Teng Biao – His Tiananmen Awakening

Human Rights Lawyer Teng Biao

In commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre, China Law & Policy continues its interview series of various eyewitnesses to this history. Today we are joined by Teng Biao. Teng Biao received his doctorate of law in 2002 from Peking University. He became a lecturer at the China University of Politics and Law while he continued as a rights lawyer and advocate. Teng Biao litigated and represented some of China’s most important civil rights cases, including the Sun Zhigang incident, he served as counsel to rights advocates Chen Guangcheng and Hu Jia, and also worked on overturning a death sentence in the Li Peng case in Jiangsu province. In addition to his individual work, Teng Biao is the co-founder of two important Beijing based NGOs that seek to protect the rights of China’s most vulnerable, China Against the Death Penalty and The Open Constitution Initiative. As a result of his advocacy on behalf of China’s most vulnerable, Teng Biao has been detained many times by the police and authorities in China.

Since 2014, Teng Biao has been living in the United States where he was a visiting scholar at the US-Asia Law Institute at NYU Law School. In the United States, Teng Biao has continued his advocacy for the rule of law in China, and for rights protection there, co-founding the Human Rights Accountability Center. But more importantly for today, back in 1989, Teng Biao was in China.

Listen to the full audio of the interview here (total time 26 minutes):

Additionally, you can read the transcript below or Click Here To Open A PDF of the Transcript of the Interview with Teng Biao.

CL&P: So, Teng Biao, I want to thank you again for joining us today. Just to get started, can you tell us where you were in the spring of 1989 when the pro-democracy demonstrations started in Beijing?

TB: I was a high school student in Jilin province. I lived in a small town in a rural area.

CL&P: What year were you back then, in 1989? How old were you in high school?

TB: First grade [of high school], I was 16 years old.

CL&P: And in your high school, when the pro-democracy demonstrations started in Beijing, were the students aware of them? Did you hear the news about them?

TB: Yes. We watched the official television, but we didn’t talk about that too much.

CL&P: Okay.

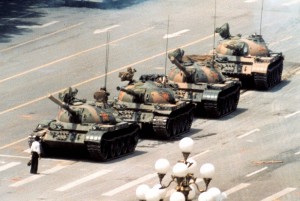

Protests in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, spring 1989

TB: I think almost all the high school students in rural areas and small towns work very hard to prepare the college entrance examination. So I knew, but I didn’t know the truth of the Tiananmen movement and massacre.

CL&P: Yeah. And then the night of June 3rd into the morning of June 4th 1989, when there was the massacre in and around Tiananmen Square, do you remember hearing the news about that?

TB: No. Actually, most of the students, including me and most of my classmates, maybe 100%, were brainwashed. We were brainwashed so much that we didn’t know everything other than the textbooks or what the teacher told us, and we never challenged what the teachers, what the official media told us, and we didn’t have any access to the books, any materials that the Communist Party prohibited.

CL&P: So you’re saying that when the Tiananmen Square massacre happened, you guys weren’t aware of it, and then afterwards they tried to brainwash you into thinking. . . .What was the party line that they were teaching at that time, if you remember?

TB: Yeah. We saw something on the television, and we knew that students were on the street protesting against corruption. But we were taught that it was a violent riot, and some soldiers were killed by the students and the Beijing citizens. And we were even actually forced to memorize the names of the soldiers who were killed.

CL&P: Oh wow.

TB: Yeah, and I can remember their names even today, two of the three, that Liu Guogeng and Cui Guozheng, and because we had to memorize these names. They were a part of the political examination. So, for me, I didn’t have the capacity to challenge the official version of this, of Tiananmen.

CL&P: Right, right. And I think it’s important that you mention that they were soldiers that were killed in the Tiananmen protests, but at the same time the students themselves were also injured and killed. When did you start realizing or learning that you hadn’t been taught the full truth, and the full facts about Tiananmen?

