Wang Nan’s Tian’anmen 26 Years Later

An early photo of Wang Nan, late 1980s

Wang Nan (pronounced Wong Nan) is a 45 year old Beijinger. Born in 1970, he has seen his city radically change under China’s economic miracle. In fact, as a photojournalist, he has documented China’s unfathomable rise and has been fortunate enough to partake in it. Wang Nan and his wife live more than comfortably in their renovated, Western-style apartment, where his photos from around the world line the walls. He knows he has been lucky, and he will tell you that immediately when you meet him; even with his world travels, he is still a fairly humble man. His 11-year-old daughter worships him even when he sings off key on their Sunday morning car rides to visit his mother. His 78-year-old mother, like all mothers, criticizes him as soon as he arrives – his hair is too long, he’s too skinny, he spoils his daughter – her granddaughter – too much. But like all mothers, she is proud of her son. And Sunday is her favorite day of the week.

But Wang Nan is not 45 years old. He has not shared in China’s economic miracle. He does not have a daughter. And he never sees his mother. For Wang Nan never made it past the age of 19. Instead, in the early morning hours of June 4, 1989, on the corner of Nancheng Street and Chang’an Boulevard – the Boulevard of Eternal Peace – a People’s Liberation Army’s bullet ripped through this high school student’s head.

As Louisa Lim recounts in her powerful book The People’s Republic of Amnesia, Wang Nan’s heart was still faintly

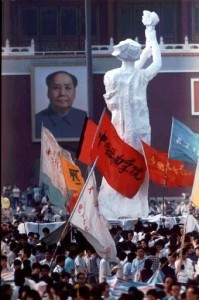

June 4, 1989, the aftermath of the Tian’anmen Crackdown

beating when doctors found him unconscious, bleeding from the head. They wanted to take him to the hospital, but the soldiers forbade it. Frantically, the doctors used their last bandage to cover his wound and stayed with him until he died two hours later. With the sun rising on that June 4 morning 26 years ago and desperate to hide the bodies, the soldiers dug a shallow grave in the lawn of the nearby school and dumped Wang Nan’s body there along with two other civilians. There it would lie until a few days later, when the stench was overwhelming and the dirt was beginning to wash away, the health department came to collect the bodies.

Wang Nan’s mother, Zhang Xianling (pronounced Zhang See-ann Ling), one of the founders of the Tian’anmen Mothers, has never been allowed to visit the spot where her son took his last breath. Every June 4, she is held under house arrest, with police standing guard at her apartment door, refusing to let her leave or for anyone else to come in. In a symbol of tormented anguish, she will communicate with the outside world on the anniversary of her son’s death by holding a photo of him out of her apartment window.

Zhang Xianling with a picture of her son, Wang Nan, killed on June 4, 1989

Twenty-six years later, as Lim poignantly recounts in her book, it is this impediment to remembrance and the Chinese Communist Party’s (“CCP”) complete control of the history surrounding June 4th that is perhaps the greatest tragedy of all. And as Lim points out, it is not just the parents who lost children that are not permitted to remember. Bao Tong (pronounced Bow (rhymes with pow) Tongue), director of China’s Office of Political Reform in 1989 and right-hand man to his mentor Zhao Ziyang, believed that Deng’s economic reform must be coupled with political reform, otherwise corruption would prevail. After the Tian’anmen crackdown, it was those thoughts that were blamed for the student protests and resulted in a seven year prison sentence for Bao. In 2005, when Zhao Ziyang passed away, the police, which constantly stand guard at his apartment, refused to let Bao attend the funeral. When his elderly wife attempted to go, the police pushed her to the ground, causing her to break a bone.

It is this recounting of the people’s history and the ghosts that still haunt them, that makes The People’s Republic of Amnesia one of the most important and moving books about the Tian’anmen crackdown. Lim also does an excellent and unbiased job of describing the precise events that lead up to the crackdown making the book a must read for anyone who wants to understand China’s history and the current leadership’s obsession with “social stability” and complete control.

But Lim not only tells the stories of those who witnessed the crackdown, but also those for whom June 4, 1989 has no significance, namely the babies born after 1990. In one study that Lim conducted, only 15 out of 100 Chinese college students were able to identify the infamous Tank Man photo, a photo that epitomizes the Tian’anmen crackdown and that is perhaps one of the world’s greatest symbols of courage. She follows a college student who goes to Hong Kong to try to understand Tian’anmen, but when he returns to China, he just seems confused and deflated. And then there is the Patriot, a Chinese car salesman who goes to Beijing to participate in the government-sponsored protests against the Japanese. Their failure and inability to know about the Tian’anmen crackdown demonstrates the true effectiveness of the CCP’s re-writing of the Chinese people’s history.

But Lim not only tells the stories of those who witnessed the crackdown, but also those for whom June 4, 1989 has no significance, namely the babies born after 1990. In one study that Lim conducted, only 15 out of 100 Chinese college students were able to identify the infamous Tank Man photo, a photo that epitomizes the Tian’anmen crackdown and that is perhaps one of the world’s greatest symbols of courage. She follows a college student who goes to Hong Kong to try to understand Tian’anmen, but when he returns to China, he just seems confused and deflated. And then there is the Patriot, a Chinese car salesman who goes to Beijing to participate in the government-sponsored protests against the Japanese. Their failure and inability to know about the Tian’anmen crackdown demonstrates the true effectiveness of the CCP’s re-writing of the Chinese people’s history.

Or does it? Yes, there is a generation of Chinese who have not heard of the Tian’anmen massacre. And then there are others who choose not to care. But to assume that the CCP can so easily erase this dark moment in China’s history is to deny the Chinese people their conscience. There is still a generation of Chinese – those born in the late 1960s and early 1970s – who know about Tian’anmen because they were alive when it happened. When this generation comes to power and can change the history, will they? Yes they might be busy making money now, but they have yet to ascend to leadership roles that would enable them to disclose the truth and recognize the bravery of those who died on June 4, 1989.

Tens of thousands march in Hong Kong last year to commemorate the 25th Anniversary of the Tian’anmen Massacre

There are the 11 Chinese college students, currently studying in various universities in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, who wrote an open letter to the Chinese people to communicate what happened on June 4, 1989. The government-controlled Global Times responded with an op-ed condemning these students. Like the students of 1989, these students have chosen to jeopardize their futures in China in an attempt to get the CCP to acknowledge June 4.

And then there are those – like the doctors who tried to help Wang Nan as he laid dying or the medical intern who, knowing the danger, gave Zhang Xianling her son’s last effects, or the individual who took out an ad in 2007 in a Chengdu newspaper stating “Paying tribute to the strong(-willed) mothers of June 4 victims” – who, when confronted with the choice, will do what is morally right, not what is politically expedient.

For these people, the world must continue to remember June 4, 1989, so that when the Chinese people themselves can commemorate this anniversary on their own terms, the memory will still be there.

Rating:

The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited

By Louisa Lim

(Oxford University Press, 2014)

211 pages

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email