Book Review: Desmond Shum’s Red Roulette

There is a phrase that is now common in China: “to be disappeared.” It uses the passive voice, but everyone knows who is doing the disappearing: the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”). People are “disappeared” not because they committed a crime or are even suspected of one. All that they had to have done was embarrass the CCP. The last “disappeared” to make international headlines was Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai. In November 2021, after she posted on social media about her unseemly affair with a high-level government official, she was disappeared. Taken secretly from her home and held incommunicado, she’s only been seen in public when it suits the CCP. She was paraded out during the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics for heavily scripted photo ops. Since then, the CCP has kept her out of the public eye.

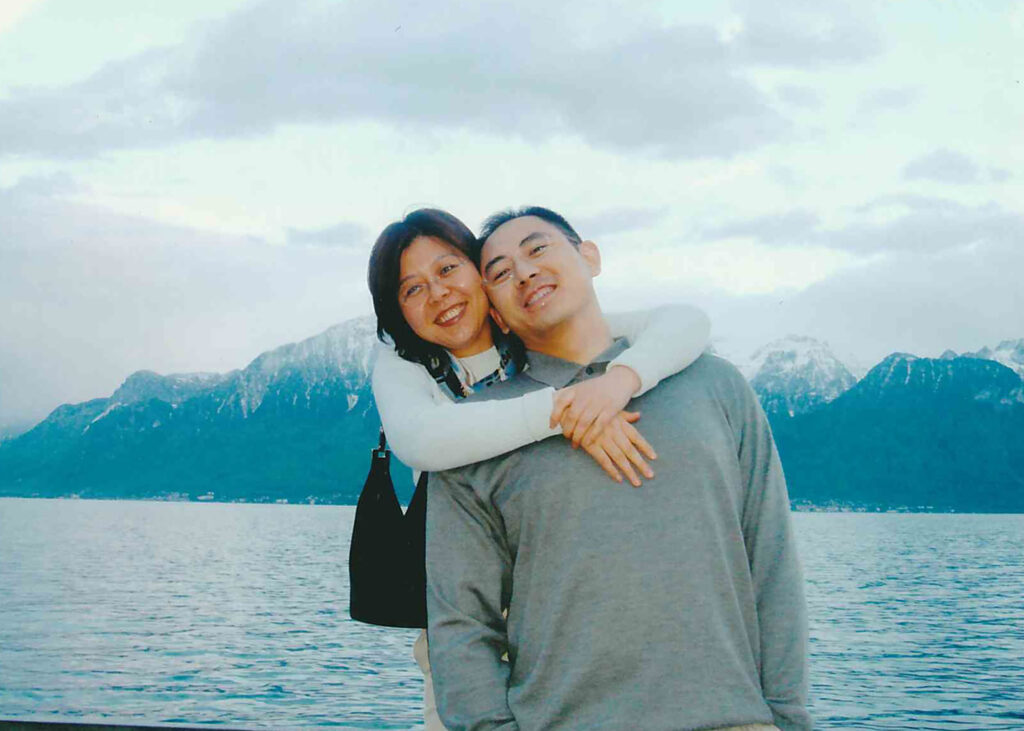

“Being disappeared” is where Desmond Shum’s Red Roulette: An insider’s story of wealth, power, corruption, and vengeance in today’s China starts. It’s 2017 and his ex-wife, Whitney Duan, has been disappeared. It is a fall from grace given that from the late 1990s to around 2010, Shum and his then-wife, Duan made billions for CCP officials and their families (and pocketed some of those billions for themselves). None of their business deals were illegal, but, with China a Communist country with state-owned enterprises running the economy and all land owned by the government, high-level contacts were necessary and in Red Roulette, Shum shows us just how much money the CCP’s elites made off of these business deals. It’s obscene. “The CCP is the epitome of capitalist excess” Shum tells us.

By 2010, people like Shum and Duan – middle men who had the moxie to grease deals between the state-owned enterprises and foreign investors – were increasingly unnecessary. The CCP could now do deals it on its own and in 2012, with the rise of Xi Jinping, a crackdown on anything Western – including businessmen – had become increasingly suspect. For Shum, who was raised in Hong Kong and went to college in the United States, the writing was on the wall: it’s time to take their money and get out. But Duan, raised on the mainland, can’t fathom that any harm will come to her. She knows how to play the game, or so she thinks. With their marriage already teetering, Duan and Shum officially divorce in 2015 and Shum moves to the United Kingdom with their son.

If you want to understand China and how CCP officials enriched themselves after Deng Xiaoping re-opened the Chinese economy in 1990, Red Roulette is a must read. It’s one of the few insider accounts of how business and politics actually operated in China, and just how much CCP officials – ostensibly communist – made for themselves and their families. What’s most fascinating and which Red Roulette spends the most amount of time on, is Duan and Shum’s relationship with Zhang Peili, the wife of then-Chinese premier Wen Jiabao. In 2012, the New York Times would ran a massive expose on the wealth that Zhang – known affectionately to Shum and Duan as “Auntie Zhang” – and her children acquired through their positions and various business deals. While the New York Times expose tracked the money and the deals, from Shum, we get the inside gossip; just how greedy Zhang was; how doors opened for her (and Duan and Shum) because of who her husband was; and her two good-for-nothing children who got rich with her.

There are parts of Red Roulette that cause eye rolls – the disgusting consumption, the waste, the selfishness – but those are par for the course in a billionaire’s memoir and do not dimmish the knowledge gained about how things operated in China. There are parts of the book where Shum comes off as shallow, but to his credit, he is brutally honest about his choice to participate in the CCP’s organized protests against Hong Kong’s Occupy Central protests. In 2014, Hong Kong’s youth took to the streets to protests the CCP’s increasingly tight grip on Hong Kong. Shum, as a loyal CCP member, was asked to go to Hong Kong and organize counter-protests which he did, going against many of the values he even then believed in and believes in even more today.

Red Roulette is an eye-opener on how business was done in China and just how quickly the Party can turn when it’s secrets are known, even on those who thought they were helping the CCP. “Repression and control are the foundations of the Party” Shum states at the end of his memoir and there are no signs that the adage is any less true today. Duan eventually emerged from her “disappearance” in 2023 in a very staged event at a business conference. But her public appearances are limited and its unclear how often Duan can see her U.K.-based son, now a teenager, if she can see him at all.

Rating:

Red Roulette: An insider’s story of wealth, power, corruption, and vengeance in today’s China, by Desmond Shum (Scribner, 2021), 320 pages.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email