Wang Dan, one of the protest’s leaders, stands in front of a sign that says Peking University

TB: That’s two years later. Two years later I went to Peking University, but because of the Tiananmen, all students, the first year students of Peking University and Fudan University had to go to junxiao [军校], military college, to have a whole year of military training. But some classmates of mine brought some books, underground books written by the overseas dissidents and some other democracy thinkers. So I personally knew the truth of Tiananmen from these books, and also some classmates from Beijing, Shanghai, these big cities also told us a lot of stories they saw. They participated in the movement, and they were eyewitnesses of the Tiananmen massacre. So, two years after 1989, I knew the truth.

CL&P: And when you learned about what really happened in Tiananmen, what was your reaction? Or how did you feel?

TB: I was really shocked, and that’s the beginning of my awakening. You know, I was brainwashed, and I didn’t have the ability to think independently. So that’s the beginning of my thinking independently. And I was so shocked that I started to read a lot of books, and I realized that many, many history knowledge that I was taught [in school] was false. So I realized I had been cheated by the Chinese Communist Party for so many years, since primary school.

CL&P: And when you were there in Peking University, this would have been a couple of years after the crackdown, were other students. . .I mean I know some stories from Beijing and Shanghai, as you said, introduced you to what really happened, but what was the majority of students? Did they talk about it? Did professors talk about it? Because Peking University, they played a large role, their students, in the 1989 Tiananmen protests, right?

TB: Yeah. Between 1989 and 1992, 93 the political atmosphere was very, very supressive. People were so disappointed and they were so afraid of talking about these sensitive things. So, some of my classmates were interested in talking about political issues and human rights, but the majority of the college students never talked about it. And the majority of Chinese people, not only students, became more and more cynical and politically indifferent. Yeah, so only a few of my classmates later participated in some political activities, and they also, of course, got punished.

CL&P: And when did you decide that you wanted to go to law school, or to study law, I’m sorry, to study law?

CL&P: And when did you decide that you wanted to go to law school, or to study law, I’m sorry, to study law?

TB: In China we have law school in undergraduate, so because I was brainwashed, so I didn’t know the meaning of entering the law school, the meaning of law, or human rights, or democracy before I went to college. So I had really good scores, so I just registered at the best university in China, and I went to Peking University. So, only four or five years later I got my bachelor degree, master degree, and PhD in law school. So I think four or five years after studying law, I gradually knew the meaning of studying law. Especially in the Chinese context, I think it’s really useful to know the law and politics and we should do something to improve, to promote rule of law in China.

CL&P: In your study of the law, when did you really become, or maybe you started out very passionate, about human rights and taking your career in that direction? In deciding to be a human rights lawyer, as opposed to a corporate lawyer or something like that? When did you decide that’s what you wanted to do? Or did it happen by accident, that it wasn’t a decision?

TB: In 1999, when I started my PhD program, I decided to become an academic. I was so interested in doing research, and I want to be a professor. And to me, the idea at that time was to use my academic research and my teachings as a tool to promote rule of law in China. And at that time, human rights was not allowed to be discussed publicly. There were some academic papers on human rights, but most of them were propaganda papers. The scholars can only say that human rights is, what’s the word? Hypocritical?

CL&P: Hypocritical, yeah, yeah.

TB: Yeah. It [human rights] is a hypocritical theory of western capitalists. But several years later though, human rights was written into the Chinese constitution, and it’s more open to talk about human rights. So, after I got my PhD I began to teach at the China University of Political Science and Law.

CL&P: So, as an attorney who worked on human rights in China, and also supports rule of law, and has worked with the group of rights lawyers, the weiquan [维权] lawyers in China, as a member of that group, is there any influence of the Tiananmen crackdown on that group? Does that drive you, does that drive them to keep doing what they’re doing?

TB: Yeah. I became a lecturer and soon I practiced law as a part-time lawyer, and I dedicated myself into human rights cases. Most of my cases were related to civil rights, to these politically-sensitive cases and I was one of the earliest promoters of the rights defense movement. I found that there was a close connection between the rights defense movement and the previous democracy movement. Many human rights lawyers were influenced by the Tiananmen movement, and they were inspired by the courageous students of 1989, and some of them were also activists or witnessed the Tiananmen [protests]. Some Tiananmen activists and democracy activists joined in the rights defense movement and became part of the human rights movement. And some human rights lawyers, like me, defend not only constitutional rights using the existing legal system, but also promote democracy in China.

