Forced Departure of American Journalist Megha Rajagopalan – Is it Really Not About Xinjiang?

***Correction – After this post was published, a reader with experience on Chinese visa issues informed China Law & Policy that it isn’t always that a news outlet cannot establish a permanent office because of economic costs or means, but also because the Chinese government will not allow certain news outlets to establish a permanent office, thus preventing those reporters the ability to obtain the J-1 visa. We have corrected the post to reflect this important difference and thank the person who informed us. EML, Sept. 10, 2018***

Buzzfeed’s Former Beijing Bureau Chief, Megha Rajagopalan

Every three years, the Chinese government has effectively expelled a foreign journalist from China. It started with Melissa Chan, an American journalist working for Al Jazeera, in 2012. In 2015, it was Ursula Gauthier, a French journalist for L’Obs. And last month it was Megha Rajagopalan, the Beijing Bureau chief of the online news magazine Buzzfeed.

With each expulsion of a foreign journalist comes speculation as to why. Why did the Chinese authorities fail to renew a visa or cancel a press card. The Chinese government hardly ever explains its reasons, citing that such failure to renew a visa was “in accordance with law.” But no law or regulation is ever cited, let alone a specific provision. As a result, most outside of China view the Chinese government’s decision having more to do with the reporter’s coverage of China than with any violated regulation. With Gauthier, the Chinese government was more explicit about its decision to cancel her press card, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) criticizing Gauthier by name because of her scathing editorial on the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uighurs, a Muslim ethnic minority, in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of China.

Here, there can be little doubt that it was Rajagopalan’s reporting that resulted in her effective expulsion from China. Under the law, MOFA clearly could have renewed Rajagopalan’s short-term journalist visa. For some reason, it chose not to

Rajagopalan’s Reporting on Xinjiang – Why Is the Chinese Government So Sensitive About This?

Rajagopalan’s Reporting on Xinjiang – Why Is the Chinese Government So Sensitive About This?

Like Gauthier, Rajagopalan had done some hard-hitting reporting on the Uighers in Xinjiang, with an October 2017 article exposing the Chinese government’s increased surveillance and its mass detention of Uighurs for no other reason than being Uighur. Reporting from Xinjiang, Rajagopalan’s article was one of the first to uncover the Chinese government’s frightening oppression of Uighurs. It also won her the Human Rights Press Awards’ Best Features Article (English) for that year. In July 2018, Rajagopalan followed up her ground-breaking piece with another explosive article that brought to light the Chinese government’s pressure tactics on Uighurs abroad, including threats to send their Xinjiang-based family to internment camps if they do not spy on other Uighurs.

Xinjiang has long been a sensitive area for the Chinese government, fearing that the Muslim Uighurs could launch a successful separatist movement. As a result, for over a decade, the Chinese government has instituted a national policy to “Go West,” encouraging ethnically Han Chinese to move to Xinjiang to develop this resource-rich area. With the Go West policy, Xinjiang’s population has changed dramatically, with a current Han population of 40%, compared to 6% in 1949. And with the increase in the Han population has come a decrease in the Uighur’s political clout and self-governance since Chinese Communist Party membership usually means giving up religion. Few of the ethnically Muslim Uighurs are atheists and hence, unable to join the Party, and thus unable to effect change in their own region. For example, when, in 2009, the Chinese government decided to destroy much of the the old city of Kashgar, a city that stood for centuries and was perhaps the most Uighur area of all of Xinjiang, the Uighurs were unable to stop it. Needless to say, such loss of power over their own destinies and the attempted destruction of their own cultural identity has not produced a population satisfied with Chinese rule.

