Bucking the system: China’s underground historians

In his new book Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future, veteran China reporter and author Ian Johnson introduces us to a cast of idealistic, charming and courageous characters who are trying to document China’s true history, in particular the stories of those who suffered under the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”). By countering the government-imposed, white-washed history, they go to the heart of the CCP’s legitimacy. The CCP calls them historical nihilists; Johnson just calls them underground historians. “China’s underground historians consciously aim for the masses. . . the goal is action – they are unapologetically activists who seek to change society,” Johnson writes in Sparks.

To understand more the role that underground historians currently play in China, China Law & Policy sat down with Ian to discuss the impact of their work in an increasingly surveilled society and with a leader even more hell-bent on maintaining CCP control of history. How are they able to get anything done, let alone change society?

Listen to our 44-minute interview by clicking the play button on the media player below. You can also read the transcript below the media player or download a PDF, timed-stamped version by clicking here.

Podcast Music: Clappy Hands by John Bartmann (intro); Outro Music: Motivational Day by AudioCoffee (outro)

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

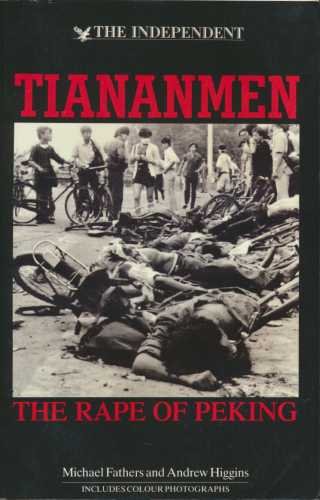

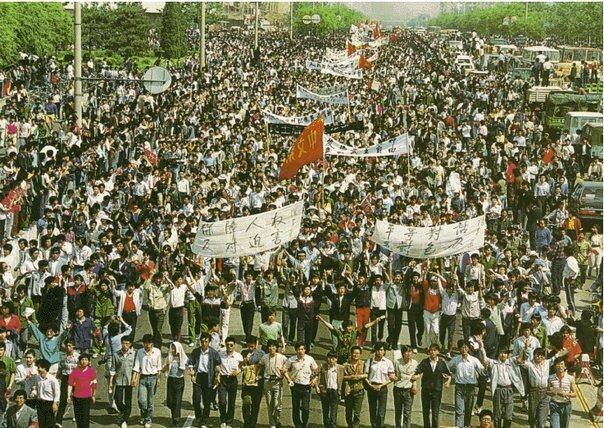

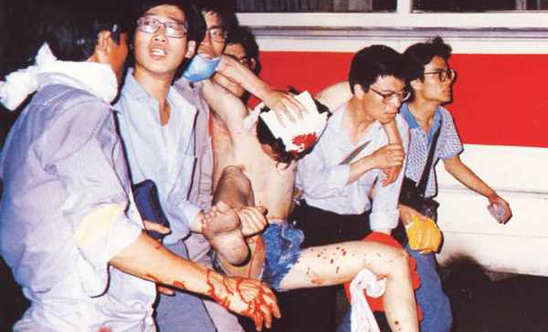

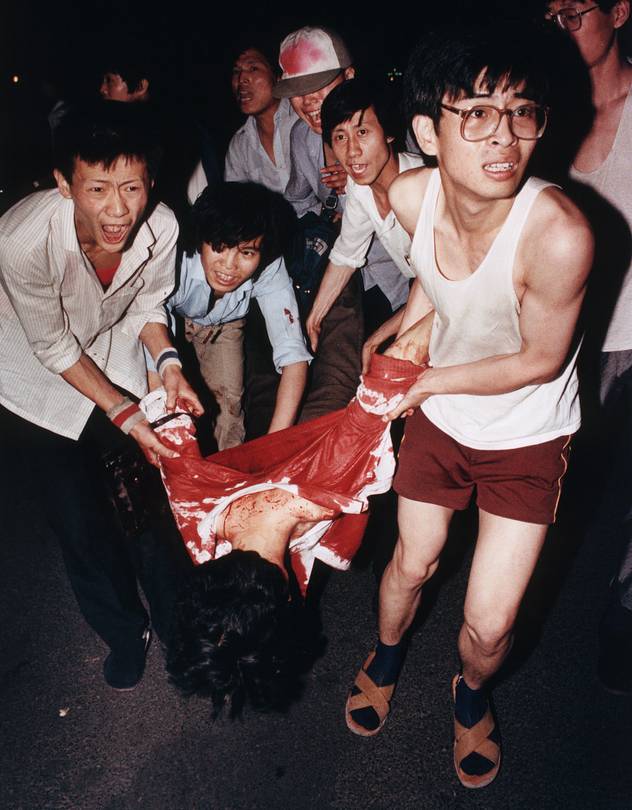

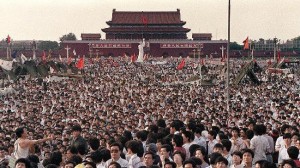

This is China Law & Policy, and welcome to our podcast. In any society history and how we choose to remember it is fraught. That is especially true in a country like China where the governing Chinese Communist party seeks to control the historical narrative in order to maintain its legitimacy. As a result, the CCP tries to erase from memory many of its most violent events, such as The Great Famine, the Tiananmen Massacre, and increasingly the cultural revolution.

