A Very Unmerry Christmas from China

In happier times, Wang Quanzhang, his wife Li Wenzu and their son.

This Christmas night, as many across the Western world celebrate this holiday of peace, Wang Quanzhang, a Chinese human rights lawyer, will be jolted awake from his jail cell, rushed to get dressed, and paraded into a courtroom in Tianjin for a criminal trial whose verdict was likely already determined.

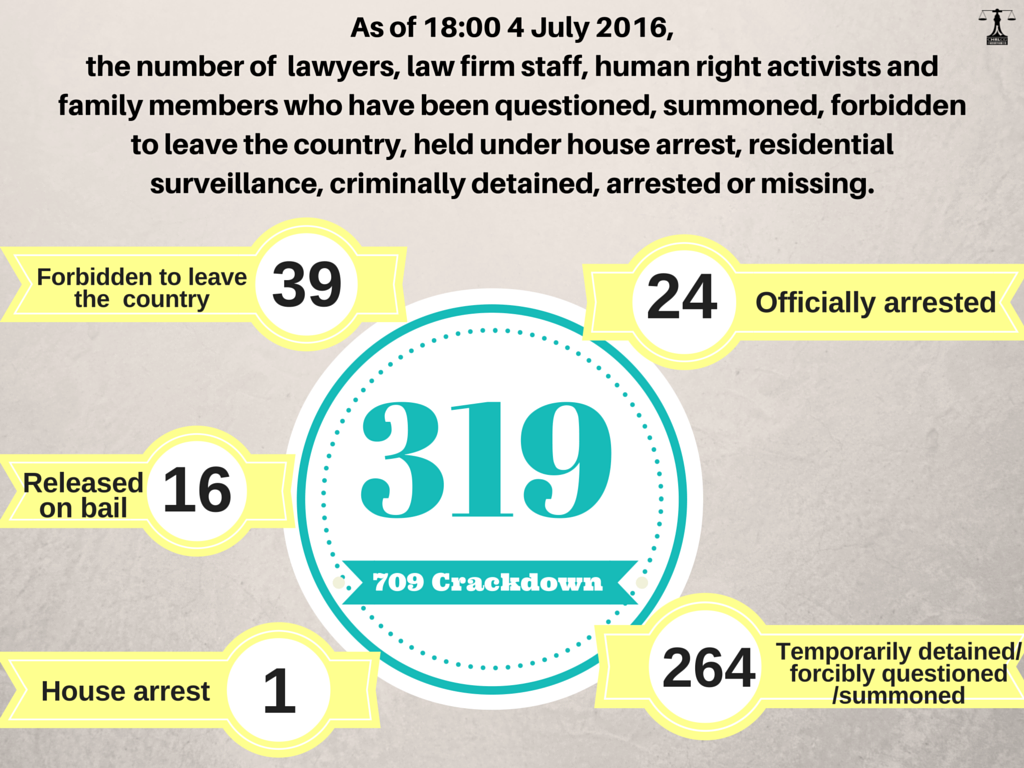

Wang is the final victim of the Chinese government’s nation-wide crackdown on human rights advocates, a crackdown that happened three and a half years ago in July 2015. While most of the other victims of the crackdown have been dealt with, Wang has been held incommunicado – in violation of Chinese law – for over three years. Unable to see his lawyers or his wife, news of Wang’s well-being has been limited, with news reports occasionally confirming that he is in fact still alive.

But on Christmas Eve, his wife, Li Wenzu, tweeted that she was just informed that Wang would go on trial on December 26. Make no mistake, the Chinese government’s choice of the day after Christmas for Wang’s trial was intentional. And does not bode well for Wang. Knowing that much of the Western world shuts down between Christmas and New Year’s, the Chinese government has used that time to sentence some of its most famous advocates to harsh – and unjustified – prison sentences. As RFI has pointed out, Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, who eventually died in a Chinese prison, was sentenced to 11 years on Christmas Day 2009. And on December 26 of last year, human rights advocate Wu Gan, another victim of the Chinese government’s 2015 crackdown, was given an eight-year sentence.

For Wednesday, expect another severe sentence for Wang Quanzhang who has been charged with the serious crime of subverting state power. Not only has Wang refused to “confess” in exchange for leniency and agreeably participate in a show trial, the Chinese government has vilified Wang by name in the press, including naming him as a ringleader. It also has alleged that because of the alleged influence of “foreign forces,” specifically the use of foreign NGO funds, these lawyers, including Wang, are national security risks. And don’t expect the passage of time to soften the government’s view of Wang, especially as China’s economy slows down, threatening the current regime’s stability and power.

For Wednesday, expect another severe sentence for Wang Quanzhang who has been charged with the serious crime of subverting state power. Not only has Wang refused to “confess” in exchange for leniency and agreeably participate in a show trial, the Chinese government has vilified Wang by name in the press, including naming him as a ringleader. It also has alleged that because of the alleged influence of “foreign forces,” specifically the use of foreign NGO funds, these lawyers, including Wang, are national security risks. And don’t expect the passage of time to soften the government’s view of Wang, especially as China’s economy slows down, threatening the current regime’s stability and power.

The crime of subversion of state power – Article 105 of the Chinese Criminal Law – carries some of the most severe penalties short of capital punishment. Much is determined on the role of the individual in the subversion. A ringleader must receive a minimum of 10 years; the maximum sentence is whatever the court – or in this case the Chinese government – wants. For those who actively participated in the subversion but were not ringleaders, the sentence can be anywhere from between three and 10 years; and those who were mere “participants”, the sentence cannot be more than three years and can be as minimal as controlled release or the deprivation of political rights. For those who incite subversion (as opposed to actively participate in it), ringleaders shall receive no less than five years and all others no more than five years.

Li Wenzu, Wang Quanzhang’s wife, shaves her head in protest of the three and a half year detention of her husband.

The Chinese government has failed to make the indictment public and likely Wang’s wife – who has been protesting her husband’s detention including publicly shaving her head last week – has not seen it either. So it is unclear under what portion of Article 105 the Chinese government will seek to punish Wang. But given the fact that it has already claimed that Wang was a “ringleader,” have held him for over three years with limited access to a lawyer, and is setting this trial for the day after Christmas, expect a severe sentence, likely in the double-digits. But for Wang, his wife and five-year-old son’s sake, and for China’s future, we hope we are very, very wrong.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email