Who Will Be Watched: Margaret K. Lewis on China’s New CPL & Residential Surveillance

Part 2 of a two part interview series with Margaret K. Lewis. Click here for Part 1.

After 16 years and a world of changes, China finally revised its Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”). Implementation is set to take place in three months. So the question remains, is China ready for these changes? Are the lawyers aware of how these changes will impact their practice? Will we see a different landscape?

As Margaret K. Lewis, associate professor of law at Seton Hall University and Chinese criminal law expert, explained on Monday, the revised CPL was a compromise between two powerful dueling interests – reformers and the security apparatus. But who wins out? In Part 2 of this interview, Prof. Lewis continues to explain some of the major changes, including the inclusion and legalization of the public security’s use of residential surveillance. Is it better that the rules are finally written down? Read below to find out.

Click here to listen to Part 2 of this two part interview series with Prof. Margaret K. Lewis, or read below for a transcript of Part 2 of the interview.

Length: 16:02 minutes

********************************************************************************

Will Witnesses Appear in Court?

EL: Going from confessions, which form the basis of most convictions in China, I want to switch to another aspect of the CPL that I just find really, really confusing which is witness testimony. Right now, under the current CPL, or just as a general practice, witnesses usually don’t appear in court, is that right?

ML: That is right. Although we don’t have an official statistic, I regularly hear that witnesses appear in less than 10% of cases, and even that is likely being generous. The more common practice is to read written statements that witnesses gave to the police or prosecutors. Once when visiting a court in China, the group I was with toured an empty courtroom. It was beautiful: beautiful polished wood, it was gorgeous. The judge giving us the tour pointed out where the defendant would sit and where the lawyers would sit. We asked, “Where does the witness sit?” There was an awkward pause and then it was said, “Well, a chair would be brought up here for the witness.” But it was clear that this was not common practice. Again, hopefully that will change but, to date, witnesses have played a very limited role when it comes to the actual trial process.

EL: So with the new CPL, in reviewing the added provisions, I have noticed that there are a lot of provisions that talk about witnesses: compensating them for attending a trial and forbidding employers from docking pay or injuring an employee who has to go to court. I think you find that in Article 63. But then later on when I was looking through the amended CPL, we see Article 181, which seems to imply that only in rare circumstances will a witness be required to appear and if the court thinks they have to appear. Do you think based on some of these additions, but yet the retention of Article 181, do you think we will start to see greater in-court witness testimony under the new CPL?

ML: As you note, on paper, the revised CPL puts greater emphasis on witnesses appearing in court. But I share your skepticism that these provisions will lead to a marked increase in witness participation. We need buy-in from the prosecutors, from the judges in particular to welcome this change in the actual courtroom.

Again, a related issue is that lawyers remain restricted both in law and practice. The scarcity of lawyers who handle criminal cases in China combined with the highly constrained scope of publicly funded representation means that the majority of criminal defendants proceed without any counsel whatsoever. Having witnesses appear is generally of little use to the defendant unless there is competent counsel to examine, or cross-examine, the witness depending on whose witness it is.

EL: This is all really interesting because I think it shows—the fact that there is a tremendous reliance on confessions and there aren’t witnesses in court—it shows how different the Chinese criminal court system or how a trial is performed in China from the United States. If you don’t have witnesses and you have confessions, what is really going on in a Chinese criminal trial? What else happens? Or is there anything else that happens?

ML: I have only seen parts of a few trials in China—my blonde hair and white face doesn’t help—and I know those trials were selected as appropriate for foreign visitors. As a result, I cannot speak much from personal experience. Instead it is anecdotes and talking to people who have a much more intimate understanding.

But what we do know is that, the further a case progresses, the more likely that a suspect will be found guilty. China’s approximately 99% conviction rate emphasizes the need for early advocacy on behalf of suspects if there is any hope of avoiding criminal liability. The trial itself routinely focuses on whether the defendant merits lenient punishment instead of whether the evidence is sufficient to support a guilty verdict.

I believe in giving criticism where criticism is due. People should realize that here in the U.S. cases seldom go to trial. Most cases are resolved by way of a guilty plea, not a dramatic Law & Order episode in the courtroom. That said, China is still even more dramatic in its conviction rate and how trials have always been of relatively little importance.