But has the CCP succeeded? Ian Johnson and his new book Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and their Battle for the Future shows that there’s a grassroots movement underway to counter the CCPs historical narrative and remember these events. Even in a country with increasingly tight surveillance, these stories are getting through.

Ian joins us today to talk about his book Sparks and the efforts to preserve an accurate account of China’s history. Ian is a veteran China reporter and author who lived in China for over 20 years, and in 2001 won the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the Chinese government suppression of Falun Gong practitioners. He’s currently the senior fellow for China Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

CL&P: Ian, thank you for joining us today.

Johnson: It’s my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

CL&P: So just to start off, who are these underground historians? How do you define them and what is their importance to China?

Johnson: The term underground historians is a compromise. Some people will say, are they PhD historians who teach at universities, as we might think a historian to be? I use the term very broadly for anybody who is writing history in any way or making a documentary film about it–bloggers and journalists, essayists, and sometimes even novelists who are using historical fiction to challenge the party. So in this sense, it’s more analogous perhaps to how we in the West might think of popular history or grassroots history, that sort of thing. I say underground also to avoid the word dissident, which is a somewhat of a fraught term because these [people I write about] are not people who are holed up in their basement. They often have one foot inside the system and one foot outside the system. They might be professors at a university or hold some kind of other regular job, own property, send their kids to college and stuff like that. But they felt a calling to explore an aspect of Chinese history that they feel is being whitewashed and they publicized it as best as they can.

CL&P: Now, would you characterize any of them as dissidents?

Johnson: It’s a spectrum, and some of them are dissidents for sure. If he were still alive, the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Liu Xiaobo could be included because of how he has looked and investigated parts of Chinese history. Some of them face harassment by the government, if that makes them a dissident or not it’s hard to say. I think the government is pushing a lot of people into the dissident category who in the past weren’t. I can give you an example: the novelist, Fang Fang, a pseudonym for a writer in Wuhan called Wang Fang. In the West she is best known for her Wuhan Diary that chronicled the roughly 60 days in 2020 when the virus erupted in Wuhan and the truly traumatic and draconian lockdown of that city.

In the past, she was a government-approved writer. She was head of the Writer’s Association in Wuhan and in the province of Hubei, which is a huge inland province of China on the Yangzi River. She was an establishment person whose books are published in China, and she wrote mainly about working class people and so on and so forth–things that were not far from the government’s interests as a communist party, let’s say. But over the past few years, even predating the Diary, in the late 2010s, I think it was 2018 or 2019, she began to tackle sensitive issues. One was on the campaign against the so-called landlords in the late forties and early fifties, which eliminated the gentry in China and paved the way for Party rule over local society, especially in the countryside. She wrote this book called Soft Burial, and that book at first was published in Beijing by an official publishing house.

And then I think the party realized, wait a minute, this is an area that’s super sensitive, we can’t allow this. The campaign against the landlords is in some ways the original sin of the PRC. And so they banned the book and then she lost her position as head of the Writer’s Association. She’s been pushed progressively into this dissident role. By the way, that book is going to be published in English in the autumn by Columbia University Press, translated by the well-known translator, Michael Berry from UCLA along with another novel of hers. So that’s something for people to watch out for in I think September of 2024.

CL&P: And when did things change for her with Soft Burial? You said that it was originally able to be published and now it’s been banned. When did that ban happen approximately?

Johnson: It happened pretty quickly after it was published. I’m going to say it was 2019. I think the situation for people investigating the past has gotten worse over the 2010s progressively. It’s been a bit like the proverbial frog and the pot of hot water that’s getting hotter and hotter and doesn’t realize it. You can’t say the light switch suddenly flipped. I think it’s simplistic to say it all started with Xi Jinping taking power. Certainly as with a lot of things, he supercharged these trends that had been there earlier. If you want to think of a turning point, it really probably was around 2018 when he made clear that he was going to change the constitution to allow a third term, which was not allowed. It wasn’t some ancient tradition, but there had been this accepted norm of only having two terms for a top leader. He made clear in 2018 that wasn’t going to be the case, and that in 2022 he was going to take a third term, which is indeed what happened in 2022.

CL&P: I guess in that regards, when I read Sparks, you talked about how the CCP needs to control this history and to whitewash some of the worst parts of its history to maintain its legitimacy. But do you actually think that is necessary to maintain its legitimacy? Because in the 1980s, 1990s, you did have a lot of the memoirs about the Cultural Revolution where people wrote about a lot of the horrible things that happened and it didn’t topple the CCP. I mean, in your mind, is there a need to really whitewash this? Would this topple the CCP if a lot of this came out more?

