Should Obama Downgrade Xi’s Planned State Visit?

Last week, China Law & Policy published a post encouraging President Obama, even in light of the current crackdown on rights defending advocates in China, to move ahead with President Xi Jinping’s State Visit to the U.S. currently scheduled for September. However, China Law & Policy recommended that President Obama raise the plight of the rights defending lawyers by highlighting the important role public interest lawyers have played in the United States.

Our posting received a plethora of responses, including one from Adam Bobrow, CEO and Founder of Foresight Resilience Strategies, LLC, a Maryland-based strategic consulting firm to develop new solutions for companies facing cybersecurity challenges. With prior experience in the White House and the Department of Commerce, Bobrow explains the procedures surrounding a State Visit and argues that while the Xi visit must occur because of many thorny issues plaguing the US-China relationship, the visit should be downgraded to an “official visit,” not a State Visit.

By Guest Author Adam BobrowThanks to Elizabeth for her original post which made me think more about Chinese President Xi Jinping’s September State Visit to Washington. Elizabeth’s thoughtful take addressed the question of the White House’s response to the crackdown on rights defenders in China. I agree that President Obama’s meeting with Chinese President Xi should go forward but I have tried to take into account additional strategic and economic policy considerations in assessing whether Xi’s State Visit seems appropriate at this time. For reasons addressed below, I do not think that incorporating a session on the crackdown will work but suggest that the White House downgrade the meeting from a State Visit to another category of Head of State visit, such as an official visit or a working visit.

The Obama-Xi meeting should take place because there are many issues that the United States and China need to discuss at the highest levels. But the pomp and circumstances and the inherent approbation of a State Visit sends the wrong message to China about the ways in which Chinese government policies impact the U.S. economy and elements of global security that the United States has vested interests in maintaining.

Background on State Visits

A State Visit, while it does not have an absolute definition, follows certain traditional guidelines surrounding its logistics and the respect accorded the foreign Head of State or Government. In the United States, such a visit has an arrival ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House, a 21-gun salute for the visiting Head of State, a joint review of U.S. troops, and a State Dinner with the visiting Head of State as the guest of honor. Because the last element is the easiest to measure—either a State Dinner occurred or it did not—I have used the inclusion of a State Dinner during a visit as a proxy for State Visits.

During the current Administration, President Xi’s State Visit would be only the ninth State Visit in the almost seven years since President Obama was sworn into office. Perhaps more telling, of those nine State Visits, President Obama will have hosted two different Chinese Presidents. No other country’s leaders have enjoyed two State Visit invitations during this Administration even though Mexico, South Korea, Japan, and India—all State Visit countries during the Obama Administration—have changed leaders since President Obama hosted their previous Head of State or Government.

Why Should Obama and Xi Meet?

In Elizabeth’s blog post, she advocates that President Obama should, “invit[e] Xi Jinping to a session with U.S. public interest lawyers and their supportive corporate law brethren” to demonstrate the United States’ support for the plight of rights defenders in China. During President Xi’s visit President Obama can and certainly should raise the unacceptable and self-defeating nature of the ongoing roundup of weiquan (rights defending) lawyers by the Chinese authorities––either by insisting that there be a window reserved in the primary bilateral meeting (preferred) or by bringing the topic up spontaneously in that meeting or at the joint press conference. The latter is less effective to change Chinese behavior but important as a domestic political issue in the United States. But keep in mind that the Chinese officials planning the State Visit will not agree to a meeting that includes some of the private critics of their conduct in the United States. The U.S. government cannot unilaterally control the broad agenda for the visit by insisting on certain meetings, such as one with U.S. public interest lawyers.

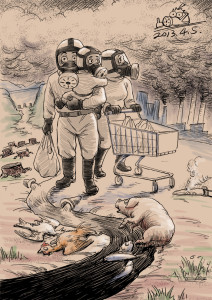

But even with this limitation, the larger question remains: why should the U.S. and Chinese Presidents meet? Currently, the United States and China face a number of urgent issues that directly impact their relationship. For far too many of these, however, neither side will agree even on the terms of reference for their differences, preferring either to deny a problem exists or to insist on a formulation that assigns the responsibility exclusively to the other party. These thorny issues are myriad: Chinese island reclamation and freedom of navigation in the South and East China Seas; alleged cyber incursions into U.S.-based systems including personnel files held by the U.S. government and commercially valuable data held by a wide range of U.S. businesses; the devaluation of China’s currency in response to slowing growth in China; the creation of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, a new international development institution created with China as the leading shareholder; national security limitations on Chinese investment in the United States; the impact of China’s own National Security Law on U.S. businesses operating in China; and even China’s continued non-market economy status in U.S. antidumping investigations. Today’s New York Times reveals another agenda item: Chinese public security agents operating in the United States and allegedly intimidating or threatening some Chinese expatriates suspected of graft to return to China. This is an additional issue for which the two countries offer incompatible explanations. Unfortunately, political leaders in both countries have framed these issues in ways that make them difficult to discuss, much less resolve.

