Margaret K. Lewis: What to Expect with China’s New CPL

Part 1 of a two part interview series with Prof. Margaret K. Lewis

This past March, after almost a year of public comment and almost sixteen years of waiting, China’s National People’s Congress finally revised its Criminal Procedure Law. The revisions were ostensibly designed to bring China more in line with the rest of the world, providing greater rights to criminal suspects and defendants.

But while the law on paper provides some greater protections, the question remains – does it go far enough. Will it ever go far enough given the immense power of China’s Public Security Bureau.

With the law set to go into effect in three months, on January 1, Prof. Margaret K. Lewis, associate professor of law at Seton Hall University and a noted Chinese criminal law expert, took the time to speak with China Law & Policy and explain many of the law’s new developments and many of its potential problems. In Part One of this two part series, Prof. Lewis explains the background to China’s Criminal Procedure Law, the different stakeholder who influenced the recent revisions, a confusing new “right” against self-incrimination and the new provisions to limit confessions obtained through torture. Will they actually work?

Click here to listen to Part 1 of this interview series with Prof. Margaret K. Lewis, or read below for transcript of Part 1.

Length: 14:35 minutes (audio will open in a seperate browser).

******************************************************************************

EL: Thank you for joining us today Prof. Lewis.

ML: My pleasure

Background on China’s Criminal Procedure Law & the Battle Over the Revisions

EL: Before we delve into the details of China’s new Criminal Procedure Law or

what is known as the CPL, can you give our listeners some background: what exactly is a criminal procedure law? Does the United States have anything like that?

ML: China has both a Criminal Law and a Criminal Procedure Law or CPL that apply to the entire country. This legal system would be more familiar to students of Continental civil-law jurisdictions than to American lawyers. There is not one unified Criminal Law that applies across the U.S. because, in addition to federal criminal law, each state has its own laws.

Now, for criminal procedure, although there are laws, regulations, rules and other types of formal legal documents that shape the criminal process in the United States, we rely heavily on case law to determine what procedures are allowed. For example, what constitutes an unreasonable search?

Importantly, in China, the Criminal Law and CPL are distinct, standalone laws with the former addressing substantive crimes and defenses—such as what constitutes theft, murder, and other crimes—and the latter addressing the process for investigating, prosecuting, and adjudicating alleged criminal activity. Yet these laws are closely intertwined.

For example, use of the death penalty is first constrained by the substantive offenses for which it is a possible penalty; this now stands at fifty-five, down from sixty-eight in the pre-2011 version of the Criminal Law—not a small number. If a person is prosecuted for a death-eligible crime, the CPL lays out the procedures that must be followed, including a final review by the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) prior to execution. How China actually uses the death penalty is still largely opaque, with the number of annual death sentences and executions remaining a state secret and estimates really range widely though generally now in the several-thousand range. That said, the trend in recent years has been to constrain the scope through both through substantive and procedural reforms.

Today in China, we have a revised CPL that will go into effect as you said in a few months. The law is written at quite a high degree of abstraction. Rumors have been swirling this summer about a forthcoming interpretation from the Supreme People’s Court that will flesh out the provisions in the law. This process happened in previous times when we had a new law and is par for the course. Most important, we need to wait to see how government authorities actually implement the law in practice.

EL: I feel like for at least the past six years, the Chinese government has been actively talking about revising and amending the Criminal Procedure Law, the CPL. Why did it do it now? Why 2011, 2012?

ML: I would emphasize at least the past six years. It’s been a boy who’s cried wolf or a Congress who’s cried law for a long time. It’s always difficult to read the tealeaves, but anecdotal reports indicate that there were deep-rooted differences of opinions among various stakeholders in the drafting process. Generally speaking, the 2013 CPL retains the same structure of the previous law but expands the number of articles from 225 to 290. The revisions themselves reflect tension and compromises between the public security forces and more reform-minded academics and other individuals involved in the drafting process.