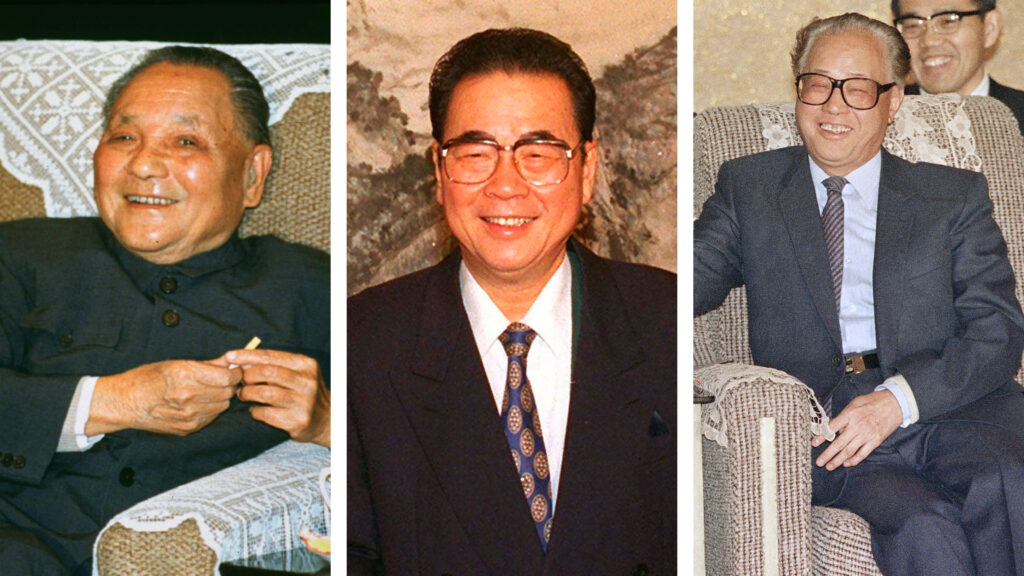

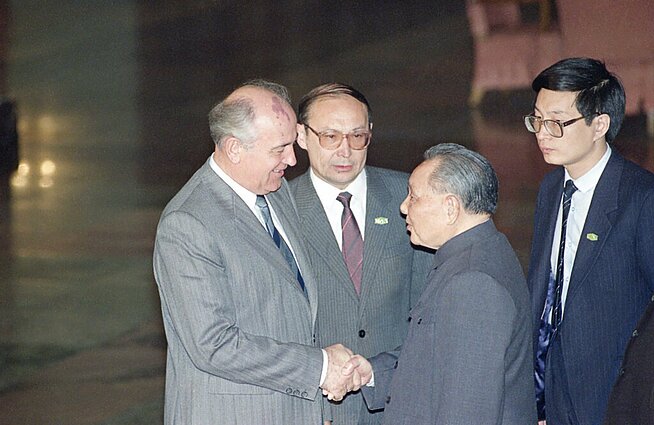

Johnson: I don’t think it would topple the CCP. If you suddenly had freedom of the press and people could publish whatever they wanted, you might also find some people who are radical supporters of the CCP or super nationalists who are even more nationalistic than what’s allowed today. And yet freedom of the press could still contribute to the undermining of the Party. And I think that’s certainly what Xi Jinping thinks because one of his signature policies, if you look back over the 12 years that he’s been in power has been control of history. He has explicitly said that one of the key reasons for the fall of the Soviet Union was the ideological hollowing out of the project of communism. Gorbachev launched two initiatives, Perestroika and Glasnost: economic reconstruction and openness.

The [Chinese Communist] Party embraced the idea of economic reconstruction, so after the Soviet Union collapsed, Deng supercharged the economic reforms through the 1990s. He and his handpicked successors pushed for a more open market-based economy, thinking that a high standard of living would satiate most people’s desire for change. I don’t think Xi Jinping’s turned his back on that entirely, but he said the other problem, the key problem of Gorbachev and the Soviet Union was Glasnost. It was too much openness and that this caused the hollowing out of the Soviet Union. He [Xi] has a line in one of his speeches where he says no one was “man enough” to stop this ridiculous effort to disband the Soviet Union–and we’re not going to allow that to happen in China. So we have to reassert control. From this you can see that he sees it (control of history) as a key issue. People sometimes have this idea that authoritarian leaders are omnipotent, but they actually have a limited amount of political capital that they can expand on any one issue, just like any politician anywhere. And so he chose to go after this because he thinks it’s important. Now maybe he’s wrong, but that’s at least what he thinks.

CL&P: In terms of the government’s approach, the Chinese government’s approach to history. I do want to ask you about historian’s access to the Chinese government’s archives. So I think in Sparks or maybe in another interview you mentioned Yang Jisheng‘s book Tombstone, which used the government archives to see how bad things got during the Great Famine where 35 to 45 million Chinese people starved [to death]. And I think the same has happened with the Culture Revolution. There was a little bit of opening in the late nineties of the archives about what the government was thinking, but my understanding is that those archives have largely closed. And I guess can you just give some of the background on that, the time period, why did it open? Why was it seen as good to open them? And then when around did it close? And what’s the impact of the closing of the archives on these underground historians, if any?

