One Love: How Foreign NGOs & Governments Should Respond to China’s Draft Foreign NGO Law

In Part 1 of this three-part series, we analyzed how the draft law will restrict foreign NGOs in China, In Part 2, we examined how the spirit of the draft law is already being felt. For Part 1, click here; for Part 2, click here.

More than a week has passed since the Chinese government published its draft Foreign NGO Management Law. But yet the world largely remains silent – no word publicly from the foreign NGO community in China, the foreign universities that do work in the Mainland or the foreign governments who often fund NGOs working there. But in light of the draft law’s potentially disastrous effects, is silence really a good strategy?

More than a week has passed since the Chinese government published its draft Foreign NGO Management Law. But yet the world largely remains silent – no word publicly from the foreign NGO community in China, the foreign universities that do work in the Mainland or the foreign governments who often fund NGOs working there. But in light of the draft law’s potentially disastrous effects, is silence really a good strategy?

We’re One, But We’re Not the Same? Which Foreign NGOs Will Be Covered by the Draft Law

The draft Foreign NGO Management Law is anything but an example of clarity. But there are two things we know for sure from the current version: foreign NGOs that have an office in China are covered and foreign NGOs without offices in China that seek to conduct activities there are also covered. (Art. 6). We also know that the ultimate authority over all foreign NGOs, whether setting up an office in China or merely conducting activities there, is the Public Security Bureau (PSB) (Arts. 7, 12, 20 & 47).

As China Law Translate notes in its Cheat Sheet for Understanding the Foreign NGO Law, what is a foreign NGO is defined expansively as any “not-for-profit, non-governmental social organization.” (Art. 2). Such a broad definition can “include universities, international professional associations and interest groups, artistic groups and athletic associations” in addition to what we view as traditional NGOs like the Red Cross.

Similarly, the term “activity” is left undefined, allowing it to encompass anything. However, even those foreign NGOs without an office in China will be required to establish a relationship with a Chinese partner in order to obtain a temporary activity permit to perform any work in China. (Arts. 18-20). The entire process can take 60 days or more, depending how easy it is to establish a relationship with a Chinese partner. (Art. 20 & 22). Will Doctors Without Borders have to apply for a temporary activity permit before responding to a medical emergency in China? Under the current, vague draft, yes.

Universities are also covered under the current draft law. It is that fact that has alarmed many Chinese scholars who realize that academic exchanges will be negatively impacted by the current, vague draft.

Ultimately, under the proposed draft Foreign NGO Management Law these terms will all be defined by the PSB. And changed as the PSB sees politically expedient.

Well We Hurt Each Other Then We Do it Again? Universities and Foreign NGOs Need to Stand Together

As Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher highlight in their report Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire, governments seeking to limit foreign NGOs are “skillful at dividing and conquering the international aid community.” Is the Chinese government hoping that some foreign aid organizations will not oppose the draft law, eager to curry favor so that they can continue their work in China?

As Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher highlight in their report Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire, governments seeking to limit foreign NGOs are “skillful at dividing and conquering the international aid community.” Is the Chinese government hoping that some foreign aid organizations will not oppose the draft law, eager to curry favor so that they can continue their work in China?

But with the amorphous definition of a foreign NGO under the draft law, that is a dangerous strategy for any foreign NGO with either offices in China or that just conducts activities there. Almost all NGOs are covered under the current definition and that is why it is important that the foreign NGO community, including universities, stand as one in commenting and opposing the current draft.

Universities and major non-profits have an even greater responsibility to publicly comment on the proposed draft law. In the current environment in China, not all foreign NGOs are equal. The Rights Practice, which just had one of its staff members deported from China, likely does not have the same credibility before the current Chinese regime as the Gates Foundation, NRDC, or Save the Children, which in January hosted President Xi Jinping at one of its spaces in Yunnan. These are organizations that have long supported Chinese civil society actors in benefiting the Chinese people. It is important that these major NGOs continue to support civil society in its entirety, not just those sectors that the PSB presently approves. Further, these major NGO’s do not know when their own work will imperil them with the PSB and thus, could find themselves subject to the harsh, vague provisions of the current draft Foreign NGO Management Law. Five years ago, who would have thought that a group of individuals with hepatitis seeking to end discrimination would be considered a threat. But that is where Yirenping finds itself today.

U.S. and European universities have the best footing to comment on the draft Foreign NGO Management Law.  These universities likely have thousands of academic exchanges – covering law, science, engineering, medicine – exchanges where the Chinese university likely derives tremendous benefit. Even with the growing police state, the Chinese government probably does not want to risk losing even some of these beneficial relationships.

