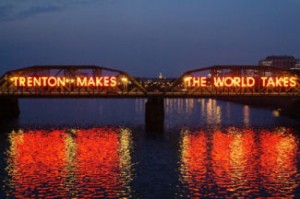

I used to think I was the only one who noticed the huge, weird, angry sign “Trenton Makes the World Takes” plastered on the Delaware Bridge just outside the New Jersey city of Trenton. So imagine my surprise when this slogan was featured in Commerce Secretary Gary Locke’s speech about U.S.-China relations before the U.S.-China Business Council (USCBC) on Thursday. For Locke, the manufacturing center of Trenton during the early 20th Century is China today; it’s China that now makes and the world takes.

I used to think I was the only one who noticed the huge, weird, angry sign “Trenton Makes the World Takes” plastered on the Delaware Bridge just outside the New Jersey city of Trenton. So imagine my surprise when this slogan was featured in Commerce Secretary Gary Locke’s speech about U.S.-China relations before the U.S.-China Business Council (USCBC) on Thursday. For Locke, the manufacturing center of Trenton during the early 20th Century is China today; it’s China that now makes and the world takes.

But the status quo must change Locke argued. While noting some successful U.S.-China commercial relations, Locke raised the issue of market access in China, particularly in light of China’s indigenous innovation policies and its lax protection of intellectual property (which makes one wonder why didn’t he continue to play with the Trenton theme and say “China makes AND takes”; that would have elicited laughs from the USCBC for sure), Between Locke’s speech, reprinted below, and Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner’s speech Wednesday, there is some serious saber-rattling coming from the American delegation in preparation of President Hu Jintao’s State visit next week.

Commerce Secretary Gary Locke Delivers Policy Speech

on U.S.-China Commercial Relations

Thank you John, for that kind introduction. And thank you for having me here today.

We are today less than a week away from an important State visit by Chinese President Hu Jintao.

More than two decades ago, on my first trip to mainland China, I could not imagine that the U.S.-China relationship would eventually become so consequential.

Nor could I have imagined a scene like we witnessed a few days ago: Defense Secretary Gates joining together with his Chinese counterpart to stress the need for stronger military ties between China and the United States.

In 1989, I came in from Shanghai’s airport on a rickety, Russian-made bus, and stepped into that city’s dimly lit streets into a world very different than the one I left in the U.S.

There were swarms of bicycles – young men with their dates balanced on handlebars, grandparents pedaling to the market, boys and girls with white-knuckle grips on their parents’ shoulders. Bikes everywhere.

Shanghai then was a gritty, industrial city filled with low-rise buildings.

There were no skyscrapers. Few cars.

There was little sign of what was to come.

Today, Shanghai’s skyline is dotted by more than 400 skyscrapers. Go to the Shanghai World Financial Center – one of the tallest buildings in the world – and you can stay at a Park Hyatt Hotel with a lobby on the 79th floor.

Those bike paths I saw on my first visit have been replaced by elevated freeways shuttling people and commerce at a frenetic pace.

To see it is to be awed, and I am every time I go back to China.

The explosive growth in places like Shanghai has helped lift almost 200 million people out of poverty. In the years ahead, hundreds of millions more Chinese citizens will join the middle class.

The United States welcomes this growth, because it’s good for the people of China; it’s good for the global economy; and it’s important for U.S. companies who offer world-class products and service, products and services that can improve the quality of life for the Chinese, while providing jobs for American workers back home.

With the U.S.-China Business Council’s help, this has become perhaps the most important bilateral trading relationship in the world.

China is the top destination for American exports, behind just Canada and Mexico. And America is the number one national market for Chinese exports.

In the past 20 years, U.S. exports to China have increased by a factor of 12; imports from China have increased more than 30-fold.

However, we are at a turning point in the U.S.-China economic partnership. Last year, China became the second largest economy in the world. And the policies and practices that have shaped our relations over the past few decades will not suffice over the next few decades.

So today, I’d like to talk a bit about how we can move forward and ensure that we can unlock the full potential of the U.S.-China commercial relationship in the early 21st century.

The gross trade imbalances between our countries are a good place to start, because they have the potential to threaten global stability and prosperity.

And I think a great illustration of that can be found in, of all places, Trenton, New Jersey.

Many of you have likely taken Amtrak up to New York, and when you pass by the Delaware River in New Jersey, you see that famous sign: Trenton Makes and the World Takes.

Well, replace Trenton with China, and you have a simplistic, but pretty accurate description of the global economy over the last few decades.

China and the United States benefited tremendously from this arrangement in recent years.

American consumers got an impressive array of low-cost goods. And in its transition into one of the world’s top exporters, China was able to lift millions of its citizens into a fast-growing middle class.

But it’s not sustainable. The debt-fueled consumption binge in developed countries like America is over.

And countries like China are beginning to realize that there are limits to purely export-driven growth.

That’s why we need a more equitable commercial relationship. And it is within our reach.