Johnson: It’s hard to know exactly when the archives opened, but there was a possibility in the eighties and nineties, especially up into the two thousands to go into some parts of the archives. Yang Jisheng, when he was researching Tombstone, didn’t look in the Public Security Bureau files or something [sensitive] like that. He looked in mostly the Ministry or the Department of Agriculture files. And there he could find lots of statistics and information because often documents get cross filed. And of course you can think of famine that was mainly caused by agricultural policies, you’d find stuff there. He was able to mine those archives. So was Frank Dikötter in his book, China’s Great Famine or Mao’s Great Famine. Those two landmark works rely heavily on archives. Starting in the two thousands, the government began to realize that this was happening and began to close down access to archives.

So Yang Jisheng, for example, has not been able to access the archives in I’d say at least 20 years. And so that’s in fact why in Sparks, I don’t look at those historians so much. Yang is an important figure, a key figure in the movement early on. But I’m trying to see people who are active in China today.

I think the archives, this is across the board, you can talk to academics almost any topic, it’s almost impossible to get access to almost anything you can imagine. Even the Republican era or the Qing era, everything’s becoming more and more sensitive because of how it might be interpreted.

CL&P: And you said that they started closing the archives in the early two thousands. So this is even before Xi Jinping?

Johnson: Yes. That’s why I think it’s important to see these trends, not just for these underground historians, but if we’re looking more broadly at trends in civil society, that the tide had turned before he took power. Certainly by the Olympics, things had changed. If you want to see a symbolic turning point, it might be the arrest of Liu Xiaobo at the end of ’08. Clearly by then the government had made a decision that dissent in any form was a problem. It went after social media. Weibo was basically knee-capped in about 2010. They got rid of the big influencers on Weibo called the Big Vs, the verified accounts. These were big public figures who had sometimes millions of followers. They sanitized Weibo and pushed people onto WeChat and then sanitized WeChat. All of this predated Xi Jinping taking power. I think as in other areas, he supercharged this. He’s a more forceful leader who has more levers of power, has less opposition, and so could ram through these changes more forcefully than his predecessors.

CL&P: And I guess if these archives are now being closed, why doesn’t the Chinese government just destroy the archives? Do you think that would ever happen?

Johnson: It’s possible. It’s hard to know since we don’t have access to it. There’s a book by the British spy novelist Robert Harris called Fatherland. In it, he posits that the Nazis won World War II and destroyed all the evidence of the Holocaust. There were just a few people fighting in the Ural Mountains. There were rumors that there’d been this destruction of European Jewry, but nobody could actually prove it. Something similar could happen in China. The longer the Party stays in power, the more things will get sanitized. When things do come out of an authoritarian state, it often is during a period of crisis. What happened, for example, in East Germany was a once in a millennium event where an authoritarian state was toppled in a really short time.

The Stasi headquarters was overrun by citizen activists in ’89. They [the Stasi] were shredding paper. But the citizens got there before most of the stuff was shredded. And so that’s why they have this amazing resource, the Stasi archives in Berlin today. But that kind of thing was the exception. And the same with the Soviet archives. The Soviet archives were open for a few years in the early nineties, but by the end of the Yeltsin era was closed off. It was the same thing with the CCP. We have access to some stuff because of the turmoil at the end of the Cultural Revolution and the beginning of the Reform Era when the government tried to make amends.

