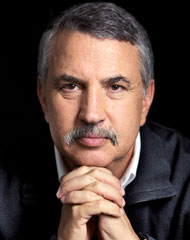

Tom Friedman on China: End of Corruption in China or Just a Woman Scorned?

“Every so often you read a news article so revealing…[and] say ‘…That story was the warning sign.”” So begins Tom Friedman’s unfortunate return to writing about China.

In Wednesday’s “Revenge of the Mistress,” Friedman feebly attempts to argue that China has reached a turning point on official corruption and that turning point has been the online blitz of one “jilted mistress” of the deputy director at the State Administration of Archives. For Friedman, this 26 year old woman, Ji Yingnan, and her online posts and photos of their lavish life together – a life she thought was forever until she found out that the man was married with a kid – are important in exposing the corruption that is prevalent in China. For Friedman, she is the whistleblower that could change the course of China and potentially of the world.

But Friedman’s article completely misses the mark and paints a picture of China that doesn’t really exist.

First, a jilted mistress as a whistleblower? Really? Do you really think that the popularity of her blog posts is a result of an never-before-exposed seeping anger against official corruption? Or is it more perhaps the lurid details of an affair that went wrong? Are the excesses she exposes really that unknown to the Chinese public?

No. The lavishness of government officials has been reported on by the domestic Chinese media for at least the past year. What Ji “exposes” are facts that are already well known. The Chinese public knows that graft and corruption is very much a part of their leadership’s lives. China’s new President Xi Jinping has openly called for the end of corruption among government officials, implicitly admitting to the fact that corruption is wide-spread.

While certain aspects of the leadership’s wealth – such as the wealth amassed by former Premier Wen Jiabao’s family and reported by David  Barboza in the N.Y. Times – have been kept a secret, the lavish spending and mistresses of some government officials has been reported. And Ji’s post in no way rises to the damning level of Barboza’s well-documented accumulation of wealth through government ties. Unlike Barboza’s series of articles which were censored in China, Ji’s posts are still on the internet and she is even receiving media attention. The reason: because she is not a threat to the ruling elite or necessarily their ways. She is not a whistleblower; she is not a game-changer; she is a woman scorned.

Barboza in the N.Y. Times – have been kept a secret, the lavish spending and mistresses of some government officials has been reported. And Ji’s post in no way rises to the damning level of Barboza’s well-documented accumulation of wealth through government ties. Unlike Barboza’s series of articles which were censored in China, Ji’s posts are still on the internet and she is even receiving media attention. The reason: because she is not a threat to the ruling elite or necessarily their ways. She is not a whistleblower; she is not a game-changer; she is a woman scorned.

But the bigger fault of Friedman’s analysis is his complete ignorance of the fact that since May, the Chinese government has waged a crackdown on anti-corruption activists, petitioners and lawyers, detaining more than 30 individuals for their anti-corruption campaigns. Most of these activists have been freed. But most recently, the Chinese government has detained well-known rights lawyer Xu Zhiyong who has called for greater government transparency and accountability of officials and their families’ assets.

To ignore the work of these activists and the largely illegal crackdown on their activism (Xu was denied access to his lawyers in contravention of the Lawyers Law and the new Criminal Procedure Law) does a disservice to explaining what is really going on in China. To claim that a “jilted mistress” is a civil society actor misinterprets what civil society is. Likely Ji doesn’t have a “cause” other than herself. The detained activists, their cause is to better Chinese society and have the government follow a rule of law.

Friedman naively calls on civil society actors to find allies within the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and convince them that cracking down on corruption is in their best interest. As if these activists – sitting in their detention cells – hadn’t already thought of that. While the CCP is not a monolith and there are some reformers within the government, it’s still not an open group of people. It’s not like some reformer in the CCP is going to invite Xu Zhiyong out for a beer summit and get his take on things. And what’s Xu suppose to do, write a letter about ending corruption? In China, that’s what gets you detained.

Finally, Friedman’s article ends by focusing on how corruption in the Chinese government doesn’t just destabilize China, but given our intertwined relationship, the United States as well. But this is too simplistic of an analysis. Certainly what happens in China impacts the U.S. But would ending corruption solve everything? Would that change the fact that the Chinese government ties its currency to the U.S. dollar? Would that result in better air quality standards in China? Largely no.

What would have a bigger impact would be a rule of law. Corruption goes unchecked because there isn’t an independent prosecutor to check local government officials. Air quality in China is horrible because environmental regulations are not enforced and the people have no independent courts in which to bring their case. Corruption is merely a symptom of the underlying disregard for a rule of law.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email