The meeting of the two Presidents could advance bilateral cooperation, however, on two issues of current importance. First, both sides seek to advance negotiations on the U.S.-China Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) by exchanging updated negative lists of excluded investment areas. Second, each side also wants to advance cooperation on curbing greenhouse gas emissions in advance of the 21st session of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of Parties (COP 21) in Paris in December. Obama and Xi could announce concrete and meaningful progress on BIT and greenhouse gas emissions based on strong preparation at the staff- through Cabinet-levels and help provide negotiating teams on each topic with clear instructions on the way forward in both cases.

When weighing the decision of whether to downgrade the meeting, political and protocol reasons for the level of the visit must also contend with the substantive policy questions already discussed. The issue of face plays a role in this calculation as President Xi hosted President Obama for a State Visit in Beijing last year, complete with State Arrival Ceremony at the Great Hall of the People and a State Banquet. Refusing to accord President Xi the same courtesies would cause great offense. In addition, leaders meet to increase opportunities to get to know one another and build a relationship that might advance issues or prevent future conflicts. Two years ago, the White House cited this reasoning in meeting in a more relaxed setting away from Washington in the lead-up to the two Presidents’ summit at the Sunnylands Estate in California. The very specific intention of the informal setting away from Washington was to reduce the pressure to make public pronouncements and face the increased scrutiny of a scripted and formal visit so that the leaders could get to know one another better. Whether the more informal setting did allow greater candor, the added scrutiny of a State Visit can only undermine efforts by the two Presidents to build their relationship as a hedge against growing frictions in any meaningful way. Next month, the two Presidents will meet farther apart on urgent bilateral issues than at any prior meeting they have had and with often conflicting visions of the world as they would like it to be. Ranging from President Xi’s marketing of China’s New Model of Great Power Relations, which premises more space for Chinese actions on the world stage free of American interference or even commentary, to President Obama’s preference for selling the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement (TPP) as a way of writing new international trade rules to prevent China from writing those rules instead, these competing visions are not currently amenable to building trust during a one-day visit.

Where does that leave us in terms of a verdict on the impending visit? Looking at the list of issues where no progress is likely, it is probable that each President will raise a differing subset of those issues without actually hearing what the other has to say. They will talk past each other and reach no conclusions nor even advance the terms on which officials at lower levels will address these issues going forward. On the other (skimpier) hand, the Presidents may make meaningful progress on the two issues identified above: BIT negotiations and climate change measures ahead of the Paris negotiations in December. The non-policy considerations present a trickier, more qualitative question of whether the slim possibility of greater candor in a less formal set of meetings makes it a better bet to risk the strong negative reaction of a Chinese government that sees the downgrade as a personal snub to President Xi. The White House needs to decide based on the best interest of the United States and the American people, of course, rather than how its decision in Washington will be received in Beijing or even by some larger subset of the Chinese people.

In this instance, the pomp and circumstance of a State Visit will reduce the efficacy of the potential positive outcomes of the meeting and send a misleading positive message about the current parlous state of U.S.-China relations. Rather than providing additional space for the two Presidents to increase mutual understanding and provide clear guidance to their bureaucracies on how to resolve some outstanding issues, the Presidents may make some small and specific progress in two areas. But the strictures of a State Visit also make it likely that the two governments will feel compelled to send a message that the visit demonstrates a highly productive bilateral relationship on firm grounding. That message would obfuscate real differences in search of solutions, potentially setting back relations rather than moving them forward, and backfire as the evidence clearly belies such a positive message. The White House should downgrade the meeting, restore the informal approach of Sunnylands, and hope that more time focused on substance and less on meaningless public praise by each country of the other may permit more candid discussion and advance solutions to pressing problems.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

But Lim not only tells the stories of those who witnessed the crackdown, but also those for whom June 4, 1989 has no significance, namely the babies born after 1990. In one study that Lim conducted, only 15 out of 100 Chinese college students were able to identify the infamous Tank Man photo, a photo that epitomizes the Tian’anmen crackdown and that is perhaps one of the world’s greatest symbols of courage. She follows a college student who goes to Hong Kong to try to understand Tian’anmen, but when he returns to China, he just seems confused and deflated. And then there is the Patriot, a Chinese car salesman who goes to Beijing to participate in the government-sponsored protests against the Japanese. Their failure and inability to know about the Tian’anmen crackdown demonstrates the true effectiveness of the CCP’s re-writing of the Chinese people’s history.

But Lim not only tells the stories of those who witnessed the crackdown, but also those for whom June 4, 1989 has no significance, namely the babies born after 1990. In one study that Lim conducted, only 15 out of 100 Chinese college students were able to identify the infamous Tank Man photo, a photo that epitomizes the Tian’anmen crackdown and that is perhaps one of the world’s greatest symbols of courage. She follows a college student who goes to Hong Kong to try to understand Tian’anmen, but when he returns to China, he just seems confused and deflated. And then there is the Patriot, a Chinese car salesman who goes to Beijing to participate in the government-sponsored protests against the Japanese. Their failure and inability to know about the Tian’anmen crackdown demonstrates the true effectiveness of the CCP’s re-writing of the Chinese people’s history.

It’s not only the South China Sea that is witnessing China’s differing interpretation of international law and its commitments under various treaties. With its

It’s not only the South China Sea that is witnessing China’s differing interpretation of international law and its commitments under various treaties. With its  In

In