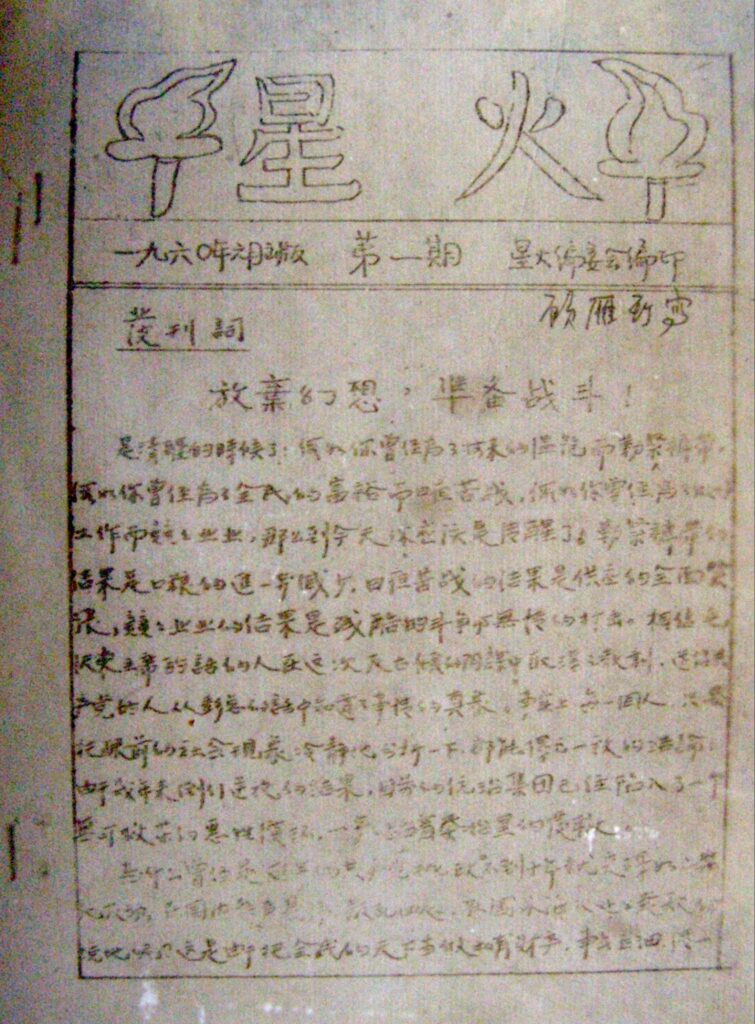

This is a brief period under the former party Secretary Hu Yaobang in the early to mid-eighties when they tried to make amends for the events of the Mao era. I think we sometimes overemphasized the Cultural Revolution. It wasn’t just the Cultural Revolution, the whole Mao Era, the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Famine and so on. And so the archives and personal documents, personal files were made available to people. That’s why this magazine that I write about in the book, Spark, that’s why we even know about it because of that movement. So during those kinds of turmoil or upheaval, stuff will erupt from an authoritarian state. But if the authoritarian state can reassert control, such as happened in post-Soviet Russia under Putin or happened in post-Mao China, eventually then the archives disappear and are closed off again.

CL&P: In Sparks, you do seem to have a lot of hope for today’s underground historians, but as you’ve shown in your book, there have been others in the past that have attempted to counter the CCP’s official narrative, like the young people who drafted Spark, and their fate has often been prison or even execution. I guess why do you have more hope for the underground historians today than the people in the past?

Johnson: I don’t have hope that they’re going to become the Václav Havels of tomorrow and end up running China. But I think the human spirit is harder to crush than sometimes people imagine. I think China is also a messier place than we sometimes think. You can create a scenario, involving AI, facial recognition software and other things where China becomes a perfect dictatorship where nobody can do anything–they’re monitored the whole time. That could be the case in the future, this Orwellian or Aldous Huxley type idea of China. But if you actually go to China, on the ground things are a lot messier. It’s not carried out to quite the same extent, and at least for now. When I went back there last year, many of the people I wrote about in the book are still active.

And so I think it’s not true that there is nobody doing anything in China. Some of the people, as I said that I write about, the underground filmmakers are still making films. The history journals like Remembrance are still being published. But it’s true that people have limited goals. Many of people working in this tend to see themselves as patriots who are trying to get on record as much as they can now for future generations. It’s a bit like a message in a bottle that they hope somebody will be able to find and read somewhere. That’s why they don’t feel defeated by the fact that, for example, when they make a film, they have to put it on YouTube and that most Chinese people won’t be able to see it [editor’s note: YouTube is blocked in China.]. They feel at least that way it’s preserved somewhere, it’s kept alive, and in the future, Chinese people, hopefully one day down the road, will be able to make use of this material.

CL&P: And in talking about the future Chinese generations, most of the historians that you feature, the underground historians you feature in your book, it seems like almost all of them are above the age of 50, maybe Jiang Xue is maybe a little bit younger. But I guess for younger generations, do you see the underground history movement continuing? Do you think there will be the same kind of interest in uncovering these issues for the younger generation that’s more online, that’s less in touch with the past with people from the Cultural Revolution or the Great Leap Forward or even Land Reform?

Johnson: Yeah, I do think so. I think it depends of course on China’s trajectory. If you think of young people in China, say young in the sense of maybe anybody under 40, until recently, they haven’t experienced a major trauma in their life. Perhaps if they were involved with Falun Gong, they might have. Of course, if they were Uyghurs they might have. But for the vast majority of people who are say 35, 40 years old, they probably don’t have any memory of Tiananmen. The nineties, two thousands, and most of the 2010s were a period of unprecedented economic growth averaging 9% a year over that period. Tomorrow was a better day, society might have a lot of problems, but if you kept your head down, you could go about constructing a comfortable life for yourself. You could follow hobbies; you could even explore some elements of the past.

But over the past few years that has changed. For the more politically-aware people, that might’ve started in 2018 when Xi signaled that he was taking a third term. That was a shock for many people that he was going to be there forever. We were sort of back to the Mao era when leaders just died in the saddle apparently and never stepped down. That was a shock. But certainly for many more people, the handling of the Covid situation was a turning point. Initially, I wrote a piece for the New York Review of Books in late 2020 called “How Did China Beat Its COVID Crisis?” It is kind of funny now to look at it, but at the time, it seemed like China had. They had a harsh lockdown in Wuhan but they were able to then reopen the country by May of 2020. And it seemed like they’d created an island of COVID-free life for 1.4 billion people.