The United States is doing its part to facilitate global adjustments by increasing private savings and exports, as well as taking steps to bring down its long-term fiscal deficits to a sustainable level.

And the Chinese leadership is making the rebalancing of its economy one of the cornerstones of its forthcoming five-year plan.

China is aiming to promote domestic consumption through a variety of measures, such as boosting the minimum wage for its workers and building an improved social safety net. Changes like these will hasten the rise of a middle class that wants the same cars, appliances, fashion, medical care and other amenities that have long been enjoyed by consumers in the Western world.

The Chinese government is also putting an intensive focus on strategic emerging industries, with more high-value work in areas like healthcare, energy and high technology.

And the Chinese have signaled that they want foreign businesses to help develop these sectors by entering joint ventures and by conducting more research and development in China.

This is assistance that U.S. companies are eager to provide, so long as China deals meaningfully with concerns about intellectual property protection, as well as a variety of other issues I will talk about later.

Such cooperative projects can serve as the foundation for a stronger economic relationship between China and the U.S.

But China’s long-term success at addressing the concerns of international businesses will help determine whether it realizes its economic vision – a vision in which China is a leader in innovation and a producer of higher-value goods and services.

Here’s the good news: we are already seeing examples of just how this future could play out, as our businesses and our governments collaborate to tackle some of the world’s greatest challenges.

Just look at what’s happening with the new Energy Cooperation Program that Secretary Chu and I announced while in China in October 2009 to promote more collaboration between Chinese and American companies on energy issues. One of the founding corporate members of the program, Boeing, is partnering with Air China and Petro China to research a new generation of aviation biofuels that don’t rely on food crops.

If this venture is successful, it could reduce the carbon footprint of airplane travel, and avoid the negative impact that other biofuels have on the global food supply.

Or look at what’s happening with Duke Energy, one of America’s leading utilities, which has signed an agreement for joint research with China’s largest energy company, Huaneng, and with the Chinese government’s Thermal Power Research Institute.

Today, there are scientists and researchers shuttling between the companies and the research institute, working to develop cutting-edge solutions for cleaner-burning coal and carbon sequestration.

The Chinese and American governments are also working together on a variety of transportation issues, including how to spur the deployment of more high-speed rail. China has embraced high-speed rail and has developed its infrastructure at a tremendous rate. Starting from scratch, China has constructed and put into service over 4,000 miles of high-speed routes in the last decade – making China’s the longest high-speed rail network in the world.

In meetings last year, officials and experts from the Department of Transportation and China’s Railway Ministry met in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to share information on the development of high-speed rail standards. And at the state level, the Chinese government has signed cooperation agreements with the State of California on its high-speed rail project to link Anaheim and San Francisco.

There is, however, a sobering side to U.S.-China commercial relations: For every story like Duke Energy’s or Boeing’s, there are many more that are never written.

When I talk to business leaders across America, they continue to express significant concerns – shared by business around the world –about the commercial environment in China – especially China’s lax intellectual property protection and enforcement, lack of transparency in government decision-making and numerous indigenous innovation policies that often preclude foreign companies from vying for Chinese government contracts. These policies mandate that products must be made, conceived and designed in China.

It’s important to note that since China formally joined the WTO nine years ago, it has made important progress opening its market. Tariffs have come down, private property rights are steadily evolving and great strides have been made to free the flow of commerce across China’s borders.

On balance, the competitive playing field in China is fairer to foreign firms that it was a decade ago. And we commend the Chinese for that.

It is also not lost on countries in the West that on our march towards industrialization, we sometimes protected native industries with policies that today would mobilize an army of WTO lawyers in opposition.

But those policies were folly then, and they are surely folly now. After World War II, the United States and a growing community of nations painstakingly built a global trading system based on the freer flow of goods, ideas and services across borders.

And the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995 ensured that countries would be held accountable for their commitments to open markets and lower barriers.

China has benefited tremendously from this international trading system, especially since it joined the WTO in 2001. The United States and other foreign nations have every right to seek more meaningful commitment and progress from China in implementing the market-opening policies it agreed to when it joined the WTO.

From our experience, there are usually five things that need to happen to turn these promises into reality.

It starts with the easiest step: a statement of principle from Chinese officials that action will be taken to solve a market access issue.

Next, that agreement has to be codified into binding law or regulations.

Third, the law or regulation needs to be faithfully implemented by the central government.

And fourth, it needs to be implemented at the local and provincial levels.

Only after all these things have happened can you arrive at the fifth, final and most important step, which is where this new law or regulation becomes a norm – an accepted way of doing business in China’s commercial culture.

When it comes to indigenous innovation, intellectual property or a variety of other market-access issues, an enduring frustration is that in too many cases only the earliest steps are taken, but not all five.

Perhaps an agreement is made, but it never becomes binding. Or perhaps there’s a well-written law or regulation at the national level, but there’s lax enforcement at the provincial or city level.