The Controversial Provisions on Residential Surveillance

EL: Switching gears let’s go back to what goes on before the trial during the investigation phase. I think this is perhaps one of the biggest changes to the CPL and most people think for the worse—is the codification of what’s known as “residential surveillance.” Can you first explain a little bit what is residential surveillance and how the new CPL addresses it?

ML: The government’s ability to deprive people of liberty prior to conviction or even charging really was a focal point of the debates surrounding the revisions. This deprivation can occur, as you know, through [1]“residential surveillance” [jianshi ju zhu – 监视居住] though not necessarily at the suspect’s own residence, or [2] through “detention” [juliu – 居留] at what’s known as a detention house or a kanshousuo [看守所].

Following release of the draft revised CPL last summer, critics quickly pointed to the provision in the law that allowed police to hold suspects under residential surveillance in cases involving crimes of endangering state security, terrorist activity, or serious bribery. Nor would the police have to notify the suspect’s family.

But after [the draft’s release], there was really potent criticism both from people inside China and outside China, the final law was revised and first to limit use to “especially” serious bribery and second to cabin the initially sweeping lack of notice provisions by changing it to “except where notification cannot be processed that there should be notification to the family.” But critics continue to raise concerns that notice might not include the actual location of the suspect or other crucial information.

With respect to detention, there is a provision that provides that a detainee’s family needs to be notified within twenty-four hours unless again notification cannot be processed or where the detainee is involved in crimes endangering state security or crimes of terrorist activities, and notification may hinder the investigation. What these exceptions to the standard rule of family notification actually mean in practice, this will only be apparent over time.

EL: Just to follow up and to clarify a little bit, can anyone be placed under residential surveillance for any crime? How do they distinguish or is it just left totally in the prosecutor and public security bureau’s hands?

ML: It is limited to certain crimes and types of suspects by law but I can’t verify how it will be used in practice and some of those categories are quite broad. Other [provisions] are more direct saying that for certain categories of people for whom residential surveillance can be used when the conditions for arrest have been satisfied, such as people who are seriously ill or pregnant women…so I’d currently be eligible for residential surveillance. If you see residential surveillance as an alternative to locking someone up in what could be a very harsh jail-type setting, it comes across as a positive thing. If you’re pregnant or breast feeding, to have you in a comfortable place, albeit secured and you’re being watched. But if it becomes a sweeping way to have suspects being held for long extended periods of time, it starts to look a little less rosy.

EL: When exactly are the police or the prosecutor allowed to put someone under residential surveillance? Do they have to be arrested? Or can it be before that, during the interrogation stage?

EL: When exactly are the police or the prosecutor allowed to put someone under residential surveillance? Do they have to be arrested? Or can it be before that, during the interrogation stage?

ML: It can be used both for suspects during the investigation stage or for people who have been formally arrested. The term “arrest” [daibu – 逮捕] in China often occurs much later than how we colloquially think of arrests in the U.S. People in China can be in custody without being formally arrested. Bottom line is its scope is quiet broad as far as when it can be invoked in the criminal process.

EL: We do know there are time limits to detention but is there a time limit under which one can no longer be under residential surveillance or is it not clear at this stage?

ML: The law provides that the period for residential surveillance shall not exceed six months. Again, only time will tell whether this time limit is followed in practice. It’s unclear at this point whether there might be some ways to reset the clock, some new charges, how this might be massaged, but the law does at least provide a clear time limit that might give lawyers and families something to work worth.

EL: When the draft first came out back in 2011, I think the majority of China’s legal academics were rather alarmed by the legalization of residential surveillance. But there were a few that did argue that in a way it was a positive development, that residential surveillance was happening anyway and now at least there are rules governing the process that must be followed. What do you think of that argument, do you think there is any validity to that?

ML: I agree that there is something to be said for honesty instead of simply codifying an ideal system that has no basis in reality. That said, I personally am worried that the procedural limits on residential surveillance and other liberty-depriving mechanisms will not be strictly enforced; they’ll take the power that the law gives them without the restrictions. As implementation proceeds, a question to watch is whether these new provisions merely expand the tools available to police without providing any concrete safeguards against their unfettered use.

Training on the New CPL

EL: I think that brings us to an issue that I think has been floating under the surface during this whole interview which is that at least on paper there seems to be better protect the rights of criminal suspects. But it seems like a lot of the initiative in protecting criminal suspects has to come from the police and the prosecutor’s offices. Since the new law was passed in March 2012, do you know if there have been any training for the police and/or the prosecutors to prepare them for January 1, 2013, implementation, when it takes effect?