So the lockdowns worked initially. But by 2021, that no longer worked, especially with the Omicron variant. The lockdowns were getting harsher and harsher. The economy was slowing. People began to wonder, is this government as technocratic as we thought, is this social contract of ‘you’ll leave us alone as long as we don’t touch elite politics,’ is that still in place? And I think we saw the answer for a lot of people was “no.” In 2022, the Shanghai lockdowns, the White Paper Protests, these were not huge events, we shouldn’t exaggerate them, but they were significant. They were the biggest widespread protests in decades. So these events represented, for young people a bit of a shock to the system. And that’s why you see there are young people who are now writing about these events. There’s a filmmaker, Chen Pinlin, who made a film about the lockdown called Not the Foreign Force. Foreign force is a term that the CCP uses to say that it’s outsiders who are fomenting troubles – jingwai shili (境外势力). And she says that it is not the case. It is the story of the Shanghai lockdowns and how it spread because of the government’s heavy handed policies. So I do think you see young people writing about this.

It’s similar for other generations. For elderly people, it might’ve been that they personally experienced the Anti-Rightist Campaign or the Great Famine or the Cultural Revolution. Or if you’re middle aged, it might’ve been Tiananmen, but it probably is something that you experienced firsthand.

So it’s not surprising to me that there were not, until recently, that many thirty-something year olds doing that. But now we’re seeing people in the 20- 30-year age bracket who are getting involved because reaction to the government’s policies. But if the government turns things around, if we go back to strong economic growth, and if they lighten up a little bit on the heavy handed social controls and let people live their life a little bit more, you may find that these people are not as relevant as I’m thinking they may become. But if you look at Xi Jinping, who seems to be an ossified figure who is not able to course correct, I do wonder where China will be in 10 years from now. And if they don’t course correct, you’ll have probably all of these social problems that we have today, high youth unemployment, China maybe not making it into the ranks of the developed countries –then that could cause social problems down the road. And that will fuel people who are offering alternative explanations of reality, which is essentially what these underground historians offer.

CL&P: And just to focus again on what the underground historians that you covered are looking at vis-a-vis other incidents in the CCP’s history, most of the events that they are looking at for the underground historians in your book, they’re looking at things before the 1980s, before Reform and Opening. And I did find it interesting that you had no analysis of any historians looking at Tiananmen and the 1989 crackdown and massacre in Tiananmen. And I guess is that because there’s nobody out there. . . that is way too political that nobody can touch it in China, or was it just you didn’t find anybody to cover for that? I guess the absence of Tiananmen and analysis of that by underground historians was interesting to me.

Johnson: That’s a good point. It was something that I didn’t think about when I was initially doing researching and writing the book. But as I had a first draft, I thought, there’s not much on Tiananmen. Then I realized that I think the reason is that I wanted to focus on people who are doing things inside China today. And it seems like most of the research on that is overseas. And so I didn’t want to write about exiles and overseas dissidents. There’s a lot of great research that’s been done on Tiananmen, and certainly it’s something that I include. I’ve created this thing called the China Unofficial Archive, which makes available online the amazing output of these unofficial historians in China. And we do have material on Tiananmen. It’s [the website] still in its infancy, but we are putting more and more stuff on Tiananmen up.

So that was one reason. But also the Mao Era was a crisis for China that impacts people today. In some ways it symbolizes even for young people what went wrong. It was when China really went down a path from which it hasn’t recovered. You can think of the Reform Era as a desperate effort to use economic growth to pave over the destruction caused by the Mao Era. One of the people I write about in the book, and I’m writing a profile on now in a little bit more in depth, is Gao Er’tai. Gao Er’tai wrote a book called In Search of My Homeland, which is a series of essays about the Great Famine, and the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Cultural Revolution. He now lives in the United States and is 88 years old.

I encountered him online during the COVID lockdowns. His essays were being recirculated on social media. The camp that he writes about was called Jiabiangou. Jiabiangou has become a synonym, a slang term on the web in China, for “the Gulag.” Young people tell me that they even say, ‘watch out, or they’ll send you to Jiabiangou.’ Jiabiangou was closed down in about 1960, this era still resonates today in ways that maybe Tiananmen don’t quite resonate. And I think for young people Tiananmen, I have to be a little bit careful on how I put this, but some of the exile groups that have been most associated with Tiananmen have been involved in a lot of political infighting.

They’ve gotten caught up in the #MeToo movement. They seem to a lot of young people like typical exile groups throughout history that are squabbling more internally than addressing future issues. That’s not entirely fair, but I think maybe that’s why that particular crisis [Tiananmen] for young people today maybe doesn’t seem quite as relevant in assessing China as the Mao era, where the roots of today’s problems were laid.

CL&P: But to go back to something you just said about the Jiabiangou, the labor camp during the Anti-Rightist movement. So in reading your book, that was the first I heard about it. I don’t think there is a lot of focus on what happened during the Anti-Rightist Campaign. And you said that young people use that sort of to refer as in America where we talk about the Gulag. Is that a new development in bringing that into the vocabulary, or has it always been sort of known about Jiabiangou?

Johnson: It wasn’t that well known until the rise of the unofficial history movement in the late nineties and early two thousands. It entered the public consciousness first due to a Shanghai-based writer named Yang Xianhui. Yang wrote a series of vignettes translated as Woman From Shanghai that were based directly on oral histories that he conducted with people. His middle school teacher disappeared and died in Jiabiangou. He fictionalized the stories but they were basically true stories. Then the Paris-based, filmmaker Wang Bing made a film called “The Ditch” based on one of Yang’s stories.