A few weeks ago, the Commerce Department and the office of the U.S. Trade Representative welcomed Vice Premier Wang Qishan and other leading Chinese officials for the 21st Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade, where we worked through a variety of specific trade issues.

It was a productive meeting. Vice Premier Wang and his team were responsive to our concerns and they pledged action in a variety of areas critical to American businesses.

They agreed to remove administrative and regulatory barriers discriminating against American companies selling everything from industrial machinery and telecom devices; to those that restrict U.S. participation in the development of large-scale wind farms in China.

They also agreed to revise one of their major government procurement catalogues to ensure a level playing field for foreign suppliers and to reduce the use of counterfeit software in government offices and state-owned enterprises.

Additionally, Vice Premier Wang asked the Commerce Department and the U.S. Trade Representative to partner with him on a public campaign to reduce intellectual property rights violations in China, which he is leading.

The American government welcomes these commitments from China.

But to be clear, they are only a first step. What was agreed to at the JCCT were important statements of principle and policy – but they must be turned into concrete action with results.

Take last year’s JCCT, when the Chinese agreed to remove a local content requirement for wind turbine suppliers – a positive step forward.

But soon after, China’s government employed a rule that required foreign businesses seeking to build large scale wind farms in China to have prior experience with such projects in China. The rule might have been different than the local content requirement, but it had the same effect – making it tougher for foreign companies to compete with China’s domestic companies.

At this year’s JCCT, we persuaded the Chinese to modify that rule as well.

Or look at the issue of intellectual property. We have heard Chinese leaders condemn IP-theft in the strongest terms, and we’ve seen central government laws and regulations written or amended to reflect that sentiment.

But American and other foreign companies, in industries ranging from pharmaceuticals and biotechnology to entertainment, still lose billions of dollars from counterfeiting and IP-theft in China every year.

For example, in the United States, for every $1 in computer hardware sales there is about 88 cents in software sales. But in China, for every dollar in hardware sales there is only eight cents in software sales.

According to the Business Software Alliance, that discrepancy is largely explained by the fact that nearly 80 percent of the software used on computers in China is counterfeit.

So America welcomes Vice Premier Wang’s pledge to accelerate China’s crackdown on intellectual property violations. And China will have a very willing partner in this endeavor in the United States. But we will be focused on meaningful outcomes.

I recognize I’m not the first foreign official to express concern over the commercial environment in China. But it would be a mistake to portray this concern solely as U.S. self-interest masquerading as advice.

The Chinese economy is increasingly moving up the global economic value chain, where growth is created not just by the power of a country’s industrial might, but also by the power of its people’s ideas and their inventions.

In the long run, economies with poor intellectual property protections and inconsistent application of market access laws will lose out on generating great new ideas and technologies. And they’ll lose out on the jobs that come with producing new products – jobs critical to an expanding middle class.

The damage won’t happen overnight. I freely admit that companies and countries can gain short-term advantages from lax rules in the commercial space.

But over time, if innovators fear that their inventions or ideas will be stolen or discriminated against, one of two things will happen – they’ll either stop inventing, or they’ll decide to create or sell their inventions elsewhere.

Ultimately, all that the United States seeks is a level playing field for its companies, where the cost and quality of their products determines whether or not they win business.

That is the ideal we strive for in the United States.

And our commitment to open and competitive markets is a big reason why we remain the number one destination for foreign direct investment in the world.

We understand that China’s modernization and evolution towards a more market-oriented economy is a process that will take time.

China has 1.3 billion people. Seven hundred million of them still live in rural areas; many with little electricity or running water. It took the United States over 100 years to build the electrical transmission capacity it has today.

To meet the rising demands of its own consumers, China will have to build a similar amount of capacity in just 15 years.

These are enormous undertakings. And it’s understandable if, in the past, China’s immediate development goals took precedence over other concerns.

With millions of Chinese coming in from the countryside looking for work, it isn’t necessarily an easy decision to close down a factory producing counterfeit goods, when that factory is providing badly needed jobs.

So what we’re discussing here are real and significant challenges. For market reforms to continue, it will take constant vigilance – not just from the United States, but from all countries and businesses around the world that benefit from rules-based trading. And from Chinese business and government leaders, who themselves have a strong stake in ensuring that China is friendly to global innovation and international competition.

In front of us is the opportunity for China and the United States to lead the world economy in the early 21st century to create a new foundation for sustainable growth for years to come.

We can’t tell exactly what that future will look like.

But we can be certain that it will be a better future if the Chinese and American governments pursue cooperation over confrontation in the economic sphere.

Cooperation that will put millions of our people to work.

Cooperation that will develop technologies to solve the most pressing environmental, economic and social challenges facing the world today.

This is the great opportunity before China and the United States. We just have to seize it.

Thank you.

###

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

appears that any agreements reached during December’s U.N. Conference on Climate Change will likely not include the two biggest emitters of greenhouse gases: the U.S. and China.

appears that any agreements reached during December’s U.N. Conference on Climate Change will likely not include the two biggest emitters of greenhouse gases: the U.S. and China.