So, we gradually politicized the human rights movement. For example, we worked together with the dissidents, the democracy activists. And we joined the Charter 08 movement. We defend dissidents and human rights activists. And we challenge the abuse of power and corruption. So, the human rights movement in China gradually became a movement promoting democracy.

CL&P: So, you have the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown where the Chinese government opens fire on its own people. I understand why the protests are inspiring to the weiquan lawyers now and to you. But why isn’t it also something to be frightened of, that the government is willing to do something so rash? Where does the Chinese human rights lawyers and the advocates, where does their courage come from, in light of the fact that the shadow of Tiananmen hangs over them, that there could be a violent crackdown? And there has been violent crackdowns, just different, in the detentions, the mass detentions, your detentions you’ve experienced. I guess, where does that courage come from to keep going?

Sun Zhigang, migrant work killed while in police custoday.

TB: Yeah. So, for me, I think it’s my responsibility as a lawyer, as an intellectual to bear more of a burden for a democratized China. I had my PhD and I was teaching in the university, and I became a bit famous after the Sun Zhigang incident. So, [I thought] I should do more to promote democracy and rule of law in China. And in the process of human rights movement, more and more lawyers joined, and we got more and more support from the ordinary people. So, we had this feeling of solidarity, and we support each other. We were harassed, and punished, and persecuted by the authorities again and again. But we didn’t give up, and we were admired and praised by the people every time after we were targeted.

And for some other people, especially the young generation, they don’t know the Tiananmen. They may have heard of Tiananmen, but they don’t know the details of the massacre, and they are not witnesses of the Tiananmen massacre. So, of course that’s bad because they don’t have that part of the memory. But it’s also good because they don’t have the fear. They’ve never thought about the possibility of a bloody crackdown on the protesters. So, that lack of fear also inspires some people of the younger generation.

CL&P: And going back to the fact that a lot of young Chinese people don’t really know the full facts of Tiananmen, which can be good in that they don’t have the fear, but 30 years from now when we have the 60th anniversary of Tiananmen, what do you think the legacy of Tiananmen will be in China especially? Will people be able to talk openly at that point about Tiananmen?

TB: The Chinese government has been suppressing the memory of Tiananmen, suppressing the truth. And some Chinese people who commemorated the Tiananmen massacre were even been arrested and convicted [of crimes]. Chinese people now don’t enjoy freedom of expression, freedom of demonstration. So even the Tiananmen Mothers are harassed again and again for these 30 years, only because they want to commemorate their lost children, their loved ones. So, it is not possible to have a real true history, a true memory of Tiananmen if China is not a free and democratic country. So, the answer is that one, the Chinese Communist Party will step down when China can achieve legal democracy. So, I don’t know another 30 years whether or not China becomes a free country, and an open society. It’s possible, and that’s the biggest dream of many of us human rights activists and democracy activists. So we have to keep the memory alive, keep the hope alive. We have to fight for democracy and human rights. So I really hope that 30 years later, Chinese people can freely talk about Tiananmen, to commemorate the victims, and to have the freedom of expression, and a meaningful democracy.

CL&P: Well, I want to thank you again, Teng Biao, for sharing your experiences and your thoughts about Tiananmen, and also for preserving the memory for the many Chinese people in China who can’t talk about it just yet. And I also want to thank you for the amazing work you have done in China, and continue to do in trying to promote greater rights and rule of law in China. So, thank you for sharing.

TB: Thank you.

***********************************************************************************************************************

China Law & Policy will concludes its series “#Tiananmen30 – Eyewitnesses to History” with Andréa Worden, a noted China expert and, in the spring of 1989, an English teacher in Changsha, China. Hear Changsha’s story on Tuesday.

If you missed our interview with Prof. Frank Upham who was in Wuhan on June 4, 1989, please click here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58619791/915205050.jpg.0.jpg)

— as a result of certain aspects of the book being outdated (which is too be expected from a 12 year old book about contemporary China)

— as a result of certain aspects of the book being outdated (which is too be expected from a 12 year old book about contemporary China)