Wang Bing also did a purely art film called Traces, where he walks around the desert with his camera. It’s very abstract– a video installation. But I think Wang is probably a little better known than Ai Xiaoming, who’s one of the main characters in my book. She made a film called Jiabiangou [Elegy], which is an incredibly ambitious four and a half hour film influenced heavily by Shoah and other Holocaust films. Ai is an autodidactic filmmaker, but a very serious filmmaker who’s looked at all these great films about the Holocaust. Hu Jie, probably the best known independent filmmaker inside China still working, also made a couple of films about this same material. He made a film called Spark, about the Lanzhou student movement.

He also made a film called In Search of Lin Zhao’s Soul, which was also touched on that material. Through these works Jiabiangou and the events of that time became better known. And then Gao Er’tai’s memoirs, which were first published in 2004, and then an expanded form in 2009 began to spread. They became popular in social media because they’re written as a series of vignettes. They’re about 62 kind of standalone essays. They’re interlinked chronologically, but you can just carve out one and put it online as a 3,000, 4,000 word piece. They became really popular during the lockdown. I don’t have systematic proof of that, but this is certainly based on what other people tell me. On social media feeds, there is a bit of an echo chamber, I realize that, but it seemed like it was pretty popular because it explained the absurdity of CCP rule, the heavy handedness of CCP rule, the arbitrariness of one-man rule and things like that–the Mao Era having a direct resonance today in the Xi Era. Again, I think maybe why the Mao Era resonates more than say Tiananmen.

CL&P: And just in looking at the events that you cover, that the underground historians investigate in your book, I mean they are some of the most horrific and shameful parts of Chinese history. And given that your book is for a general audience, not just for a China-based audience, are you worried that people who aren’t as familiar with Chinese history and Chinese culture when they finish the book, might think that China’s uniquely troubled? And I bring this up because the Three Body Problem on Netflix is being shown, and I know I have a lot of friends and colleagues who’ve asked me about the struggle session that opens that series. And there does seem to be questions that seem to come from a place where this is a uniquely Chinese thing, the horribleness that people can treat each other. I guess, were you worried about that at all in focusing on these events?

Johnson: Yes, I do mention in the introduction, and then especially in the conclusion, I say, rather than seeing them as uniquely Chinese, we should see them as part of a global conversation about how we deal with the past. And that rather than seeing people like Fang Fang as a one-off author in this far away land–“planet China”–that has these weird things going on, we should see her as part of our cultural heritage. She uses techniques of historical-based fiction used by U.S. superstar academic writers like Saidiya Hartman at Columbia University. She uses fiction to recreate the enslaved person’s experiences because we don’t obviously have memoirs and diaries of enslaved people. So she does all the research possible, and then she uses a bit of imagination to put herself in that person’s place and writes about what it might’ve been like to come over on a slave ship.

This is in the conclusion, I issue a plea for civil society in the West to try to bring these people more into our conversations. We don’t translate their works enough. Thank goodness that Fang Fang’s novels are now being translated a little bit. But when I think back to the Cold War, people like Václav Havel and Milos Forman and Milan Kundera were kind of household names among educated people in the West in a way that their Chinese counterparts today are not. We need to find a way to get these works published, get the movies out there, have a festival for some of the films. And that’s why I hope it can become part of our world and not just some weird thing off in China.

CL&P: Yeah. And why do you think it’s not part of our world? Is it a language or cultural issue, right? You talked about the Cold War, there were more translations going on. Is it a lack of funding? I mean, why do you think it’s not being brought into the Western canon as much?

Johnson: There’s a bunch of reasons, and I’ll mention a few, in no particular order. But I think one, for example, is publishing. I remember in the 1980s, Philip Roth wrote a series of introductions for Central European authors, and they were published by a mainstream publisher [Penguin]. But publishers today are under much more commercial pressure, so that if you’re an editor, you can’t just say, “hey, you know what? I’m just going to publish this stuff because I know it’s not going to make any money, but I feel that this is an important thing. I am going to commission the translation, and we may lose money, but we’re going to make a ton of money elsewhere.” And now when you go to Amazon, you see hardcover books that list for $25 being sold for $19. That $5 is a big chunk of the profit margin of the publishers. So they have to look really carefully at what they publish. This is part of the digitization and the way you can compartmentalize financial returns on things that affect the media in general, newspapers and so on. So there’s that reason.

But also China for many people feels further away. Central Europe was part of the West, so to speak, or you could see them as part of the West, especially Czechoslovakia and Poland and even Russia. Solzhenitsyn wrote in a format–the Russian novel–that was familiar to educated people in the West.

Language is [also] a problem. When they do get overseas, if you were to invite some people over, they don’t speak English. By and large, almost none of the people I write about in the book speak English. People like Ai Weiwei is the total outlier. That’s why he gets so much media attention, because he can speak great English. For example I was trying to get a prominent Chinese journalist a fellowship at a major university here in the West, and they said, well, ‘how’s she going to participate in the fellowship if she can’t speak English very well?’

