Putting One’s Life on the Line: Criminal Liability for Xinjiang Documents Leak

Last October, after denying the existence of internment camps in Xinjiang for over a year, the Chinese government finally admitted to their existence but claimed that they were nothing more than “vocational education and training centers.” Places where “students” – over one million of them and almost all Uighur and other Turkic Muslims – could rid themselves of Islamic extremism while simultaneously upgrading their job skills. But camp survivors’ stories paint an entirely different, and much darker picture. In story after story, former detainees talked about the prison-like conditions, of being held for months to years without access to the outside world, of physiological and physical abuse, and punishment solely for practicing their faith. Women have consistently spoken of rape, forced sterilization and forced abortion. Unfortunately, with the Chinese government’s refusal to allow outside monitors unfettered access to the camps, these survivors’ stories could not be corroborated.

Until now. In the past two weeks, both The New York Times and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (“ICIJ”) have published two different troves of confidential Chinese government documents (the “Xinjiang Papers” and the “China Cables,” respectively) that confirm the unlawfully detention of Uighurs in what are essentially prisons. According to the Xinjiang Papers, any direct inquiry by relatives as to whether their detained family member has committed a crime, officials are to answer no but immediately follow it up with the assertion that the their family member still needs “education” to rid themselves of “unhealthy thoughts,” likening Islam to a disease.

ICIJ’s China Cables provide even more detail into the everyday operations of the prison camps. Detainees are kept in “double-locked” rooms at all times and are constantly watched, even in the bathroom. Preventing escapes is paramount and there must not be any “blind spots” in the video surveillance of the detainees. Guards are trained in “combat exercises” to ensure their immediate response if “something happens.” Detainees are forbidden from having cell phones and family visits are never in person; only periodic phone calls and occasional video chats are permitted. Detainees are forced to remain in the center for at least a year. And while the government documents refer to the camps as “vocational skills training centers,” it is apparent from the guidance provided to the camp administrators that the focus is to Sinicize the Uighurs and stamp out their religion. In fact it is only after a year of ideological indoctrination do some – not all – detainees continue on for a three to six month “skills improvement” training, a training that is more responsive to future employers’ needs than to the individual’s.

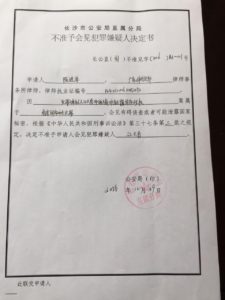

In no way did the Chinese government ever want these documents released. And the people who leaked these documents to the New York Times and to ICIJ put their lives on the line to stop the mass atrocities in Xinjiang. According to Margaret K. Lewis, a professor of Chinese law at Seton Hall University, at least some of these documents would be considered state secrets. “What is a state secret is very vague, can be defined retroactively and doesn’t need to be stamped ‘state secret’ to be considered a state secret,” Lewis told me when I asked her about the leak of the Xinjiang documents. Under China’s Criminal Law (“CL”), leaking state secrets is a serious offense, carrying a sentence anywhere from 10 years to life where the circumstances are especially serious (CL, Art. 111), which one would think is present here. A death sentence is possible if the leak causes particularly grave harm (CL, Art. 113).

“They could also be charged with subverting state power,” Lewis told me. “It’s not just what the documents were but also why they were giving these to foreigners” Lewis continued. Like state secrets, subverting state power (CL, Art. 105) can carry up to a life sentence and if the person colluded with foreigners in the subversion, arguably what the whistleblowers did here, then the law requires that the punishment be severe (CL, Art. 106). But, unlike state secrets, subverting state power is not subject to the death penalty. In pressing Lewis further on what she thought the whistleblowers would be charged with and what type of sentence they would get, Lewis was clear: “This is less of a legal question and more of a political one.” To Lewis, it will come down to what is best for President Xi Jinping: is it better to make an example of the whistleblowers, or are the whistle blowers high enough officials that publicly identifying who they are could be an embarrassment to the Chinese government, and thus their prosecution may never be public. Under Article 183 of China’s Criminal Procedure Law, state secrets trials are closed to the public.

“They could also be charged with subverting state power,” Lewis told me. “It’s not just what the documents were but also why they were giving these to foreigners” Lewis continued. Like state secrets, subverting state power (CL, Art. 105) can carry up to a life sentence and if the person colluded with foreigners in the subversion, arguably what the whistleblowers did here, then the law requires that the punishment be severe (CL, Art. 106). But, unlike state secrets, subverting state power is not subject to the death penalty. In pressing Lewis further on what she thought the whistleblowers would be charged with and what type of sentence they would get, Lewis was clear: “This is less of a legal question and more of a political one.” To Lewis, it will come down to what is best for President Xi Jinping: is it better to make an example of the whistleblowers, or are the whistle blowers high enough officials that publicly identifying who they are could be an embarrassment to the Chinese government, and thus their prosecution may never be public. Under Article 183 of China’s Criminal Procedure Law, state secrets trials are closed to the public.

“The one thing that is certain,” Lewis told me “is, if the whistleblowers are caught, they will experience long-term detention and suffering.” And their families. “You’re not just putting yourself at risk, but also your loved ones,” Lewis said. “Whoever this person is, I am grateful for the risks taken to bring the documents to light.”

These whistleblowers must have known the high costs associated with leaking the documents. But still they determined that it was worth it; that the world must know precisely what is happening in the Xinjiang prison camps; that Uighurs are unnecessarily suffering at the hands of the Chinese government; and that it must be stopped. But since the release of the China Cables on Sunday, only the United Kingdom and Germany have demanded that China provide unfettered access to United Nations human rights observers. But where is everyone else? Where is the United Nations’ response? Will Antonio Guterres, the current Secretary General who has stayed mum for the last two years about China’s treatment of Uighurs, finally condemn China’s actions? And while the United States issued a strong statement, it could do more. The Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act is just sitting in the House; the State Department has yet to call call for the UN to be given unfettered access to Xinjiang; and Treasury makes no mention of Maginsky Act sanctions against some of the high-level officials named in the Xinjiang papers. And what about Australia, Japan, Canada, or any of the Arab nations? Finally, where is the International Olympic Committee? Do we really want Beijing’s 2022 Olympics to be a replay of Nazi Germany’s 1936 Games?

I can only hope that in the next few days I can add more countries to this post as ones that spoke out. But more than anything, I hope that these countries and organizations unite to take action to stop the crimes against humanity currently occurring in Xinjiang. Individuals in China have put their lives on the line. It’s time the rest of the world follow suit and have the courage to act.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/business/2019/01/03/china-says-no-doubt-two-detained-canadians-broke-law/untitled_design_3_.jpg)

But, starting with the

But, starting with the