ML: As was done after release of the 2010 evidence rules and all sorts of prior declarations, there are reports of course that police, prosecutors, and judges are undergoing various trainings in preparation for the new law taking effect. Of course we are also waiting for this guidance that should come not only from the Supreme People’s Court but similarly guidance from [1] the Supreme People’s Procuratorate to the prosecutors, and [2] the Ministry of Public Security, to the police, some of which could be public some of which might not.

Even with the new CPL, it is important to emphasize that it does not address the full criminal process. The law spans the life of the case from its initial filing through appeals and execution of punishments. The law does not comprehensively address procedures for the earliest handling of a case by the police prior to involvement by the procuratorate. This entirely police-dominated phase remains the least understood aspect of China’s criminal justice system and, arguably, the most crucial. So there is still a lot we don’t know and that is important to recognize.

EL: Right, right. That is very interesting that you bring that up, that there are no changes with what’s going on with the police and we don’t know. But in that regard, what about with the criminal defense bar. Has there been any efforts for the criminal defense bar to better learn the new law and to perhaps strategize how to use it to better protect their clients?

ML: There are many dedicated, and even fearless, defense lawyers in China who are hard at work to figure out how best to use the new law. As is

the case currently, a lawyer’s good relations with the local authorities handling a case is what’s truly critical when advocating for a client.

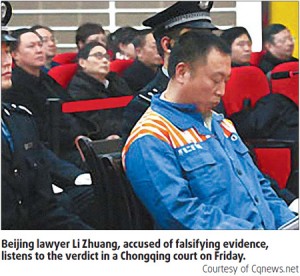

I commend anyone who takes on the difficult task of being a defense lawyer in China. The long complaint of the defense bar is that they have the “Three Difficulties”— the difficulty in meeting with clients, the difficulty in getting access to the prosecution’s case files, and the difficulty in carrying out investigation and collecting evidence. But lawyers have been recently expanding this critique to the “Ten Difficulties”— you take the original three and then we add on the difficulties of obtaining bail, getting witnesses to appear, obtaining a hearing for an appellate trial, pleading innocent, participating in the process of death penalty review, abolishing the criminal law that criminalizes when lawyers specifically encourages witnesses to change their testimony, and also the difficulties in proving that evidence was illegally obtained.

There are so many barriers and perhaps this new law will diminish those barriers, but I think there is a sense of being beleaguered amongst the defense bar right now.

EL: What’s interesting too is what you mentioned before, that most criminal defendants aren’t actually represented in court or in any part of the proceedings. Has there been anything done to guarantee that those defendants without lawyers, which is probably the majority, know about their rights? Have there been any public education campaigns? At the very least, does China have any TV shows like Law & Order? I feel like everybody in the United States knows their rights through Law & Order.

ML: Even more interesting is that people in China watch our TV shows. When I was over there earlier this summer I got a number of questions about whether plot lines on The Good Wife were actually reflecting what happens in courtrooms, and I don’t watch the show so I was at a bit of a loss. But obviously that’s hit the DVD stands as well.

The revised CPL mentions an increased role for legal aid and that raises hopes that the revisions could usher in some meaningful changes, though I am again withholding much in the way of praise until we see changes in practice.

I think the bigger force for change will be weibo and other technologies that can quickly and broadly spread word of cases like Zhao Zuohai’s where there has been a clear miscarriage of justice. That would have been swept under the rug a matter of years ago but, once that was out there in the public sphere and spread like wildfire, there was no way to put that toothpaste back in the tube. So really the most effective push for real change will likely come from large-scale public outcries based on real cases rather than government slogans.

EL: Right, and that Zuo….what’s his name?

ML: Zhao Zuohai.

EL: Zhao Zuohai. A lot of people think that’s what brought about the 2010 exclusionary rules.

ML: And there are other cases that continue to come out, and I think that when you put a real face on the injustice it does a lot more than having slogans painted on a bulletin board.

EL: Well, okay. There is still a lot to talk about with the new CPL and I think you’re right, a lot of it we won’t really know what happens until it is actually implemented and starts going into use, but I do want to thank you very much Prof. Lewis for sitting down with us today and explaining a lot of the new developments with China’s new Criminal Procedure Law. Thank you.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email