ML: I would emphasize at least the past six years. It’s been a boy who’s cried wolf or a Congress who’s cried law for a long time. It’s always difficult to read the tealeaves, but anecdotal reports indicate that there were deep-rooted differences of opinions among various stakeholders in the drafting process. Generally speaking, the 2013 CPL retains the same structure of the previous law but expands the number of articles from 225 to 290. The revisions themselves reflect tension and compromises between the public security forces and more reform-minded academics and other individuals involved in the drafting process.

For instance, re-education through labor has long been a contentious issue. This is a police-controlled sanction which is considered administrative, not criminal, and thus does not go through the courts as would a criminal sentence. Yet the police can send someone away for three years with a possible one-year extension. Reports circulated for years that China would revise re-education through labor by including it within the CPL or creating some sort of separate court review to comply with provisions in international human rights documents or just abolish it entirely. To date, none of these proposed reforms have prevailed over resistance from the public security forces and they maintain control over the re-education through labor system.

EL: Just to follow up on that…so basically the two main stakeholders you think are the public security interests and then the academic interests?

ML: Of course there are also prosecutors, there are courts. I think the extremes are represented by the most human rights-oriented scholars—of course not all scholars agree on that—and then the real law-and-order police forces. I think it gets more complicated when you look at prosecutors and judges: their interests can cut both ways.

A New Right Against Self-Incrimination?

EL: Right, right. In talking about the generalities, you mentioned the changes or

some of the lack of changes like re-education through labor. But I want to focus now on something you have actually written about recently in your article Presuming Innocence, or Corruption, in China, [and] one of the big changes to the new CPL which is basically a right against self-incrimination which we find in Article 50. Did the previous Criminal Procedure Law not provide such a right to defendants? Is the right in the 2012 CPL similar to the right to silence that criminal suspects and defendants have in the U.S.?

ML: The right against self-incrimination in the U.S. has a complex history and its contours are notably different than the new provisions we’re seeing in China’s CPL.

The revised CPL has neither a clear right against self-incrimination nor a clear presumption of innocence. It moves in that direction but stops short. A way we commonly think of the right against self-incrimination is, as you say, a right to silence, which is included as part of the famous Miranda Rights [in the U.S.]. Anyone who has ever watched any TV knows those by heart. In China, the 2012 revisions have been lauded for providing that interrogators not force people to incriminate themselves, but this welcome addition fails to provide a clear right to silence, especially when combined with the lingering requirement that suspects must answer questions truthfully. And there’s still an overt emphasis on leniency for confessions, which puts greater pressure on suspects to be forthcoming with information.

EL: Right, and just to follow up on that. I noticed that too when I looked at the new CPL, that you have this sort-of right against self-incrimination in Article 50 and then you have what is still left in the new CPL from the old CPL, is this requirement in Article 93 that the suspect answers truthfully and that the interrogator asks questions and they have to talk about their guilt or innocence, and that they answer truthfully. How do you see those two provisions playing out, or at all?

ML: It is difficult to square Article 50 with Article 93. The best I can tell is suspects must answer truthfully, but interrogators are limited in the measures they can take to force people to talk. At base, this tension reflects the horse-trading that went on in the drafting process. We had more reform-minded drafters who wanted a robust right against self-incrimination but there was no way that this was going to get past the public security forces and other more law-and-order factions.

Evidence Obtained through Torture – Will it Really Be Excluded?

EL: That’s really interesting because I think a lot of people think China is just this one-party state and there isn’t these factions and there isn’t horse trading. And it seems like in your response, you alluded to one of the bigger things that I think a lot of people are applauding which is the adoption of provisions excluding evidence obtained through torture, especially confessions. Confessions in China are usually the basis of most convictions I believe, but correct me if I am wrong, and there has been a lot of recent stories of murder victims who appear alive and then they have to set the person free. Can you talk more about these new provisions found primarily in Articles 54 to 58 of the new CPL?