These universities likely have thousands of academic exchanges – covering law, science, engineering, medicine – exchanges where the Chinese university likely derives tremendous benefit. Even with the growing police state, the Chinese government probably does not want to risk losing even some of these beneficial relationships.

It is imperative that these major foreign NGOs and universities stand with those foreign NGOs that are the current target of the law and openly comment on the draft law. Is the Gates Foundation really going to be kicked out of China? Is UC Berkeley’s Engineering School?

You Give Me Nothing Now It’s All I Got: Where is the White House on All of This?

Last Friday, U.S. President Barack Obama recognized that if the we don’t write the rules, China will. Unfortunately, for the non-profit world, Obama limited that rule-writing to trade issues and support for his Trans-Pacific Partnership.

It is time that the White House recognize that with China, there are more rules out there than those that directly govern trade. The Obama Administration has allowed too many non-trade issues – U.S. journalist visas, now foreign NGOs – to receive scant attention as a U.S.-China policy matter. With the U.S. abandoning these issues, China is writing the rules in these important areas, and these will be rules that other countries will copy.

But the Administration is not without recourse. It too can submit comments on the draft law and should. When U.S. technology companies appeared to be negatively impacted by China’s draft Counter-Terrorism Law published late last year, Obama made his displeasure publicly known. There is no reason to why he cannot do the same with the draft Foreign NGO Management Law. And comments from the Administration can no longer be relegated to a State Department spokesperson. If there is anything to be learned from the handling of the U.S. journalist visa issue with the Chinese government, a State Department spokesperson is not going to cut it when dealing with the world’s second largest economy. It wasn’t until Vice President Joseph Biden visited China in December 2013 and publicly raised the U.S. journalist visa hold-up, did China start taking the issue seriously. Soon after, U.S. journalists’ visas were renewed.

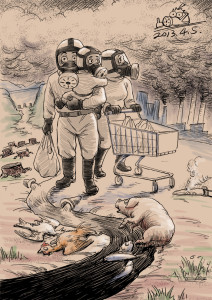

Although the Obama Administration should oppose the draft Foreign NGO Management Law on the grounds that its radical clampdown on civil society is anathema to the interest of the Chinese people, opposition can also be tied to trade. Chinese domestic civil society groups often deal with the flipside of free trade – environmental degradation, workplace justice, product safety. And these are issues that are increasingly coming to our shores: air pollution from China now reaches California; unsafe products made in China are sold in the United States. Chinese NGOs seek to enforce environmental regulation and product safety laws. Although their goal is to protect the Chinese people from the harms of unregulated capitalism, a side benefit of Chinese NGOs’ success accrues to the American people. California becomes cleaner and U.S. citizens fear Chinese goods less. But if the draft Foreign NGO Management Law is passed in its current form, an important lifeline of Chinese civil society – the foreign NGO – will potentially be cut off. To ensure a balanced trade relationship with China, the Obama Administration must comment on the current draft law. One opportunity is right around the corner: the annual U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue to be held this June in Washington, D.C.. The draft Foreign NGO Management Law, and the important role civil society plays in a free trade world should be on the agenda.

Finally, the increasingly unbridled power of the public security apparatus, evident in the draft Foreign NGO Management Law as well as the draft National Security Law, which was published only days after the NGO law, should frighten any entity that deals with China – be it a not-for-profit, a business or the U.S. government. To ignore that development and to believe that the supremacy of the PSB is somehow limited to civil society issues is to do so at the peril of all of the United States’ interests in Asia, including business and military interests.

Like foreign NGOs and universities, the United States government has the opportunity to comment on the draft Foreign NGO Management Law and should do so. Ironically, the comment period closes on June 4, 2015, the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

Like foreign NGOs and universities, the United States government has the opportunity to comment on the draft Foreign NGO Management Law and should do so. Ironically, the comment period closes on June 4, 2015, the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

Would you like to make your comment public on China Law & Policy? Please email us at info@chinalawandpolicy.com with your agency’s comment and we will publish it (assuming it is related to the topic and is family-friendly).

***************************************************************************

This concludes China Law & Policy’s three-part series on China’s draft Foreign NGO Management Law. To read Part I where we analyzed how the draft law will restrict foreign NGOs in China, click here. To read Part 2 where we examined how the spirit of the draft law is already being felt, click here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email