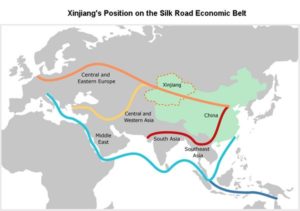

Some of the routes on China’s One Belt, One Road

And Xinjiang’s importance to the Chinese government has only increased in recent years as Xinjiang is central to the success of China’s “One Belt, One Road” policy. Launched in 2013, One Belt, One Road is China’s very serious and well-funded attempt to exert economic influence globally. Xinjiang is the key land route to Central Asia and Europe, making it even more crucial that the Chinese government subdues the Uighur population. To do so, in 2015, the Chinese government passed two national laws that had an disparate, negative effect on the Uighurs of Xinjiang: the broadly-worded National Security Law, that equated religious “extremism” with terrorism, and the Counter-Terrorism Law, which gave security forces significant powers to prohibit “extremism.” Xinjiang was the first province to issue local regulations to carry out the precepts of the Counter-Terrorism law, including mandating governmental “aid and education” for those individuals who, while not convicted of any crimes, were induced into participating in terrorism or extremism, seemingly laying the groundwork for the mass detentions currently occurring. (See Xinjiang Implementing Regs of the Counter-Terrorism Law, Art. 38) And Rajagopalan’s article was one of the first to show that Uighurs were in fact being massively surveilled and detained in re-education internment camps without ever being tried – let alone convicted – of any crime. Instead it was the simple practice of their religion that the government viewed as “extremism.”

Since Rajagopalan’s October 2017 article, both by the United States Department of State and the United Nations estimate that close to a million Uighurs have been sent to these internment camps without any trial, all for the purpose of stamping out the Uighur identity. And there appears to be no end in sight with satellite images showing the rapid building of what looks like even more internment camps.

Chinese police officer stands guard outside a mosque in Xinjiang.

As more and more information began to emerge in the international media about the depth of the Chinese government’s whole-scale human rights violations against Uighurs, and as foreign governments and international bodies began to take notice and advocate sanctions against China, Rajagopalan’s visa was almost up and the Chinese government was in the midst of determining whether to renew it. In May 2018, MOFA, the oversight agency of foreign journalists, informed Buzzfeed Rajagopalan’s journalist visa would not be renewed, forcing Rajagopalan to leave China as soon as it expired.

When questioned at an August 23, 2018 press conference, MOFA spokesperson Lu Wei stated that Rajagopalan’s visa issue was handled “in accordance with law and regulation” and, in his remarks, made a distinction, without explaining the significance, between Rajagopalan’s visa – a short-term journalist visa, known as a J-2 visa – and a resident foreign reporter’s visa, known as a J-1 visa.

Are J-2 Visa’s Non-Renewable Under Chinese Law?

Unlike the United States, where there is only one type of journalist visa, Chinese law distinguishes between two types of journalist visas, the J-1 and the J-2. The J-1 visa can only be issued to journalists whose news agency has a permanent office in China (See Regulations on the Exit-Entry of Foreign Administration of Foreign Nationals (“Exit-Entry Regulations”), Article 6(5)). Because of the “permanent office” requirement, J-1 visas are increasingly issued to only more traditional outlets; think the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian, etc. J-1 visas also confers residency status, and J-1 visa holders must also apply for a Press Card from MOFA within 7 business days of their arrival in China. (See Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on News Coverage by Permanent Offices of Foreign Media Organizations and Foreign Journalists (“Foreign Media Regulations”), Article 10).

Unlike the United States, where there is only one type of journalist visa, Chinese law distinguishes between two types of journalist visas, the J-1 and the J-2. The J-1 visa can only be issued to journalists whose news agency has a permanent office in China (See Regulations on the Exit-Entry of Foreign Administration of Foreign Nationals (“Exit-Entry Regulations”), Article 6(5)). Because of the “permanent office” requirement, J-1 visas are increasingly issued to only more traditional outlets; think the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian, etc. J-1 visas also confers residency status, and J-1 visa holders must also apply for a Press Card from MOFA within 7 business days of their arrival in China. (See Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on News Coverage by Permanent Offices of Foreign Media Organizations and Foreign Journalists (“Foreign Media Regulations”), Article 10).

J-2 visas are issued to journalists who come to China for short-term reporting and there is no permanent office requirement. (Exit-Entry Regulations, Article 6(5).) Traditionally, those are journalists coming to do a one-off story; for example, when a New York Newsday reporter travels to cover the U.S. President’s visit to China, or the Des Moines Register sends a reporter to cover the pork market in China. J-2 visas are limited to six months (Foreign Media Regulations, Article 2) and J-2 journalists do not obtain a Press Card.

