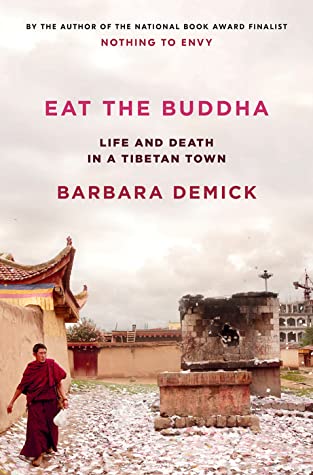

Book Review – Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in A Tibetan Town

Since 2017, the Chinese government has interred over a million Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, destroyed Uighur religious sites and limited – at times forcibly – the number of children a Uighur woman can have, all in what appears to be an effort to stamp out the Uighur culture. This summer, in Inner Mongolia, the government instituted policies that restrict the use of Mongolian in local schools, an effort Mongolian parents maintain is designed to eliminate their language and culture. For many outside of China, these policies are a shocking new development, reflective of the hardline approach of current President Xi Jinping. But, as Barbara Demick shows in her harrowing new book, Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in a Tibetan Town, for Tibetans, cultural destruction has been a part of their lives for the last 70 years.

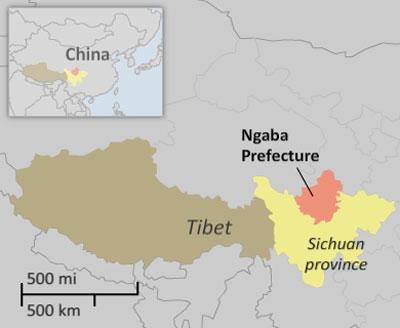

Eat the Buddha tells the story of this destruction by focusing on Ngaba, a town on the Tibetan plateau that has earned the morbid distinction as “the undisputed world capital of self-immolations.” Ngaba is not located in the Tibetan Special Autonomous Region (“SAR”), the area on a Chinese map that most non-Chinese think of as “Tibet.” Rather, Ngaba is located in the northwest region of China’s Sichuan province, and is an important reminder of just how far the Kingdom of Tibet once extended and how dispersed the Tibetan population is today. In fact, as Demick notes in her introduction, the vast majority of Tibetans in China live outside the Tibetan SAR, but this in no way lessens the Chinese government’s repressive rule. In many ways it is worse. According to the International Campaign for Tibet, since 2009, 45 Tibetans in Ngaba have self-immolated in protest. In Lhasa, the capital of the of Tibet SAR, only two have.

In Eat the Buddha, Demick asks why. Why have so many in Ngaba chosen to set themselves on fire, especially in a religion where suicide is not an accepted practice. Demick answer this question by examining the lives of eight Ngaba residents spread across generations, from the daughter of the last king of Ngaba (Princess Gonpo) to a twelve-year-old Tibetan girl, captivated by Chinese social media and uninterested in her own culture (Dechen). None of the people are particularly militant or even interested in Tibetan independence. Even Princess Gonpo, whose family members died, some by suspicious means, during the Cultural Revolution, is not anti-China and sees some of the benefits of being a part of the world’s second largest economy.

But as Demick tells their stories, each of the eight, even the younger ones, begin to resist Chinese rule and increasingly view the Chinese governments’ efforts in Ngaba as the degradation and ultimate destruction of their culture. And as Demick shows, these efforts have not just been limited to policies designed to “assimilate” the Tibetans; some have been violent attacks on the Tibetan people. Particularly harrowing is the retelling of the violence perpetuated on Delek’s grandparents in 1958 when he was just nine years old. As he hid in basket in their home, he heard screams and the senseless beating of his grandparents. When he emerged, this nine-year-old saw his grandmother, blood running down her head from where her braids had been ripped from her head. More recently, Ngaba has seen the increase militarization of the police force, creating an air of violence and captivity in the city, and at times resulting in the loss of innocent, young lives. For most of us who have studied Chinese history – at least those of us outside of the Mainland – we have been taught about the harshness of Chinese rule. But Eat the Buddha, by putting a personal face on this human suffering for the past 70 years, horrifies in the way a history lesson never can.

What Eat the Buddha also powerfully makes clear is that as much as the Chinese government attempts to censor this history in schools or tries to buy young Tibetan’s loyalty through a higher standard of living, these attempts ultimately fail. Dechen is a perfect example. When we first meet her, she is a twelve-year-old Tibetan girl fluent in Mandarin who loves watching Chinese movies that glorify the Chinese military. For her, Tibetan culture is for the old. But then, as Chinese rule becomes increasingly suffocating in Ngaba and her family members become victims of the government’s violence, she awakens her from her social media stupor.

By the time Demick reaches the start of self-immolation period in 2009, the reader is not shocked. It is the last form of protest available to Ngaba’s Tibetans, particularly the young monks at the Kirti monastery, grandchildren of those Tibetans first exposed to the Chinese government’s oppressive and violent rule. Unable to freely learn their religion and watching their culture be destroyed, they are left with nothing else but the ultimate sacrifice. The sad truth though, these self-immolations, with their shocking nature and international attention, result in the easing of some restrictions. 45 monks had to kill themselves in the most horrific of ways for the Chinese government to listen.

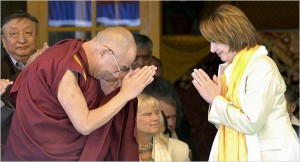

Eat the Buddha is a brilliant exposition of the Chinese efforts to eradicate a culture and how the culture pushes back. But that push-back is not enough to save the Tibetan culture and one starts to wonder why other countries aren’t doing more. Yes, some leaders, risking Beijing’s ire and meet with the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists (Angela Merkel in 2007; Barak Obama in 2016). But those are just symbolic gestures. And this is why Eat the Buddha is a must read. By telling Tibetan’s stories, Demick reminds us that the world’s commitment to human rights is more than just words, sometimes it is the difference between life and death for a people and their culture. Its time we give more than just words.

Rating:

Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in a Tibetan Town, by Barbara Demick (Penguin Random House, 2020), 352 pages.

Interested in purchasing the book? Considering supporting you local, independent bookstore. Find the nearest one here.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email