Just For Fun: The Printed Image In China – 8th to 21st Century

For many, wood block prints are synonymous with all things Japanese. But as “The Printed Image in China” – a traveling show from the British Museum currently on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art – demonstrates, such a perception is totally wrong since it was China that first developed the technology, allowed it to flourish and made it an integral part of its culture and history. The Printed Image in China is a must see, but must be seen by the end of July before it closes on the 29th.

This small, six gallery show begins with the earliest known prints in the world. Although the Gutenberg Bible, printed in 1454, is commonly referred to as the first printed book, in reality, China was printing books, through wood block printing technology, as early as the 700s (likely even earlier). The Diamond Sutra, purchased by Hungarian-British explorer Marc Aurel Stein in 1907 from a monk in the Dunhuang region of China, is the earliest, dated printed book in the world, with a date of 868 A.D.

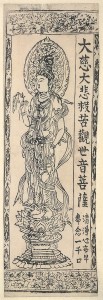

Although the Diamond Sutra is not part of the show, some of the thousands of other ancient manuscripts that were a part of Stein’s Dunhuang purchase and estimated to have been printed around the same time if not earlier, start this phenomenal show. For prints from the early Tang Dynasty (618 A.D. – 907 A.D.), the detail is truly astounding. In particular, “Bodhisattva Mahapratisara with the Text of ‘Da Sui qiu tuoluoni,‘” gives one pause, reciting an entire sutra within the print along with detailed pictures of Guanyin, making one wonder about the difficulty of carving it and the patience required.

The show then jumps to prints to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), where the technology of wood block truly began to thrive and the industry flourished. During the Ming, the use of multiple colors on a print – by carving different blocks for each color – developed, producing glorious prints that accurately copied the famous paintings of the day. Later on in the show an entire gallery – and a highlight – is dedicated to demonstrating the genius of this technique with actual replicas of the differently colored blocks that would be used to create a single picture. It’s easy to linger in that room, studying the intricacies of the method.

Wood block printing continued and peaked as an art form during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). By the middle Qing, wood block printing was

becoming its own art form. Whereas the goal of the Ming artists was to make the wood block prints appear as much as a painting as possible, the Qing artists began to experiment with more vibrant colors (think hot pink) and thinner paper which resulted in an embossed, tactile texture to the print, making it obvious this was not a painting. In addition, under the Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799), China experimented with the use of copper plates, prevalent in Europe at that time, Viewing some the etchings of famous European battles that the Jesuits priests brought with them to court, Emperor Qianlong (1711 – 1799) commissioned Matteo Ripa to create copper-plated etchings of Qianlong’s own battles.

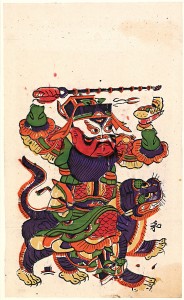

A high point of the show is the “folkloric” prints found in the third gallery. Unlike the pieces found in prior galleries, these prints – exploding with color – would have been everyday art, hung for New Years in an average person’s home. Depicting the doorway gods and the Kitchen God, these prints – dating to the mid to late 1800s – were likely purchased directly by British that were in China at the time and viewed them as art to be maintained. For the Chinese, these pictures were utilitarian in that they warded of the spirits for that year and, in keeping with tradition, would have been burned in preparation for the next New Year.

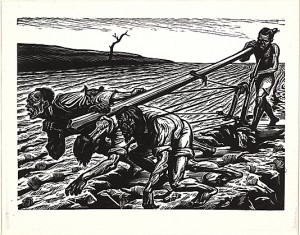

The final century, the 20th century, saw a renaissance of the wood block not just once but twice. With the fall of the Qing, the uncertain rule of the Nationalists and the impending invasion of the country by the Japanese, the average Chinese was suffering. Author Lu Xun (1881 – 1936), along with Li Shutong, were the major proponents of the “Modern Woodcut Movement” which used the sharpness of the woodcuts to reflect the harshness of daily existence in China. By the 1920s, woodcutting was on the rise throughout the world and would become a common medium for many artists attempting to depict and democratize the misery of the average individual. China was right along with Western nations in using the art form to communicate democratizing thoughts.

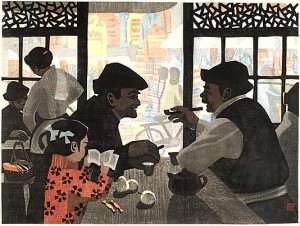

Wood block printing had a second 20th century renaissance under Chairman Mao Zedong (1949 – 1976). With the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the government became the only patron of the arts and art was there to only to serve the government. With the Communists, mass production became essential and where as in the past, wood carving was only one technique an artist might used, under the Mao, with its ability to create rapid reproductions for wide dissemination, wood carving would become a sole medium for many of the state-employed artists. As a result, a talented pool of woodcutters emerged, taking the skill of the craft to the next level; the artists were able to use the wood block prints to create a feel to the different materials and emotions depicted in the print.

With the death of Mao in 1976 and the re-emergence of the market economy, these artists have continued with their crafted, creating new wood blocks prints that express their own emotions instead of the Party line.

The Printed Imagine in China is a must see show before it closes on July 29 but not just for the astounding prints that fill every gallery in this show. What also emerges from this show and the careful way it has been laid out and described, is how this art form is an integral part of China’s political and cultural legacy and will be a part of its artistic future. From the first gallery, wood block prints were printed for political reasons –

with the Tang, the politics was religion. Spreading Buddhism was essential to the Tang Dynasty and the wood block prints, with its quicker way to reproduce the Buddha’s teaching, was important to that goal.

Under the Ming, spreading the literati culture became its own mission. Across the Empire, a cultural language arose amongst the elites – an educated man needed to have certain books on his shelves and certain paintings on his walls. Wood block printing created that mass culture among the literati. With the Qing dynasty, a foreign dynasty ruled by the Manchu people as opposed to the Han Chinese, wood block printing was used to solidify its rule, especially with the battle depictions of Emperor Qianlong. For much of the 20th Century, first under the Modern Woodcut Movement of Lu Xun and then the Communists of Mao Zedong, the political message was clear; under Mao, it was required.

Unlike the centuries before, the 21st century finds the art form – perhaps for the first time – unhinged from any political purpose. As the final gallery, with its post-1980s wood block prints, confirmed, the art form has exciting, new places to go that will do justice to its long history.

The Printed Image in China: 8th through 21st Century

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

(on loan from the British Museum)

1000 Fifth Ave (at 82nd Street)

New York, NY

Through July 29, 2012

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email

![nanjing[1]](https://chinalawandpolicy.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/nanjing1-206x300.jpg)