But increasingly, news agencies are seeking to send long-term reporters to China without establishing a permanent office. This is especially true of online outlets like the Huffington Post and Buzzfeed, who, according to a source with knowledge of China’s visa issues, the Chinese government will not permit to set up a permanent offices. or any agency that just doesn’t have the deep pockets of a Wall Street Journal or a New York Times. But because they do not have a permanent office, Thus, their China-based reporters cannot obtain a J-1 visa. Instead, the Chinese government has been providing these reporters with a J-2 visa with the understanding that the visa will be renewed when the initial term is over. According to the New York Times, this was the deal that Buzzfeed worked out with the Chinese government prior to Rajagopalan’s arrival –a six month J-2 visa renewable upon its expiration. But when Rajagopalan’s six months were up, MOFA failed to renew her J-2 visa.

MOFA’s response to the question about the failure to renew Rajagopalan’s visa – that she was not a resident foreign reporter – seems to imply that the law does not permit the renewal of J-2 visas. But this is not true. Article 29 of China’s Exit-Entry Administration Law clearly contemplates the renewal of any short-term visa. Article 29 lays out the procedures by which the holder can apply for an extension and the only limitation being that the renewed visa cannot be for a longer length of time than the original visa.

Al Jazeera journalist, Melissa Chan, back when she could report from China

In fact, MOFA has renewed J-2 visas in similar situations. For two years, Matt Sheehan was the Huffington Post’s China-based reporter, meaning that his J-2, short-term visa must have been renewed every six months. Similarly, Melissa Chan had three J-2 visas, repeatedly renewed until the Chinese government refused to renew her visa for a fourth time.

MOFA had the authority to renew Rajagopalan’s J-2 visa, it just decided not to. And Rajagopalan’s reporting on Xinjiang was the catalyst that has led to the current international attention to Xinjiang, including the United Nations’ Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s public rebuke of the Chinese government’s practices in Xinjiang. In July, the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) held a powerful hearing condemning China’s human rights violations in Xinjiang and calling for the use of the Magnitsky Act against officials involved with Xinjiang.

Going to market in the police state of Xinjiang

Every day there are more and more articles exposing the internment of millions and the efforts to eliminate the Uighur culture. The international heat is on about the Chinese government’s human rights violations in Xinjiang. And the Chinese government’s failure to renew Rajagopalan’s visa was not just retribution against her. Likely it was intended as a teaching lesson to other journalists – report on this and we might fail to renew your visa too. Fortunately, no one has taken the cue and powerful reporting continues. What will be the test comes this December, when all resident foreign reporters go through the annual rite of renewing their press cards and J-1 visas. On some level, Rajagopalan, with her short-term J-2 visa, was low-hanging fruit. Will the Chinese government conveniently lose paper work of resident foreign journalists, forcing them to leave the country while they wait for their paperwork to be found? Or will press cards be canceled? Or even more terrifyingly, will the Chinese government completely close off all access to Xinjiang?

Make no mistake, Rajagopalan was only the start. Xinjiang – and the Chinese government’s desire to eradicate a strong Uighur identity – is too important for the Chinese government not to ratchet up its game.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

Under Article 4 of the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA does not have to criminally prosecute Gauthier for a crime or even give her any form of due process (such as appealing the decision). Under the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA is the judge and jury of violations of the Regulations and with Article 4’s broad strokes, it is easy to find a foreign journalist in contempt of the Regulations. So for those foreign journalists who thought the worst was over in terms of the annual visa renewal process, think again. While

Under Article 4 of the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA does not have to criminally prosecute Gauthier for a crime or even give her any form of due process (such as appealing the decision). Under the Foreign Media Regs, MOFA is the judge and jury of violations of the Regulations and with Article 4’s broad strokes, it is easy to find a foreign journalist in contempt of the Regulations. So for those foreign journalists who thought the worst was over in terms of the annual visa renewal process, think again. While