Finally, there’s a fatalism toward China. We have this idea, we’ve written off China in a way. We’ve just decided we’ve got to decouple from China. Nothing’s happening in China. We need to protect ourselves from China. Basically there’s nothing good happening there. And that’s why I think so few people go and study China. So few young people are excited by going to China or wanting to do that, which I think is a real pity because we have a huge chunk of humanity that we’re just writing off.

CL&P: And I think the underground historians you feature, you really humanize them and they sound like fun, quirky people that are doing really good work. And one of the things I did notice, and you do write about this in Sparks, is two of the recurring characters, Jiang Xue and Ai Xiaoming, and then also Fang Fang, who you mention a lot, they’re women. And I think in a lot of movements in China, you don’t see women featured as much. I mean, I do think that is changing. The feminist movement in China, or at least now outside of China is very strong. But I guess why are you seeing more women in this movement and how are women treated in this movement by their male colleagues? Is their scholarship treated as on par with theirs, or is there any kind of negative gender dynamics?

Johnson: I didn’t set out to have two women as my main characters, but that’s essentially what my reporting found. And obviously there’s some path dependency when you’re doing research like this. But I do think that a disproportionate number of women are involved. Sometimes when you get men involved in these kind of situations, the male ego, the testosterone, gets involved. It tends to be very confrontational: it’s me against the goddamn system kind of thing. Whereas women tend to, here, I’m stereotyping massively, but maybe women sometimes just set about doing stuff and actually creating things, creating networks, creating works. Perhaps that’s one reason for it.

But also, women are outsiders in Chinese society. Chinese politics is run by men. There are almost no women. There are no women in the Standing Committee of the Politburo. I don’t think there’s any woman in the Politburo now for the first time in decades. So if you’re a woman, you are from the beginning an outsider. It’s similar perhaps to Jews in European society last century, where they were part of the society, but were always outsiders. That gave Jewish people a bit of a different view of things. And that’s often the interesting view. If you’re too much inside the system, you can’t describe it so well. If you have a little bit of an angle, if you’re isolated, if you’re marginalized to some degree, then you do have a more critical analytical and maybe objective way of looking at society. I think that’s what women bring to the table.

CL&P: And I see we’re running short on time. I just wanted to switch gears a bit. You had mentioned the China Unofficial Archives website that you’ve started. Can you just briefly talk about that? Is it accessible in China and what’s the goal of that website? And maybe even give the website name, which I will also put in the transcript.

Johnson: Yeah. It’s called the China Unofficial Archives or in Chinese, it’s the Mianjian Dang’an Guan (民间档案馆). The URL is actually the pinyin of that, which you could put in. . .

CL&P: Yeah, I’ll put in the transcript [https://minjian-danganguan.org/].

Johnson: We’re a 501(c)(3)-registered charitable organization in the US. It was set up for a couple of reasons. The main reason was to make available just all of this material in one site. People often ask me, Hey, where can I read this stuff? Where can I find out more about this? At the end of my book, I have some suggested readings. I was just building the site at that time, and I didn’t maybe emphasize it enough. But that is where you can find all the people I write about in the book, and many, many, many more. It’s still in its infancy. We have 850 items in the archive. They’re sortable by era format, creator and theme. So if you want say, films on the Cultural Revolution, you can click on format: film and era: Cultural Revolution, and it’ll quickly sort and give you the films we have. We’re just digitizing another 125 films and putting them up on the site. We also offer downloadable PDFs of public-domain books and magazines.

The main audience is Chinese people, but the site is fully bilingual. We have descriptions in English and in Chinese. But I think of it as serving people who might be interested in this topic in China or abroad who don’t have access to a major research library. It’s not available in China, it was very quickly blocked because there are these search bots that just find words like Cultural Revolution, so on. It was immediately blocked once we went live in December of last year.

But I think that’s okay because the people who are most active have VPNs and they also act as gatekeepers. They can download the PDFs of these books and magazines and spread them inside China. So that’s the basic game plan. I think also, maybe the 20% or 10% of my idea was also to show people in the West that there are more writers and directors than they think. It’s not just a few dissidents doing this. It’s actually a lot of people in many different parts of China who are working on these things. I want to destroy the idea that it’s just a few dissidents in Beijing or Shanghai or some places like that who are active. It’s actually a broad based movement. We’re going to be moving to a new data management system, which will allow us to do data visualization so we can see where the people are, where the works are on a map of China, and you can isolate that and work with that.

CL&P: Okay, cool. No, I’ve looked at the website and it’s super cool, and I’m really excited to see it moving forward and everything. So yeah, so I think that’s everything for today. I really appreciate you taking the time to speak to us today. I thought Sparks was really a great book, and I do highly recommend it to other people to not just learn about Chinese history, but to also learn about these amazing people who are trying to preserve Chinese history, the accurate Chinese history for future generations. So thank you, Ian.

Johnson: My pleasure. Thank you.

On Facebook

On Facebook By Email

By Email