EL: That’s really interesting because I think a lot of people think China is just this one-party state and there isn’t these factions and there isn’t horse trading. And it seems like in your response, you alluded to one of the bigger things that I think a lot of people are applauding which is the adoption of provisions excluding evidence obtained through torture, especially confessions. Confessions in China are usually the basis of most convictions I believe, but correct me if I am wrong, and there has been a lot of recent stories of murder victims who appear alive and then they have to set the person free. Can you talk more about these new provisions found primarily in Articles 54 to 58 of the new CPL?

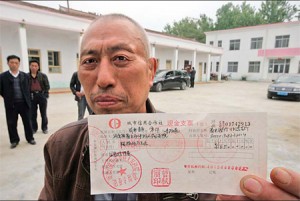

ML: Confessions still are king in China and certainly the easiest case for a wrongful conviction is when the alleged murder victim returns alive, as seen in the case of Zhao Zuohai. In that case, the murder “victim” returned to the village alive after his self-confessed “murderer” had spent a decade in prison. Obviously you don’t need DNA evidence to prove someone’s innocence when someone who is supposedly beheaded now returns to the village intact.

That case brought unprecedented public scrutiny to methods used to extract confessions. It eventually came to light that police had beaten Zhao during the interrogation process. Zhao’s case and other reports of coercion and outright physical torture prompted the release of new evidentiary rules in 2010. That included, among other provisions, a pre-trial mechanism to challenge the admissibility of illegally obtained confessions.

These new rules have largely been incorporated into the [revised] Criminal

Procedure Law and this has marked a step towards recognizing the extreme reliance on confessions and the concerns for abuse and mistakes that are inherent in such a one-dimensional method of evidence collection. Again, the new CPL is not yet in effect, but reports of defendants invoking the 2010 rules are few and news of successful challenges limited to at best a handful.

EL: Just in trying to understand how these new provisions will work, who can actually raise the issue of a confession obtained through torture and what happens once it’s raised? I think you mentioned a pre-trial mechanism to analyze that.

ML: The law provides that prosecutors should conduct an investigation on their own volition if they are tipped off that investigators used unlawful methods of evidence collection [Article 55]. But should is different than will. How enthusiastic prosecutors will be using this power is subject to doubt.

Similarly, judges should conduct an investigation if they suspect that investigators used unlawful methods of evidence collection [Article. 56].

Moreover, and most interestingly, the defense may request the court to exclude the evidence gathered by unlawful means. This is a marked change from the prior Criminal Procedure Law. However, as with the 2010 Evidence Rules, it is questionable how receptive courts will be to these applications. Defense counsel is also hampered in its ability to access evidence that would prove illegal means. And you need to have a defense lawyer who understands these rules to begin with.

There are a number of practical hurdles that stand between what the law says and what we are actually going to see in practice.

EL: Another interesting thing, and I don’t know how this works as much in a civil law country, the CPL does not define what is considered torture. Even in the U.S., there are tactics used in interrogation that while rough, are not legally torture. Are there any other regulations in China which define torture? How will the courts go about defining torture? I know it is a civil law system but will there be any, sort-of, common law definitions emerging for torture?

ML: First there is an issue of translation. The phrase you often hear in Chinese—xingxun bigong [刑讯逼供] —is often translated as “extracting confessions through torture” but it uses a different word for torture than, for example, in United Nations Convention Against Torture, which is kuxing [酷刑]. Right there, sometimes there is a little bit of questioning what we are dealing with.

To my knowledge, there is no clear definition of torture in Chinese law, but that is true in other jurisdictions as well. I think one concern is that, by giving a clear definition, it can be easier for people to inflict suffering on another person and say, “But, look, what I did is not in the definition of torture.” Sometimes there is a reason not to have the definition too clearly spelled out.

And as you point out, a related issue is what practices short of physical torture are deemed illegal; for example, coercion, lying to suspects, playing psychological games. When do interrogators cross the line from using creative, acceptable tactics to measures that society really wants to condemn.

Part 2 of the Interview to Follow

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email