.

Rating:

Cafe Kashkar

1141 Brighton Beach Ave

Brooklyn, NY 11235-5903

(718) 743-3832

- Cafe Kashgar

- Salad Langsai

- Kashkar Soup

- Naan

- Geiro Lagman

- Manty

- Chak Chak

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email